Segregated Biographical Collections and Documentary Social Networks: Portraits of American Women and Women of Distinction

A Co-authored Series of Posts ‘About 1919,’ that is, about English-language books published from 1914 to 1921, according to the online bibliography and database, Collective Biographies of Women.

Collective Biographies of Women’s eponymous genre almost naturally gives rise to network analysis. In the same way that researchers today look at social networks (online or otherwise) and think about the meanings of “connections” or “nodes” within them, so too can we look at collective biography as a mode of textual and social connection. Collective biography is sometimes called prosopography, a method of studying sets of people as “parallel lives,” to echo the title of Plutarch’s classic prosopography of the lives of Greeks and Romans (widely read in the nineteenth century). Each time we look at a table of contents in CBW, we are presented with a suggested grouping. Here, the author and publisher say, are women who belong together. Yet we call these connections a documentary social network, unlike an actual one built by letters, meetings, relationships. The subjects of the chapters in a collection often had no interaction with each other but lived in different centuries, countries, or social circles. Nevertheless, prosopography strives for measurable comparison by carefully documenting as much as can be known about individuals in the comparative network.

A woman’s life narrative may belong in more than one place. One of the main ways researchers at UVA have been using the CBW database has been to compare the recognition rate, our term for how many times an individual appears in tables of contents across the database. This rough measure of person A’s and person B’s relative usefulness as examples can be even more revealing in our study of networks, discussed in a moment: how often do A and B get placed together in a book of women’s lives? For now, think of a woman like Abigail Adams, who predictably appears in collections of revolutionary women, of first ladies, of the mothers of presidents, and of American women more generally. See: the prolific historian Elizabeth Fries Lummis Ellet’s The Women of the American Revolution, first published 1848 a259; almost a century later, Kathleen Prindiville’s First Ladies in 1932 a654. During World War I, Adams resurfaces in William Judson Hampton’s 1918 collection, Our Presidents and Their Mothers ([a374] (http://cbw.iath.virginia.edu/books_display.php?id=1705); and again in Gamaliel Bradford’s Portraits of American Women in 1919 (a102). Bradford’s distinctive career as a biographer is featured in Mackenzie Daly’s post, third in this series.

What might it mean for a person–versions of a historic woman–to occupy various positions, inherent in the tables of contents she appears in? What kinds of documentary social networks arise? In the realm of collective biography, how can we quantifiably discuss “connectivity”? Probably, a high “recognition rate” (RR) will indicate that a person was (at the times when the collections were published) far from obscure. But this measure of status may not correlate with the actual rank or power of a particular woman during her life. We see some isolated, single-biography subjects in CBW were once upon a time queens. Some 6000 women appear only once in CBW’s 15,000+ biographical chapters. All of these measures resonate with the narratives themselves as our team tags them with an XML schema. Does a person’s relative connectivity correspond to that murkier (but perhaps more intuitive) notion of “obscurity”? Do either of these aspects of a person make any difference to how their story is told?

In this blog, I’ll try to answer each of these questions in turn. As examples we’ll look at two collections both published 1919, just in the aftermath of World War I. The first was noted above for including Abigail Adams: a102 Portraits of American Women by Gamaliel Bradford (Houghton Mifflin, Boston). Its counterpart here is a108 Women of Achievement by Benjamin Griffith Brawley (Women’s American Baptist Home Mission Society, Chicago). These volumes make different claims to speak for the mainstream, by highly educated men, one an academic historian, addressing general readers.

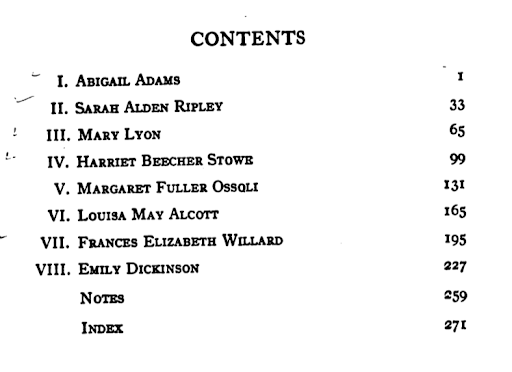

Table of Contents for a102 Portraits of American Women (HathiTrust)

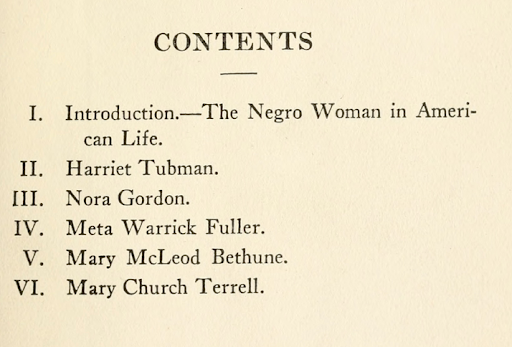

Table of Contents for a108 Women of Achievement (HathiTrust)

As the word “Negro” in the table of contents underlines, Brawley’s featured women have achieved in a context of racial discrimination. Readers might have guessed a criterion of selection that the titles don’t tell by looking at the publishers and cities on the copyright pages: Houghton Mifflin is a prominent New England publisher to this day and the American Baptist Home Mission and its Women’s offshoots in the East and Midwest continue to work with the poor and people of color. A closer look, and we find that all of Bradford’s eight subjects are white, without remark. Brawley’s five biographical chapters portray African-American women under the non-racial rubric, “women of achievement.”

“American” has a meaning in both books that presumes whiteness as default. “Home” refers to missions like the Salvation Army (originating in London as “Christian Mission” and launched in the U.S. in 1880) or Jane Addams’ Hull House that serve onshore rather than in foreign lands. Addams, 1860-1935, RR=21, and many other American female leaders of home missions were white, not Baptist, and would not fit in Brawley’s book. Collective biographies published in the U.S. often focus on varied nationalities, yet these two are invested in defining American women.

The database and other resources identify Bradford as a white man and Brawley as a Black man, contemporaries. Gamaliel Bradford VI, born in Boston before the US Civil War (9 October 1863 – 11 April 1932), was the grandson of an abolitionist namesake and educated at Harvard, who became a well-known biographer (see Mackenzie Daly’s blog). Brawley (22 April 1882 - 1 February 1939) was born in a middle-class minister’s family in South Carolina and earned a BA from University of Chicago and MA from Harvard before serving as Dean of Morehouse College and later teaching at Howard; he was a prolific poet and published a range of histories of African Americans, college texts and literary criticism, and autobiography. Brawley in his day was well-known in African-American elite circles. Bradford gets mentioned in literary histories of biography.

These rather short-list collections identify a range of female achievers most of whom are well-known now, though early in the twentieth century biographical sources on the recent and living Black women would have been scarce. Whereas Bradford’s “psychographies” portray a New England “American Renaissance” canon before the twentieth century, Brawley’s starring roles in 1919 include Meta Warrick Fuller, a versatile artist who lived until 1968, and national leaders Mary McLeod Bethune and Mary Church Terrell, whose most famous achievements occurred between World War I and their deaths in the 1950s. Both biographers portray female character and public action, broadly a cause of progress for their sex and their nation, while Brawley’s volume overtly supports an organized social mission. There is a race-based time lag, in a sense; activism calls for recognition of more obscure, living workers for the cause.

Documentary Social Networks and Degrees of Separation

As with other social networks, these women can be thought about in terms of degrees of separation. To be precise—if Woman 1 and Woman 2 appear in the same book, they have a degree of separation designated 1 (the CBW team has dubbed them “siblings”). If Woman 2 and Woman 3 appear in the same book, but Woman 1 and Woman 3 do not appear in the same book, then Women 1 and 3 have degree of separation 2 (and we can call them “cousins”). In this blog post, we shall consider as many degrees of separation as possible for a woman: call them, perhaps, third or fourth cousins. While we see the significance of this sort of measure by looking at two 1919 publications, I used the searches of tables of contents across the database of 1272 books to generate relative degrees of obscurity or connectivity. (CBW’s radial graph for visualizing degrees across tables of contents is being redeveloped; ask Alison Booth, email ab6j@virginia.edu.)

For each woman in the two collections I looked at, I determined their connectivity within our database of collections by finding the total number of women listed in contents at each degree of separation, up to 6 degrees of separation. I then used those numbers to determine “average degree of separation”—let us, to use a spicier term, call it “d-factor.”

Thus, Abigail Adams has 601 siblings, 3994 cousins, and so on. Here are the results for Portraits and Achievement represented in tabular form:

A102 Bradford, Portraits

| Person | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | d-factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADAMS | 601 | 3994 | 2783 | 148 | 0 | 0 | 2.32925857 |

| RIPLEY | 7 | 1416 | 5600 | 487 | 16 | 0 | 2.878952963 |

| LYON | 201 | 4893 | 2347 | 85 | 0 | 0 | 2.307733192 |

| STOWE | 588 | 6218 | 691 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 2.021392506 |

| FULLER | 418 | 5700 | 1340 | 68 | 0 | 0 | 2.140579325 |

| ALCOTT | 467 | 6105 | 903 | 51 | 0 | 0 | 2.071485517 |

| WILLARD | 224 | 5375 | 1875 | 52 | 0 | 0 | 2.233191602 |

| DICKINSON | 180 | 4766 | 2467 | 113 | 0 | 0 | 2.333909115 |

A108 Brawley, Achievement

| Person | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | d-factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TUBMAN | 482 | 471 | 2244 | 85 | 0 | 0 | 2.256675967 |

| GORDON | 187 | 580 | 5281 | 1422 | 57 | 0 | 3.077321642 |

| FULLER | 30 | 797 | 5245 | 1420 | 35 | 0 | 3.08409725 |

| BETHUNE | 341 | 4786 | 2284 | 116 | 0 | 0 | 2.288959745 |

| TERRELL | 188 | 579 | 5281 | 1422 | 57 | 0 | 3.077188787 |

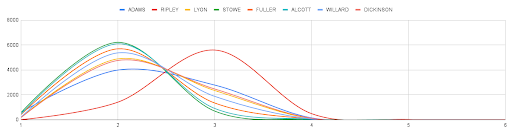

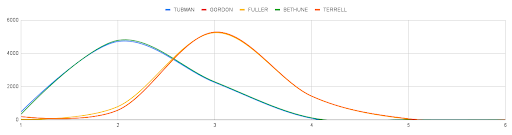

Stowe and Alcott have the lowest d-factors of this array of women, that is, we might say the highest connectivity. And here is the data presented graphically. In the graphs below, the X axis represents degrees of separation and the Y axis represents the number of connections at that degree of separation.

A102 Bradford, Portraits

A108 Brawley, Achievement

It’s difficult to assign too much meaning to the absolute values of these women’s d-factors, but these measures add significance in comparisons and contexts across CBW, including the narrative methods themselves. Further analysis might show tendencies such as fewer episodes or descriptive passages correlating with longer tables of contents and perhaps higher rates of “singleton” subjects (RR=1). To write a biography of a rare subject or a living person who has been little documented generally takes more time and effort than to patch together and embroider from previous printed sources. For the audience, too, the familiar biographical subject may be preferable. The supply and demand economics seem not to apply strictly when circulating the name and narrative of a historic person. Less separation (closer association between two women and their associates in turn) can indicate being closer to the centrality of a national history, and higher probability of cropping up in a table of contents of lives of women of any type. Ripley, with RR=1 (solely in Bradford) has a d-factor slightly larger than Mary Lyon, RR=20.

It’s more interesting to think about them in relation to each other. We can say that a woman with a d-factor of 2 is certainly more closely linked to the mass of other women appearing in our database than a woman with a d-factor of 3. A woman with a d-factor of 2 is more closely connected to the rest of the database than a woman with a d-factor of 2.3; though this difference is nowhere near as intense as the first example, it is still quite significant. In the tabular data above, for instance, look at the disparity between Louisa May Alcott and Harriet Tubman. Though both are 1 degree of separation from roughly the same amount of women (467 vs. 482, respectively), Alcott is 2 degrees of separation from over 1000 more women than Tubman is. This difference, which could be attributed both to the wider social networks of a white woman in New England who published widely and to the bias of CBW books’ documentary networks–their tendency to privilege white women writers, for example. Their respective d-factors, in small but telling averages, reflect this: Alcott 2.07; Tubman 2.25.

You might expect d-factor to simply correlate to the number of chapters about a woman in the volumes in the database, her recognition rate (RR) as we call it. But at a different level d-factor helps showcase how some women are more likely to be connected to specific well-connected women. It is another way of displaying “fame” or “notability,” and with d-factor we can begin to surmise about the distinctions in obscurity between women brought together into the same collection. Some, I suppose, will be “central nodes,” and others will be more “peripheral.”

As we can see from both representations (but more quickly in the graphs), both Bradford’s and Brawley’s collections have two identifiable subsets of women. Broadly, Portraits is divided into Sarah Alden Ripley and everybody else, with Ripley the least “connected” woman with RR=1 (Bradford alone of 934 authors of CBW’s texts decided to include her in a collection). Comparably, Achievement is divided between Gordon/Fuller/Terrell and Tubman/Bethune as, respectively, less connected and more connected women. An effort has been made to equilibrate the two graphs’ size, but note that their y-axes have different maxima.

Achievement’s women seem to have low deviance within those two groups, at least compared to the group of Portraits’s women with a d-factor near 2. Particular attention ought to be paid, again, to Abigail Adams, who in spite of having the highest number of siblings (1 degree from her), has a relatively low number of people 2 degrees of separation from her. We speculate that this lower indirect (cousinly) connectivity may be due to Adams’s tendency to appear in the same book with wives or mothers of U.S. presidents, as we already have seen, rather than in more mixed tables of contents with varied subjects. We could explore this for other types of American women.

Now, does any of this affect the way the author tells the story? That is, does a person’s relatively low d-factor (a quantity that the author would not directly know but may have some proxy conception of)—change how their story is told? Let us localize this discussion to the introductions of the works in question.

We see an authorial awareness of obscurity in the first paragraph of Bradford’s lone obscure biography, for Sarah Alden Ripley (who happened to be his relative): Few American women of to-day know of Mrs. Samuel Ripley, but a sentence from Senator Hoar’s “Autobiography” will give her a favorable introduction: “She was one of the most wonderful scholars of her time, or indeed of any time. President Everett said she could fill any professor’s chair at Harvard.” Contrast this introduction with the way he introduces Frances Willard (“She had the great West behind her; its sky and its distances…”), Louisa May Alcott (“Her father thought himself a philosopher…”), and Harriet Beecher Stowe (“She was a little woman, rather plain than beautiful…”). With Ripley there is something of a necessary justification, an initial pivot to a secondary source which proves that she belongs with the subjects of the other chapters, and at the same time an implicit criterion of inherent, merited but uncrowned achievement. With Ripley as contrast, we see more clearly what the biographer can do when they work with a well-known biographical subject: dramatize, begin in medias res, take advantage of the fact that the reader is coming back to someone familiar, so that the introduction is really a reacquaintance. Ripley, with a higher d-factor, earns Bradford’s least artful flourish of narrative technique in her opening sentence: the lower the d-factor, the less an introduction needs to actually introduce.

That, at least, is the conclusion I can draw from Portraits. But does looking at Achievement change that thesis at all? Let us see how Brawley introduces his two “well-connected” women (Tubman and Bethune) vs. his three “obscure” women. [^bignote]

Tubman: “Greatest of all the heroines of anti-slavery was Harriet Tubman.” Bethune: “On October 3, 1904, a lone woman, inspired by the desire to do something for the needy ones of her race and state, began at Daytona, Florida, a training school for Negro girls.”

Gordon: “This is the story of a young woman who had not more than ordinary advantages, but who in our own day by her love for Christ and her zeal in his service was swept from her heroic labor into martyrdom.” Fuller: “The state of Massachusetts has always been famous for its history and literature, and especially rich in tradition is the region around Boston.” Terrell: “With the increasingly complex problems of American civilization, woman is being called on in ways before undreamed of to bear a share in great public burdens.”

It is more difficult to make the same argument out of these quotes as we did with the Bradford book. Might Brawley be working in a different mode altogether? We see that Tubman, by far his most famous subject, least requires citation to an external authority in his introduction. Alternatively, we might say that Tubman’s importance demands his respect, his summative statement of her greatness. Could there be a difference to writing Black biographies vs. writing white biographies, that manifests in this particular manner?—that is, to deal with a “well-known” persona unlocks a white biographer’s capacity to do away with formality, but absolutely necessitates formal announcement for a Black subject. Bradford indulges in his breezy approach favoring interiority and impressions upon the security of generations of New England insider status. Brawley, in spite of his academic credentials and prestige, knows his Black women needed to dress in their Sunday best to be classified as “American women” or “women of achievement” without the racial modifier. Such inequities might appear in the more formal, grander dressing of Brawley’s subjects.

These are just a few considerations, a starting set of theses. As with much digital humanities research, this brief discussion has offered more questions than it has answered. It has hoped to provide a new quantity for potential analysis, applicable most readily in the CBW database but, with some trivial modifications, easily applicable in similar databases representing networks of people–similar prosopographies.