Death Politics in Collections of Indian Women’s Lives

While reflecting on the early deaths of poet Toru Dutt (1856—1877) and doctor Anandibai Joshee (1865-1887), Mrs. E.F. Chapman notes that “for them as well as for their country the poet’s words may be true —The fairest gift that life can give/ Is to die young.” Alone, Chapman’s musings on the early deaths of two of the five Indian female subjects in her biographical collection Sketches of Some Distinguished Indian Women seems inconsequential. Using BESS analysis, however, to compare Chapman’s 1891 Sketches of Some Distinguished Indian Women with Mrs. E.J. Humphrey’s similarly titled 1875 Gems of India, Sketches of Distinguished Hindoo and Mahomedan Women reveals a preoccupation with Hindu women’s deaths which betrays the biographers’ rhetorical purpose: encouraging Christian women to save Hindu women from their faith traditions.

Chapman and Humphrey draw their “sketches” of Indian women differently. Humphrey tackles twelve biographies of Indian women preceding and during the British colonial period in Gems of India; Chapman writes five biographies of women both living or recently deceased, exclusively during the British colonial period. The two authors also write to different audiences. Humphrey publishes her collection in America; Chapman publishes her collection in England. Humphrey dedicates Gems of India in 1875 to “American Women, of whatever religious denomination or creed” and, writing from the perspective of a missionary who lived in India several years, invites them to bring Christianity to India. As she writes in her conclusion, “The work of making the women of heathendom acquainted with our holy religion belongs more fitly to the women of Christendom” (205).

In contrast, Chapman appeals less explicitly for religious conversion, and more for female education and social liberation. She published her collection in 1891, nearly twenty years after Humphrey, at a time when Chapman notes that English and American readers were inundated with narratives about the trials and tribulations of Indian women. Chapman writes that these existing narratives “painted in dark and forcible colours the picture of [Indian women’s] degradation, their helplessness, their ignorance” and the “dull, empty, colourless lives of even the happiest among them” (2). Chapman argues that her collection Sketches of Distinguished Indian Women provides “a brighter side to the picture” (2). Whose story is “bright”and whose is comparatively “dark” is the subject of this blog post.

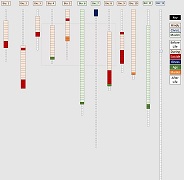

While BESS explores a range of elements, notably events, discourses, persona descriptions, and topoi, this analysis focuses on the Stage of Life element, which delineates the part of the text which narrates events in different stages of a person’s life: before, beginning, middle, culmination, end, and after. The charts below, Figures 01 and 02, map the Stage of Life across the biographies in both collections. Take the first biography (Bio01) in Gems of India, which narrates the life of princess Sanjogata, as an example. Starting from the top, the white squares represent paragraphs which narrate events that take place before Sanjogata’s birth, the colored boxes events which take place during Sanjogata’s life, and the white boxes below the events which took place after Sanjogata’s death. The darkly colored squares delineate how Sanjogata and the other women in the collection died, tragically by suicide, unexpected illness while still young, murder, or naturally by age. Finally, the women’s religions are also marked: light orange for Hindu women like Sanjogata, light blue for Christian, and light green for Muslim.

Figure 01: Stage of Life and Religion Graphic for Gems of India by Mrs. E.J. Humphrey. Collection a430.

Figure 02: Stage of Life and Religion graphic for Sketches of Distinguished Indian Women by Mrs. E.F. Chapman. Collection a156.

While Chapman and Humphrey approach their sketches of Indian women differently, BESS demonstrates that both authors share a kind of “death politics” within their collections. If you look at the figures, without even reading the biographies, you can tell that while Christian and Muslim women are spared from early deaths; Hindu women are not. Using BESS to compare the two collections reveals that while across both collections only 52% of women die in sad or violent ways, 72% of the Hindu women do. Six of the eight Hindu women in Gems of India die violent deaths, either by murder or suicide, notably suttee, self-immolation on a loved one’s pyre. Two of the three Hindu women in Sketches of Distinguished Indian Women succumb to illness and die early. Across both collections, only one non-Hindu woman dies early — a Muslim woman, empress consort Mumtaz Mahal (1593-1631) (Bio07); however, Humphrey only devotes three paragraphs to narrating the events of her life 1.

The women who die natural deaths are also equally involved in this “death-politics” and, in fact, may make the rhetorical strategy of the editors more apparent. The Hindu women who do not die early or violently are friends with imperial powers, or else the author dedicates time to instead narrate the dramatic death of a loved one. In Gems of India, only two Hindu women do not die violently- Jodh Bai, or empress consort Marium-uz-Zamani (1542-1623) (Bio04), and ruler Ahuliya Baie (1725-1795) (Bio08). Mariam, while Hindu, married into a Mogul Muslim dynasty, rather than marrying another Hindu royal or following caste rules and Hindu traditions. While Ahuliya Baie is described as religiously Hindu, Humphrey graphically narrates the suicide of Ahuliya’s daughter by suttee and its effect on Ahuliya across multiple paragraphs. “Poor Ahuliya Baie” Humphrey extorts. “Although a queen of a million people, she was poorer than the humblest Christian woman of today who can sing in the assurance of faith.” Likewise, in Sketches of Distinguished Indian Women, Humphrey praises Maharani Sunity Devi (1864-1932) (Bio03), the only Hindu woman still alive when the collection was first published, as a fervent friend and supporter of the British in India. The Hindu women spared early and violent deaths are either withdrawn from Hindu society, or else witness violence directly correlated to their faith. In summary, no Hindu woman lives as a practicing Hindu among other Hindus without suffering tragedy.

This is not to say that the authors are only attempting to persuade their readers about the danger Hinduism poses for Indian women - the editors do not narrate tales of “honor killing” or women’s abuse. Instead, even those women who are murdered are killed for defending their nations. When the women commit suicide, they sacrifice their lives for honor, for their communities, or for love. Across both collections, how these Indian women die betrays a rhetorical strategy which venerates Hindu women’s sacrifice. In Gems of India, six of the Hindu women’s narratives depict at least one scene of female suicide, and despite none of Chapman’s female subjects committing suicide, she dedicates pages of her introduction to defining suttee, its practice, and its prohibition. Similarly, while Chapman’s Hindu women die of illness rather than violence, she portrays the young women’s deaths as sacrifices for their nation. On Anandibai Joshee (Bio02), Chapman writes: “She sacrificed her life in the endeavor to bring help and relief to her suffering fellow countrywomen, and who shall dare to say that her sacrifice was in vain, or that her early death may not stir others up to follow in her footsteps.”

However, Anandibai Joshee (Bio02) and Toru Dutt’s (Bio4) sacrifices are not to defend India against invasion, but rather sacrifices to import Western education and ideals. After narrating the early death of Toru Dutt, Chapman draws a thought-provoking connection between travel to Europe and America and death. The two women who die young both spend a longer time in England and America than does their Hindu counterpart, Sunity Devi (Bio03). While the Christian women who travel abroad survive, the two Hindu women do not. Instead, the young Hindu women are sacrificed on the altar of Westernization, martyrs for the cause of bringing English and American learning to India. Chapman associates the cold and damp weather to the women’s deaths, and cites the poetic verse I opened this essay with: “Yet, perhaps, as we mourn these early deaths, these gifted women taken from us, as we think, all too soon, we may be at fault, and that for them as well as for their country the poets words may be true - The fairest gift that life can give/ Is to die young.”

Figure 03: Stage of Life and Travel graphic for Sketches of Distinguished Indian Women by Mrs. E.F. Chapman. Collection a156.

For both Humphrey and Chapman, the greatest gift Hindu women can give is their lives. Despite all their accomplishments, Hindu women were denied the happy endings their Christian and Muslim counterparts are otherwise allowed. The emphasis on their self-sacrificing deaths recalls the martyrdom of saints in hagiography, compellingly sketching “heathen” women in the style of Christian icons. As Hermione Lee identifies as originating in stories of the lives of saints, the Indian women’s biographies exemplify “the tension that biography produces between wanting to identify and emulate, and wanting to know about a life inconceivably different to one’s own.” While Indian Christian women’s lives could be emulated, Hindu women’s lives were to be pitied, sometimes praised, but not to be imitated. Their lives were sources of historical and cultural education about India, and their deaths evidence for the continued Orientalist belief in Western superiority over the so-called East.

While Chapman claims that Sketches of Distinguished Indian Women paints a different picture of Indian women than earlier collections like Gems of India, she ultimately does little to change the narrative of Hindu women’s lives, specifically, how those lives end. As we continue to annotate more collections of Indian women’s life stories on Collective Biographies of Women, we have the opportunity to see if this “death politics” appears in other biographies, and investigate Chapman’s claim that travel to Europe and America may lead Indian women to early graves. For this example in particular, using BESS analysis to focus on Stage of Life demonstrates how the narratives’ employment of “death politics” underlies the notion that the fight for Indian women, specifically Hindu women, however fought, is a fight for the lives of Indian women. Coming to the aid of Indian women, either by supporting their conversion to Christianity or Western education, fulfills the sacrifices of the notable women whose stories the authors choose to tell. Without either, Hindu women are tragically doomed to die.

Footnotes

Sources

Chapman, E.F. Sketches of Some Distinguished Indian Women. Allen, 1891.

Humphrey, E.J. Gems of India; or, Sketches of Distinguished Hindoo and Mahomedan Women. Nelson & Phillips, 1875.

Lee, Hermione. Biography: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2009.

-

The relative longevity of Muslim women compared to their Hindu peers in these collections is worth mentioning as Muslim women often figure in the dynamic of Christian and Western salvation enforced by imperialism in the role of those who need saving; however, there are so few Muslim women across the collections that it would be premature to make a claim. ↩