Anxiety and the Monte Carlo Method

The Praxis Program fellowship will shortly undergo dramatic funding changes as consequences of UVA Library austerity budget cuts (as Brandon Walsh has thoughtfully documented in his recent post). Starting the next academic year, we will no longer be able to buy out our fellows’ teaching obligations. One consequence of this is that they will have a substantially larger number of fixed times where they cannot attend Praxis sessions. The modern Praxis curriculum consists of two 2-hour sessions in a typical week, and it has occasionally been irksome to find times to meet for 5 fellows even when they did not have to teach. With decreased availability, I am anxious that this problem will become insurmountable and the program that we have refined over fifteen years will need to be substantially reconfigured. My way of coping with this anxiety is to crunch the numbers, under the dubious theory that having greater insight about future calamity will make it easier to face. So, what’s the likelihood that we’ll be able to find two free slots a week in common, assuming that each student has a certain number of hours that are already taken? At what point does this number drop off?

The problem is that I don’t really know anything about statistics. I have to look up combination and permutation every time to know which one is which. Happily, for people who know how to code but don’t know how to do stats, there’s the Monte Carlo Method. If we can straightforwardly model the rules of a problem, but it’s onerous to map it to an abstract statistical approach, we can just have a computer try out different random permutations (or is it combinations?) over and over again to create an approximation of the outcome.

In this case, we start with assuming 8-hour workdays and a 5-day workweek, 5 students, and some variable number of hours each week when the student will be teaching (or other inflexible obligations). To simulate the scheduling for one semester for a given number of obliged student-hours, we can start by assuming that these obligations are evenly distributed across the entire week. Then, we create a random schedule for each student, represented by a boolean list of length 40. Since we only really care about when every student is free, we can just take the union of all the times they are busy. After that, we can simply check if there are two 2-hour blocks of contiguous free time to determine the outcome of this run.

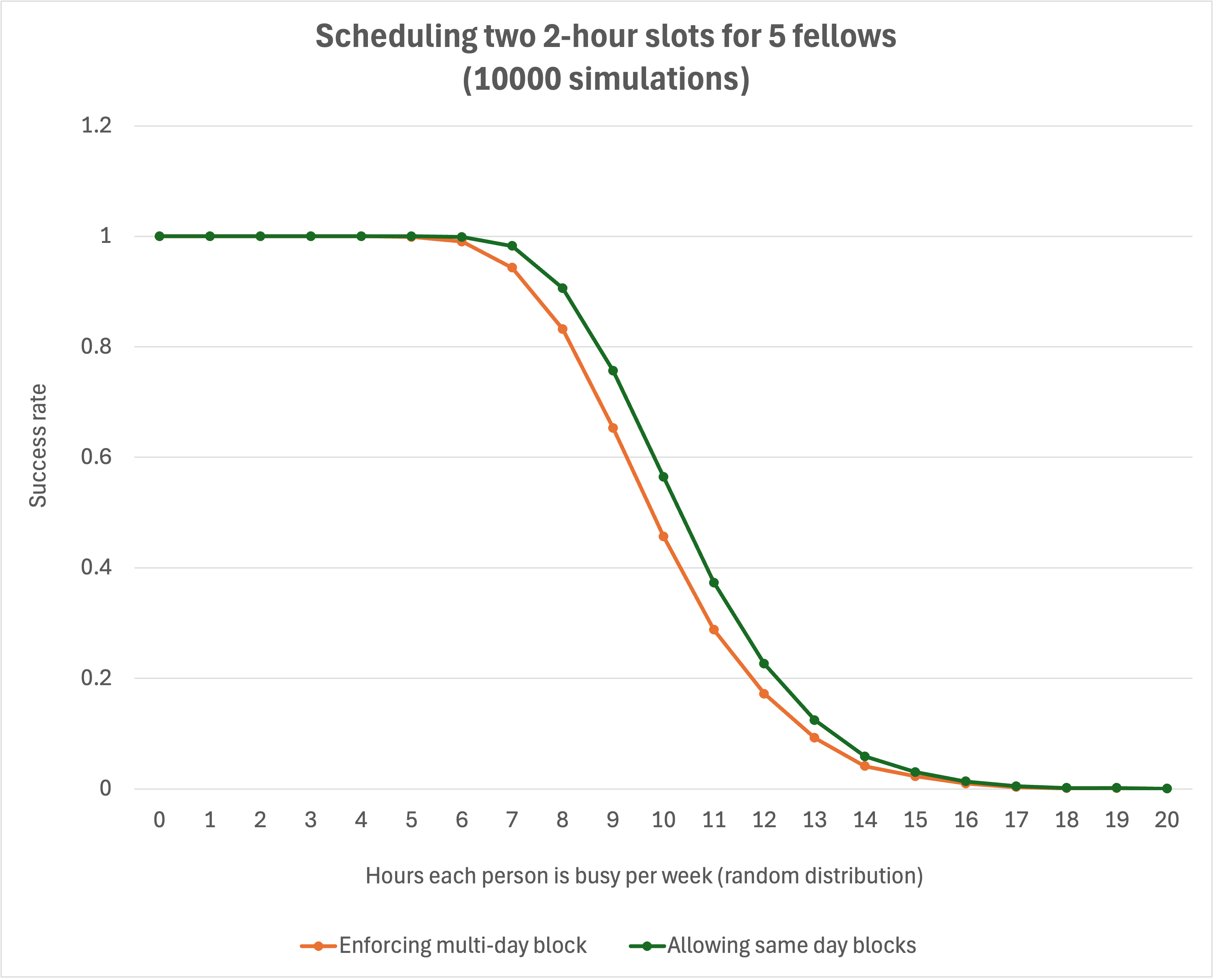

Arbitrarily, we can run this 10,000 times for each number of obliged hours per week from 0 to 20 and graph the results.

Here, I’ve also run the numbers for both the case where we enforce that each session be on different days (ideal) or if we will allow them to be on the same day (barbarous) to see if that unenviable prospect buys us anything. From this graph, we can see that, either way, there’s a pretty steep drop-off starting at 8 hours and falling below 50% success rate at 10 hours. Allowing sessions to be on the same day only gets us about 0.5 hours of leeway, which doesn’t seem worth the torturous cost. Typically, a graduate teaching assistant for a single large course may be required to attend three hours of classes and preside over three more hours of discussion sections in a week. There are many more obligations that are either more flexible or require less time, but this represents a reasonable floor for our consideration. This means that we’re relying on students having at most about 2-4 additional hours a week of fixed obligations before we are likely to be in trouble.

There’s a lot of assumptions here and we can maybe make our model more complex using, say, real historical course schedule distribution data from Lou’s List, but I think this does provide a reasonable initial approximation.

So does this make me feel better? Maybe, sort of, yes. The numbers aren’t great but there is a narrow path to success. And I think this is also helpful in that it gives us a lot of time to put mitigation strategies into motion, some of which may also be strengthened by having these numbers. Maybe we can act sooner and steal a march on other, easier to schedule things or work with our fellows’ home departments. And maybe I’ll just keep playing around with refining this model with Lou’s List datasets, just for the sake of anxiety.

Here’s my code, just in case it’s useful for anyone.

"""

Simple simulation of Praxis scheduling

"""

import random

import csv

NUM_PEOPLE = 5

SIMULATIONS = 10000

ENFORCE_MULTIDAY = True

DAYS = 5

HOURS_PER_DAY = 8

# track separately the outcome if we enforce

# multi-day and if we allow same day sessions

success_rates_multiday = [0]*21

success_rates_sameday = [0]*21

for hours_busy in range(21):

successes_multiday = 0

successes_sameday = 0

# Iterate over simulations

for i in range(SIMULATIONS):

busy = [False] * DAYS * HOURS_PER_DAY

# For each person, independently mark off hours_busy hours as busy

# Result is a list of DAYS*HOURS_PER_DAY booleans representing slots

# where each person is busy (True) or free (False)

for j in range(NUM_PEOPLE):

for k in random.sample(range(DAYS * HOURS_PER_DAY), hours_busy):

busy[k] = True

# Calculate successes if we enforce multi-day slots

# Split busy slots into days

days = [busy[i*HOURS_PER_DAY:i*HOURS_PER_DAY+HOURS_PER_DAY] for i in range(DAYS)]

days_free = [False]*DAYS

# Determine if each day has a free slot or not

for k in range(len(days)):

d = days[k]

# a day is free if it has two consecutive free hours

days_free[k] = any(not a and not b for a, b in zip(d, d[1:]))

if sum(days_free) >= 2:

successes_multiday+=1

# Calculate successes if we allow same-day slots

count = 0

i = 0

while i < len(busy) - 1:

if not busy[i] and not busy[i+1]:

count += 1

if count == 2:

successes_sameday+=1

break

# skip ahead to avoid overlap

i+=2

else:

i += 1

success_rates_multiday[hours_busy] = successes_multiday/SIMULATIONS

success_rates_sameday[hours_busy] = successes_sameday/SIMULATIONS

with open("freeslots.csv","w",encoding="UTF8") as fp:

fieldnames = ["Hours busy per person", f"Success rate enforcing multi-day slots", "Success rate allowing same day slots"]

csvwriter = csv.writer(fp)

csvwriter.writerow(fieldnames)

for i in range(21):

csvwriter.writerow([i,success_rates_multiday[i],success_rates_sameday[i]])