#citepedagogy to Pedagogy-driven Publishing

The following contains my lightly edited contribution to the ADHO2024 session entitled “Missions Accomplished? The Future of Mission-Driven Digital Scholarship Journals in DH.” The panel had representatives from several different digital humanities journals talking about ideological underpinnings for their publications.

Hello! My name is Brandon Walsh, and I’m the Head of Student Programs in the Scholars’ Lab in the University of Virginia Library.

It’s wonderful to be with you today to talk about the Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy, a publication based out of CUNY that I have had the pleasure of working on for several years now. We are “A journal promoting open scholarly discourse around critical and creative uses of technology in teaching, learning, and research.”

My initial pitch for this group was to talk about the journal as doing more than just writing about teaching and learning: we also build pedagogy into our publishing process and infrastructure. But as I was researching for this talk I actually found that some of my colleagues on the journal’s editorial collective have already made that argument, so I wanted to first and foremost point you to their publication entitled “Who Guards the Gates? Feminist Methods of Scholarly Publishing” by Laura Wildemann Kane, Amanda Licastro, and Danica Savonick. They do a better job of articulating what I was hoping to discuss than I could, and I’d encourage you to go there first. In my brief time here I’ll just give the cliffs notes version of their work and try to build upon it. Laura, Amanda, and Danica discuss JITP in the following terms—as model for feminist modes of collaboration and inclusivity:

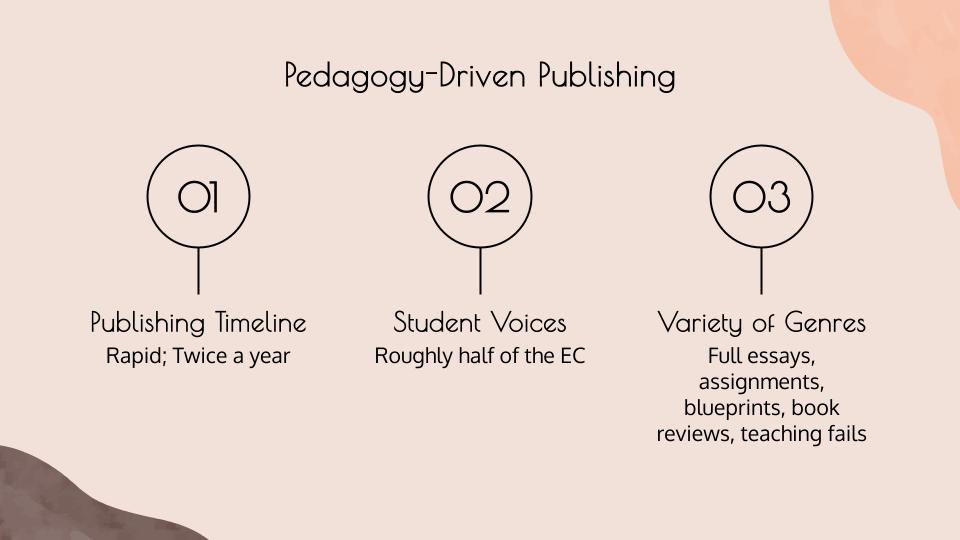

Publishing timeline - the journal publishes twice a year, usually alternating a general issue with a themed issue. This extraordinarily rapid timeline has students and early-career scholars on the job market in mind - those in need of a publication on their CV don’t have the luxury of waiting years for more traditional venues. EC student quota - the journal has written into its governance structure that the collective be between 21 and 25 active members and roughly half of those members should be students. The journal’s managing editor is also a student whose full-time gig with the journal offers him membership in CUNY’s union.

Variety of publication genres- in addition to the twice-a-year issues that share long-form essays, we publish, on a rolling basis, a variety of “short forms” that expand the kinds of work we share: assignments, teaching fails, blueprints, and book reviews. This makes it possible for students to find a range of ways to represent their work professionally. The article has lots more in it—lots of great data, history, and argument about the journal and what it means for students on the EC. It’s a space to learn about all parts of the publishing process, from editorial skills to technical web publishing literacies to inclusive and equitable publication practices.

All of this means that the infrastructure of the journal has teaching and professional development in its bones. We’re not just publishing the work of teaching: we’re baking it into the dough. Our plumbing is pedagogy. We’re not just a venue: we’re a means by which the professional development of young scholars is the core activity of the journal, where members of a scholarly unit can grow. In this way, I see our work as a natural evolution of what Matthew Gold, Katharine Harris, Rebecca Frost Davis, and Jenterey Sayers have called for under the #citepedagogy movement, which is the idea that we need to cite teaching materials and syllabi as scholarly work in their own right to make them part of the scholarly record. In short, teaching is not the thing that distracts from research output. It’s a part of it. But JITP shows that our publishing infrastructure itself can be built and rebuilt with students at the core. In short, it’s not enough to publish pedagogy. We can work towards pedagogical publication, a publishing infrastructure that cares about the needs of students and early career folks first and foremost.

Again, please check out Laura, Amanda, and Danica’s work on this. In preparing for this talk, Amanda Licastro and I actually realized we were both presenting on related topics. Amanda will be doing a follow-up presentation at MLA this year about JITP and professional development so stay tuned for that one. We recently zoomed to discuss the overlap between this talk and her upcoming one, so I want to further give her credit for my thinking on this—I’ll mention her a lot in what’s to come and I think she’s here. I want to focus on one thing in particular—the makeup of the board.

To reiterate: the editorial collective is mandated to have a certain number of student voices on it. Every time we put a call out we specify that a certain number of those selected will be students. This is fantastic - it makes it so much easier to address feelings of imposterdom with students that I’m trying to recruit because I can say “no you are exactly qualified in so many ways. We are looking for people just like you!” It means that student experience, opinion, and vision is always centered on the collective. But there are also other ways in which this makeup causes significant challenges. The thing about students is they will eventually, one way or another, no longer be students. If all goes well they will graduate and move on to better things. This sort of turnover is a sustainability problem faced by all projects and all journals—but it’s especially salient for us because even if people stay they no longer count as students. The journal’s greatest triumph is if we provide a vehicle for professional development such that our students no longer count as such. This means that a healthy editorial collective oriented in this way will constantly refresh itself with new ideas and new persons on the board. It also means, of course, that there is a constant churn—always new folks to mentor, new visions to weigh. But this is the only way to continue to keep student needs in mind. What it even means to be a student is constantly changing. Students are not the same now as they were before COVID, as they were a decade ago when I was a student. Two decades ago. Three. Every year my own memory of what it meant to be a student living paycheck to paycheck recedes into the rearview mirror and it also, either way, bears only a tenuous relationship to current student experience. We need actual student representation in order to maintain that point of view.

To ground a publishing process in student needs and experiences might be an attempt to castles made of sand, to found our publishing practices on ideological and ethical grounds that must change, by design. I’m put in mind of Jesse Mitchell’s description of inclusive design as like bathing—you’ve gotta keep doing it. Orienting a publishing process around teaching, pedagogy, professional development is an ongoing, never ending challenge. A living wage today might be untenable tomorrow. What counts as meaningful professional development for one student might not parse for another. In this way, the instability that our student focus brings is perhaps a strength. You’ve got to keep bathing. If you want to do good, equitable and ethical student-centered work you have to keep re-evaluating your priors and how you think things need to be done.

Something I’ve been thinking a lot about: what do older hands bring to publishing pipelines that model themselves on newer voices? In a journal centered around the changing needs of students, what is the role of the non-student editor? What are our responsibilities? For one, we bring memory. The ability of the institution to remember its own history is always challenged by the fact that those with the memories are likely to move on. Amanda likened it, astutely, to the efforts by Cheryl Ball and Douglas Eyman to chronicle the history of Kairos. Simply remembering is labor in its own right. I wonder how much pedagogy publishing is itself an attempt to solidify and preserve the ephemeral acts in the classroom.

There is also, of course, a certain amount of social and administrative capital that the more experienced editorial publisher can offer. A lot of what Amanda and I see our work on the collective as is to signal boost - to use our network to promote and extend the reach of the journal in a way that a graduate student might struggle with. Those networks just take time to build. I also try, at virtually every event I attend, to plug the journal and offer to people the opportunity to talk about our publishing process, how to submit, and offer feedback they might have potential article ideas. I extend this to you here and now as well! It’s a way to try to pay forward the good luck and mentoring that I have received.

There is also, of course, a certain amount of social and administrative capital that the more experienced editorial publisher can offer. A lot of what Amanda and I see our work on the collective as is to signal boost - to use our network to promote and extend the reach of the journal in a way that a graduate student might struggle with. Those networks just take time to build. I also try, at virtually every event I attend, to plug the journal and offer to people the opportunity to talk about our publishing process, how to submit, and offer feedback they might have potential article ideas. I extend this to you here and now as well! It’s a way to try to pay forward the good luck and mentoring that I have received.

In addition, Amanda works on the governance and oversight committee and had wonderful thoughts on her own relationship to that work. I love that our journal models itself on asking students to act in public as professionals and contributors to the scholarly conversation. But that process is not always smooth. It can be asking a lot for students, with little to no job security, to shoulder the weight of tense moments of internal or external conflict. It can be the responsibility of more established scholars to help shape a space for radical professional development and mentoring by doing but in a way that helps to mitigate the risks of acting as professionals in public in this way.

To put a button on these things—JITP is a model, I think, for how to build a publishing process that, in form and function, centers student pedagogy. It’s not enough to publish pedagogy or to cite it. Our scholarly structures need to be built and rebuilt with student voices, experiences, and needs in mind. This process is challenging, tenuous, and always in process. For those of us lucky enough to still be here, to be in full-time positions, it’s on us to help the students of today meet the challenges of this work. To help make space for students. To hold the bucket and shovel and dig in. Thanks!