Disrupt the Humanities? (Managing Director job talk)

When scholars share their job talks after being hired, DH and libraries interviewing processes become a little less mysterious. Academia has many genres of presentation. It can be difficult to draft your first job talk without seeing how others in your field translate a job ad’s requirements into a job talk’s expression of their unique expertise. Lee Skallerup Bessette, Celeste Tuong Vy Sharpe, Chris Bourg, and Brandon Walsh all share successful job talks on their websites (I shared the talk for my previous role, too).

I’ve long been a fan of the digital humanities at the University of Virginia, and I’m excited to join the Scholars’ Lab and University of Virginia Libraries teams as Managing Director of the Scholars’ Lab. In this post, I’ll share the talk I presented as part of my campus interview for this role.

The presentation prompt asked for a discussion of my past projects:

The digital has the potential to be a disruptive force in humanities scholarship, giving scholars the means to critique, reimagine, and transform ideas, theories, material artifacts, and even interpersonal relationships. Using examples from your own collaborations with faculty, graduate students, and staff, please discuss how this disruption can be successfully embodied in scholarly inquiry, as well as in the cultivation of people and organizations.

The presentation

My digital humanities is not disruptive.

Disruption can be a force for good, especially against systemic problems. But to my ear, disruptive is not what I want DH to be.

Disruption is inherently non-introspective; you disrupt others, rather than looking hard at yourself.

Disruption can ignore a history of similar work, and the humanities can’t afford that mistake. For example, a movement to make the humanities more public that ignored the fan fiction communities’ existing public humanities—people using the web to improve one another’s close readings and counterfactual interventions—would be deeply flawed. DH has diverse roots in pre-digital humanities scholarship, including highly recognizable non-digital, algorithmic criticism of the kinds Stephen Ramsay explores in his book Reading Machines. We have much to gain by connecting our efforts today to what has worked in the humanities of the past, and to the humanities that also thrives outside academia.

So when I share some of my recent collaborative DH work with you today, I’d like us to consider this work not in terms of how it disrupts the humanities, but through a variety of more positive and generative lenses. DH as…

-

An applied humanities

-

Experimental

-

Public and participatory

-

A radically interdisciplinary humanities, embracing social science, science, and art

-

Open to any challenges to which we can bring our skills of humanities thinking

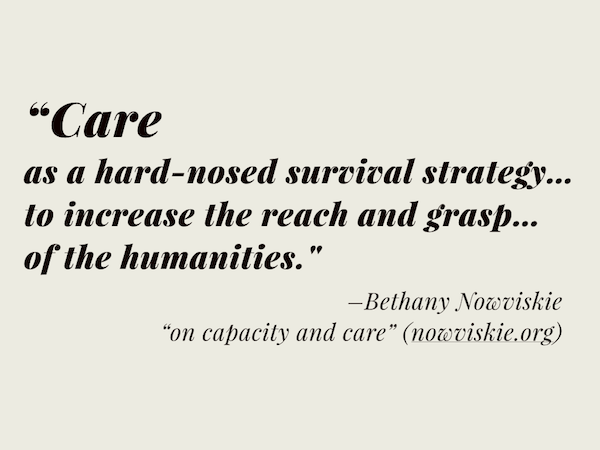

I’m hopeful for the humanities Bethany Nowviskie has imagined in her work “on capacity and care”. Nowviskie cautions: “Please do not mistake [capacity and care work] for something idealistic and motherly and sweet. I offer care as a hard-nosed survival strategy… to increase the reach and grasp (which is at the root of the word “capacity”—the “capture”) of the humanities.”

Seeing both the positive and negative sides of disruption, and turning to other concepts with different values, aren’t only reactions fueled by thinking these are good ways for a person to be in the world. There are significant gains for pushing our scholarship to be more intellectually generous, more locally interconnected, and better at crediting key emotional labor such as team-building and mentorship.

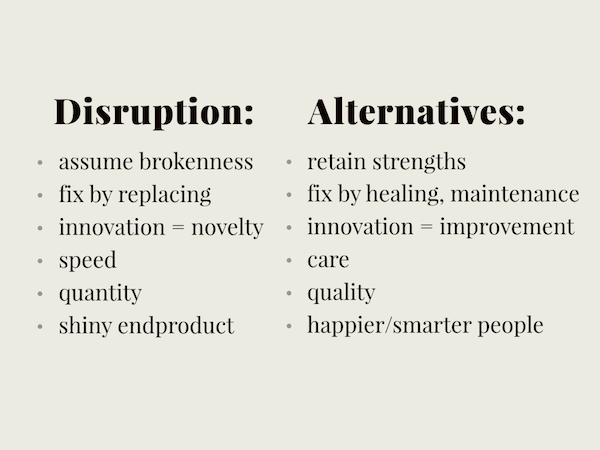

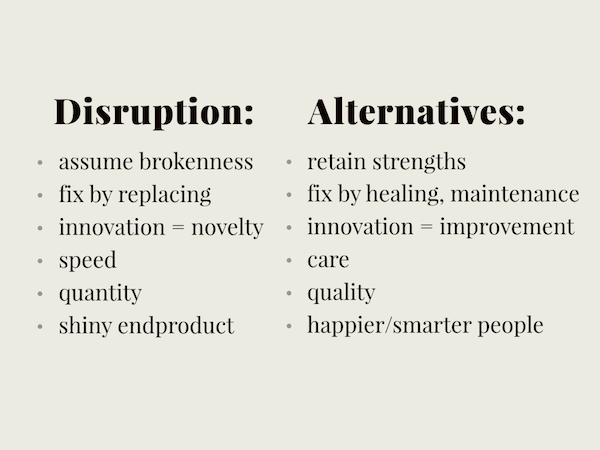

So in the next twenty minutes today, I want to tell you a bit about two of my recent DH projects, one where the bulk of the work is my own, and one where I’m only nominally the creator. This work articulates some of my hopes for what the digital humanities could be, a DH deeply part of the humanities rather than opposed to it, a DH that’s more interested in the right column up on the screen [in the image above this paragraph, for blog readers]—in seeing innovation in maintainance, the quality rather than the quantity of impact, on “people over projects” (as the Scholars’ Lab puts it).

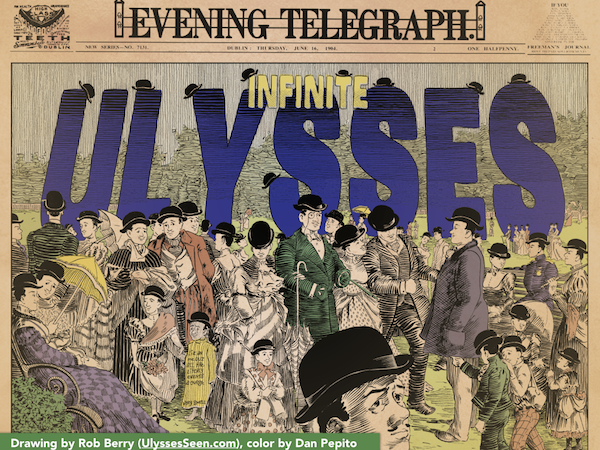

The first project I’ll discuss, Infinite Ulysses, shows humanities scholarly inquiry that’s been reimagined and opened beyond academia, rather than disrupted.

I’m a textual scholar. I decided that instead of focusing on the scholarly editing aspect of digital editions, my skills and interest were more in line with work like that of Alan Galey, whose Visualizing Variation project created code that lets editors of digital editions intervene in their texts in unique ways. Rather than creating a scholarly edition, I focused more on interface design aimed at opening a literary edition to a public audience.

I asked: What if we build a digital edition and invite everyone? What if millions of scholars, first-time readers, book clubs, teachers and their students, show up and annotate a text with their “infinite” annotations (that is, digital marginalia of interpretations, questions, contextualizations, and other comments)? How would we do that, and what would it do to the text and our understandings of it?

I worked through this speculative experiment, with its admittedly unlikely hypothetical of a massive public desire to read Ulysses online. But I also built a prototype that was immediately useful in exploring these questions, through the generous annotations and feedback of an actual, modestly sized community of readers.

Infinite Ulysses (at InfiniteUlysses.com), is a participatory digital edition of James Joyce’s challenging novel Ulysses. Its goal was to support a public conversation about the novel, bringing readers of different backgrounds into participating in the same discussion space. The design, code, usertesting, and thinking that went into this project doubled as my literature dissertation.

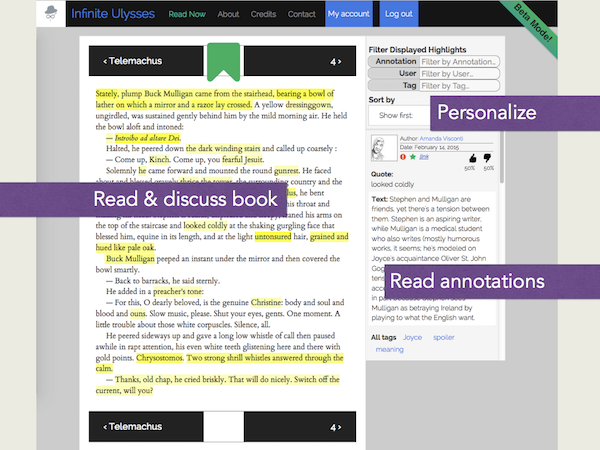

This is what reading a page on Infinite Ulysses looks like. There are three main activities you can pursue:

-

While reading the novel, you can highlight parts of the text and annotate these with your questions, interpretations, reactions, translations, and other comments.

-

You can also read the annotations created by other readers.

-

And I tried, at a basic level, to personalize your reading experience by filtering the displayed annotations so that you could just be shown the ones that fit your needs, interests, and background. For example, a reader can choose to see the top-rated annotations first, or the newest annotations; or to not see any spoilers; or to only see annotations tagged as clues to the book’s mysteries, references to Irish politics, or jokes you might miss.

There is some solid interest in this approach. My work was cited in The New York Times this past summer, drew around 13,000 unique visitors in its first month of beta testing, and drew over 25,000 unique visitors during its beta year (April 2015-2016), despite little intentional publicity after the first month. I share these numbers to show that there’s interest in this scholarship, but in doing so I feel uncomfortably close to getting caught up in the allure of large-scale impact.

Much more important to me, and to the humanities, are the far smaller number of people who actually repeatedly visited and annotated Ulysses on the site. What matters is the students who hear about my dissertation and are encouraged to also pursue the most appropriate methods for their research questions. I care about my impact at the scale of individual readers, like the South Korean reader who found my edition more accessible for her translation and understanding. Or the 90-year-old retired man who wrote that he’d always wanted to read Ulysses, and now he felt like he could take his laptop to a bar, pull up a stool, and maybe actually read the thing this time using my site.

There are other facets to the scholarship of Infinite Ulysses, clear areas of research inquiry:

My 1st research question was an interdisciplinary DH one:

How can we design digital editions that are not just theoretically accessible to the public, but invite and assist public participation? And are there ways to design for meaningful public participation in literature, that don’t require the public to learn scholarly rhetoric?

My 2nd question was from the field of information science:

How can we design public DH websites to handle a huge influx of readers and annotations, so that individual user experience doesn’t suffer and diverse user needs are met? How would each user find the “signal” of the best annotations for them to read, from the noise of “infinite” public annotations?

My 3rd question was from the field of literature:

Textual scholars often create editions as their scholarship. By separating out historical textual scholarship values from how the editions realizing those values looked, can we imagine other forms still holding true to the values of our field? What can we learn by accepting scholarly editions as just one of many ways of embodying textual scholarship values?

Now, I’m here to speak about collaborative DH today, and you might be wondering how a literature dissertation can be a collaborative rather than a largely solo activity. I did perform the full scholarly labor you’d expect from a literature dissertation—most people would agree successfully defending the dissertation and becoming a tenure-track assistant professor shows that. But beyond my dissertation-length work, the larger project around my dissertation relied strongly on collaboration and the intellectual generosity of others.

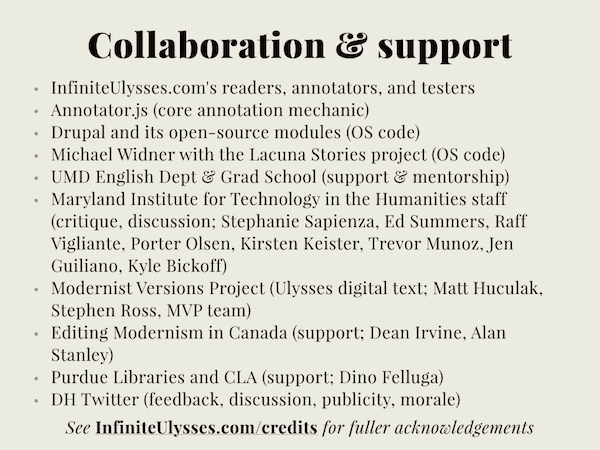

A huge number of people made Infinite Ulysses possible, so much so that I can’t name everyone right now, but I’ve put as many as possible up on the screen [image above previous paragraph, and this credits webpage goes into more detail].

My advisor Matt Kirschenbaum and committee members Neil Fraistat, Kari Kraus, Melanie Kill, and Brian Richardson are amazingly intellectually generous scholars. They met with me as a team regularly throughout the entire dissertation, which was hugely helpful in keeping everyone informed about and happy with the developing look of the dissertation. I also benefitted from the feedback of colleagues at the MITH DH center where I worked 2009-2015, such as Stephanie Sapienza and Ed Summers. Their questions, guidance, and encouragement were critical in realizing my project.

Through social media, DHer Michael Widner at Stanford and I discovered we were working on similar tech (the Drupal annotator module). Despite being on opposite coasts, we Skyped to discuss our work, and he ended up generously allowing me to build on top of some of his Lacuna Stories project code that hadn’t yet been publicly released, allowing me to spend more time on a different piece of coding more closely tied to my research questions.

The people who visited Infinite Ulysses and shared annotations and/or feedback on the site are collaborators, too. The majority of the site’s annotations were authored by people other than me. Ten types of user testing, data gathering, and participatory design, with a variety of people, over the course of the site’s development, directly shaped the growth of the site.

Infinite Ulysses was a collaborative project with a large portion created by one person. Now, I want to tell you about a project that’s far more of a distributed and balanced collaborative, the Digital Humanities Slack.

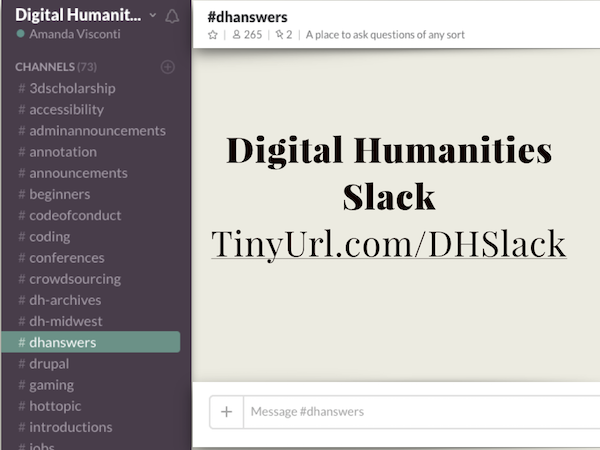

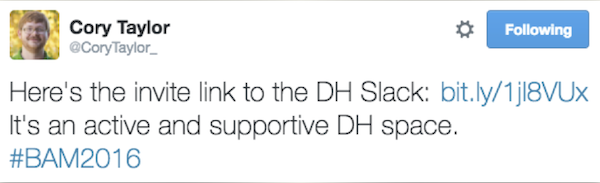

Slack is a social media platform that functions like a set of interconnected, themed chat rooms. Using the Slack platform, I created and manage the scholarly forum of the Digital Humanities Slack (or DH Slack). Started a little over a year ago, it now supports over 1,200 digital humanists through around 70 “channels” (thematic chat rooms on topics like libraries and the digital humanities, open access, data sharing, and various DH methods and theories).

The DH Slack is open to anyone with a curiosity about DH and/or related interests (e.g. digital libraries, museums, and archives)—those interested just visit tinyurl.com/DHslack to join. Absolutely no DH expertise is required, and we have several specific channels devoted to DH beginners, students, job seekers, and asking all kinds of DHy questions.

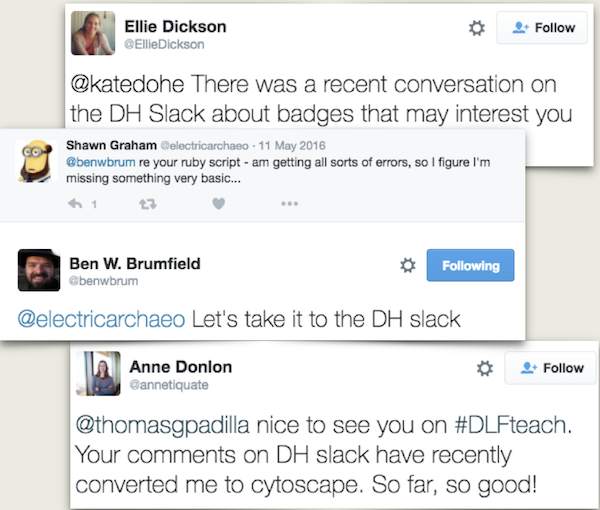

The DH Slack is ““mine”” [all the air quotes] in an extremely limited sense, if any. I set up the Slack, publicize its existence, moderate it, periodically started discussions (more in its early days than now), answer questions about using the Slack, and lead policy-making such as adapting a DH-specific code of conduct. That code of conduct covers things like not publicly posting screenshots of Slack conversations without first getting the consent of everyone shown in the shot, which is why I’m largely showing tweets rather than screengrabs.

Five other DHers generously collaborate with me as additional Slack moderators: Alan G. Pike, Sam Abrams, Alex Gil, Ed Summers, and Paige C. Morgan. We take our code of conduct seriously, and have taken firm action when it’s been called for, to protect our community members.

The DH Slack exists because of its members, who build a humanities community through their conversations and sharing. Even the most collaborative and democratic of teams needs one person to really be in charge of project management, and I feel like my current role with the DH Slack is similar—helping things along, being available and responsible should problems arise, and making the final call after group discussion.

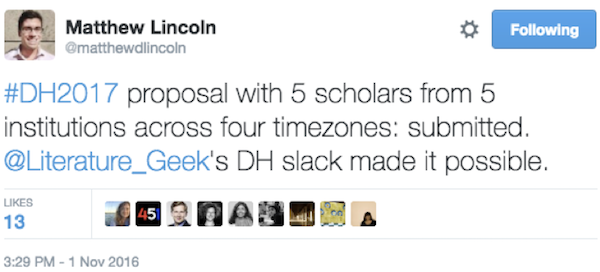

We’re still figuring out how Slack can be useful to our scholarship: Can it allow different kinds of conversations than Twitter? On the screen, you can see examples of DHers moving between the Slack and Twitter to have different kinds of conversations—in that middle tweet, a technical discussion that was limited by Twitter’s format switched to the Slack to continue more freely.

Some of our members work at non-profits or in K-12 teaching, or aren’t professionally involved in academics; some are undergrads or grad students. It’s clear that the Slack, like many other platforms, can support geographically dispersed collaborators. But can we use the Slack to teach and support people interested in DH who don’t know of any potential collaborators, don’t have mentors geographically near them, or who aren’t inside academia? For example, I’m hoping to do a Slack hangout this spring where I’ll be available on the Slack to help anyone who wants to work through my Programming Historian lesson on creating their own first research website. If DH mentors can periodically be virtually available to support questions about specific tech tutorials, maybe we can ease new DHers experimentation with digital methods.

Interesting uses of the DH Slack I’ve seen so far include allowing remote participants at MITH’s recent “Night Against Hate” scholar-activist hackathon, mentorship for new digital humanists, a place to connect regional DH networks such as in Tennessee, Baltimore, and Australia and languages such as Spanish, and as a space to expand Twitter conversations. We’ve been used as a model by other scholars for their own Slack instances, and I authored an invited guest post about the DH Slack for the London School of Economics blog this past summer. If you’d like a place to discuss and learn about the digital humanities, or a friendly place to ask questions, please join us via TinyUrl.com/DHSlack.

Both the DH Slack and Infinite Ulysses model a digital humanities that’s not disruptive, but different. Both take an experimental approach grounded on past humanities successes, whether that’s DH Twitter or speculative textual experiments like the Ivanhoe game or Prism. The experiments of both projects recognizably demonstrate humanities scholarship and community.

Both experiments also demonstrate my key interests. I’m deeply invested in DH design and building as a route to new knowledge, especially through interfaces for public, communal learning. And I’m keenly interested in the larger questions of how we make DH go: infrastructure and process, project management, and community-building. If you visit my LiteratureGeek.com blog, you’ll see that I share everything from theory and analysis, to my software and design decisions, how I get started planning a new project, and how my work space is set up. This is all as a way to think through not just the strategies, but also the daily tactics of successful DH.

Infinite Ulysses and the DH Slack are at two ends of the collaboration spectrum, but the bulk of my interdisciplinary collaboration experience actually happens quite differently, in project teams that regularly meet face-to-face (as with a group of graduate students I taught to work with the Shelley-Godwin Archive) or over Skype (as with the BitCurator team).

For example, in my current role as a DH librarian and faculty at Purdue Libraries, I enjoy a close working relationship with my colleagues in both Archives and Special Collections, and in our university press. Together, we’re using DH as the connector to build a workflow for campus DH research and teaching that runs from archival description and discovery, through scholarly communication and publication.

I didn’t cover this kind of collaboration in detail in this talk, as I suspect this kind of face-to-face collaboration is the most common and familiar. But, I’ll wrap up by listing on the screen a few of my more typically collaborative DH projects on the screen, and I’m happy to discuss these further in the Q&A or over email.

Originally posted at LiteratureGeek.com. Edited 3/6/2017 to link to Brandon’s job talk.