3D Printing in the Classroom: Course Assignments and the Makerspace

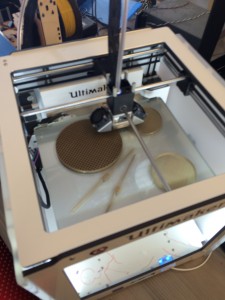

During the first week of the spring semester, the Makerspace was a flurry of activity, our Ultimaker 2 printing feverishly throughout the day. Groups of students came in and out, selecting and slicing models, checking on their 3D prints, and assembling different components. This week marked the beginning of a new semester-long assignment created by Slavic Librarian Kathleen Thompson, Slavic Lecturer Jill Martiniuk, and myself to better integrate 3D fabrication and physical computing resources in the classroom. After months of discussing course objectives and possible digital components, including website creation, Arduino programming, and 3D printing, Kathleen and Jill determined that 3D printing would allow students to engage physically with ‘icons’ of Russian identity for Yuri Urbanovich’s ‘Understanding Russia: Symbols, Myths, and Archetypes of Identity’ course and to think critically about how such icons are made, circulated, and contextualized/decontextualized.

Logistically, this assignment only required that we block off enough time for the students to stop by and print their selected models (mostly selected from Thingiverse). Most the students had never been to the Makerspace before and this offered a great opportunity to introduce the equipment and resources to a new audience. It was clear that the process and time required to make these objects encouraged the students to think critically about their objects, with some questioning whether or not an object was “too negative” or even if certain models they selected would print properly. The students were able to control various aspects of their prints, including filament color, print scale, and assembly options, and many students took this opportunity to think symbolically about what and how their object communicated. As students have the opportunity to change or modify their prints later in the semester, they will again be confronted with how these features contribute to its message. I asked Kathleen to share more about her assignment, the implementation of this first phase, and how the students applied their interpretations in the classroom:

“Bringing Symbols to Life” is intended to provide students with new ways of examining and expressing the symbolic world of Russian self-identification. Symbols take on new meaning when we can actually manipulate and interact with them, rather than simply seeing them on a page. Interacting with an object allows us to differentiate between ‘symbol’ as an abstract and ‘object’ as a thing; if an object is decontextualized and recontextualized, is it still a symbol of Russianness? What assumptions do we make about symbols of Russianness, and how can we challenge those assumptions?

The ‘scales of justice’ as it prints. The students also printed two cubes–one white, one red–to represent conflicting forces on each side of the scale.

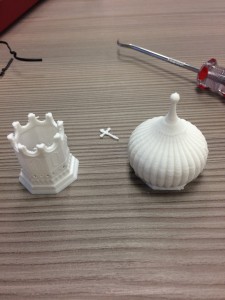

To answer these questions, groups of 6-7 students collaborated to choose and print a 3D object that, to them, represents Russia. We chose to have students print 3D objects, rather than simply view photographs or slides, because we suspected that having a tangible physical object that they would have to create and then handle would give them a new perspective on how Russians think of themselves. They presented their objects during the second week of class, along with a brief justification of the object they chose and its usefulness as a symbol of Russian identity. The six groups chose the following objects: a bust of Joseph Stalin, a Rubik’scube, the onion dome of an Orthodox cathedral, a Soyuz rocket, St. Basil’s cathedral, and a set of unbalanced scales containing a white box and a red box on each side. Having the items present in class, and able to be touched and passed around, fostered what we think was a more robust discussion of identity than a set of images on a page – for example, being able to see up close the many intricate parts of St. Basil’s cathedral that make what one group called it a symbol of “chaotic Russia”, where cultures and traditions coexist yet also clash, seemed more meaningful than simply looking at it on a screen. The Rubik’s cube and the scales spurred the most discussion, as students noted not only the scale’s metaphorical representation of a power imbalance between Russia and the West, but also its literal imbalance and fragility as a model (it had to be handled very carefully due to its delicate construction). The Rubik’s cube, which was meant to represent what its group called the “polyperipheral” environment, history, and geography, inspired students to discuss scientific and mathematical components of Russian identity and the ever-present Russian fear of feeling “left behind” in technological advancements.

St. Basil’s Cathedral, iconic landmark in Moscow.

The onion dome of St. Basil’s Cathedral before assembly.

Students are currently designing and curating two physical exhibits of their objects: one in the Makerspace in Alderman Library, and another in the Slavic Department’s hallway on the second floor of New Cabell Hall. Since creating two exhibits means that objects have to be printed twice, students may alter (or switch entirely) their objects if they choose, provided they give justification. The Rubik’s cube group, for example, expressed interest in re-printing their cube to make the parts movable, which they said would better reflect the changes that “polyperipheral” Russia has experienced especially in the last twenty years. Throughout the semester, students will also revisit their objects to examine how they might function as expressions of Russian identity in various contexts, and at the end of the semester, they will write and present longer reflections on their objects as useful symbols.

Starting February 25th, all printed icons of the “Bringing Symbols to Life” exhibition will be on display in the Slavic Department display case, located outside the Slavic Department offices in 258 New Cabell Hall.