A review of the suffragette game

I think Scott’s review of our Ivanhoe game play is insightful and timely, and it has inspired me to consider the once-thriving-but-now-dormant “citizen journalism” game. I think it’s time to really look into the successful games and, aside from the fact that we could see what was going on more immediately via the email medium, examine what else contributed to their being taken up with such vim. I think an element of fun is paramount. The sci-fi people (Bethany, Eliza, Eric, Scott, and Veronica all contributed) played a game on Galaxy Quest Chompers entitled “Sci-fi Fun,” and the journalism people (Eliza, Francesca, Zach, Veronica, and I) began playing around with–and even revising–a major moment in history: c. 1909 women’s suffrage in England. As the beginner–and as of right now, the finisher–of this game, I would like to review the major moves made and directions our game took in anticipation of building on them in Round 2 of game play.

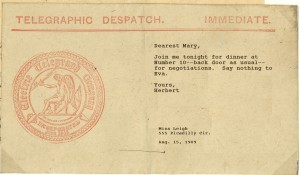

The premise: a mysterious first-person narrator discovers a news clipping with this photograph in her mother’s trunk. The narrator says, “She had always fallen strangely silent when asked about the movement; perhaps now I might finally learn more about that momentous day in her life. I began to read.” This was all presented in email form, with the photograph pasted into the email. The idea was to prompt reflections on the photograph, contributions to what the article might have said, and explanations for why the mother wouldn’t want to talk about the movement. I figured that such a setup was open-ended enough to allow for creativity, topically engaging and therefore open to critical evaluations regarding feminism and history, and focused– which the Poe game was not.

Eliza rapidly authored a wonderful article on the suffragette plot to assassinate Prime Minister Asquith–which I thought was a colorful fabrication until she informed me that it was a true event. Because I had framed the game in fiction, I assumed that subsequent moves would be fictional; from the get-go, the line between history and alternative history had been blurred. In the spirit of fun, I concocted a secondary plot line in which Asquith had an affair with suffragette Mary Leigh–totally fictitious. I constructed this story in the form of telegrams and letters the narrator, Mary Leigh’s daughter, discovers in her mother’s trunk.

Then, Mary’s daughter by Asquith (Etta and the narrator) falls ill, and she writes him about her illness (fictional); Mary gets thrown in prison, engages in a hunger strike, and gets force-fed (contributed by Zach and true); and Asquith’s wife and his daughter Violet get involved in the suffrage movement (contributed by Veronica and probably fiction?). Francesca contributed an interview with Mrs. Banks,) a delightful homage to Mary Poppins; Mary Leigh seeks Poppins’ services for Etta; and all the women in Asquith’s life–wife, mistress, and daughters–band together in the end for the sake of Women’s Suffrage (my move and meant to be a Golden Move of sorts, as the game by that point was indeed “fizzling”).

The game clearly was a blend of delving into real history and absurdity. A debate took place in one of our Praxis meetings shortly after the game had begun: was there a use to engaging in alternative history in this way? The conclusion was that it depended on your purpose: if the goal is to establish fact in a historical research project, then sticking to fact is best; if, however, you are attempting to think in more outside-the-box ways about history, then breaking into alternative history could inspire new ways of interpreting a particular historical moment.

In analyzing my game play, I realize that I was consistently attracted to ironies: the irony of Mary Leigh trying to influence Asquith to give women the vote by seducing him, the irony of her leaving her daughter every day and seeking Mary Poppins’ assistance while she protested for that same daughter’s rights (“Our daughters’ daughters will adore us…”), etc. This was not to impose a particular criticism on this moment in history, but rather to parse out experiential elements–hypothetical effects these women’s public lives could have had on their personal lives and vice versa. After all, even in Mary Poppins, Mrs. Banks asks her maid to hide their suffrage ribbons as she hears Mr. Banks at the door, saying, “You know how they infuriate him.”

Francesca’s contribution of Mary Poppins was lighthearted and fun, but it got me to thinking about Mrs. Banks, so enthused about the movement that Katie Nanna’s giving notice (where the video breaks off) and the need to find a new governess to care for the children is an interruption. We could have stayed more grounded in our Ivanhoe, but I think that by blending historical with alt-historical moves we ended up with a provocative game which, for me at least, prompted some interesting and troubling musings on gender politics. Altogether, I think it was a very successful Ivanhoe, and I look forward to the ideas new games may produce.