BESSing With Collective Biographies of Women: Identifying Our Own Misconceptions of the “Fallen Woman”

As a research assistant on Alison Booth’s Collective Biographies of Women, I have come to understand how the quintessential “angel in the house” reigned supreme within many women’s biographies. This concept of the “angel in the house” emerged primarily through 1830-1890, conveniently when some of these biographies were being published. It then serves as no surprise that the trope of the “angelic” woman can quite easily be identified as these biographies were published from 1830-1940. Even the very word, “angelic,” appears 701 times in the sample textual corpus in CBW. However, it arguably becomes more fascinating to note those women who did not “fit” into this stereotypical mold. Upon reflecting on my own “BESSing” experience, I began to reanalyze previous biographies I had been assigned—specifically those in the collection Feminine Frailty. I was expecting myself to agree with the ascribed “Persona Descriptions” I had given to each woman, knowing that only a few weeks had passed since the completion of these biographies. Instead, I found myself questioning the author’s discourse and my own subjectivity that led to me characterizing these women.

With the women I have BESSed, there emerges contention of how we label women who are more “modern” in their acceptance of sexual desires, but also those women who are the victims of sexual assault. It becomes a challenge for the BESSer to be critical of our own interpretations, as we are not only susceptible to the author’s discourse, but are just as likely to be part of the system that unfairly characterizes such women. Even as 21st century readers, we perhaps more openly admire those women who remain in the domestic sphere and maintain monogamous relationships. Meanwhile, women who illustrate their “sexual deviancy” are likely to be considered as disreputable or dangerous, thus garnering no sympathy when they are taken advantage of.

As RAs for CBW, one of our main concerns is using an XML schema to tag many of the biographies in the CBW project. The XML schema used is known as “BESSing,” which stands for Biographical Elements and Structure Schema. BESSing can further be explained in Lloyd Sy’s introductory blog found here.

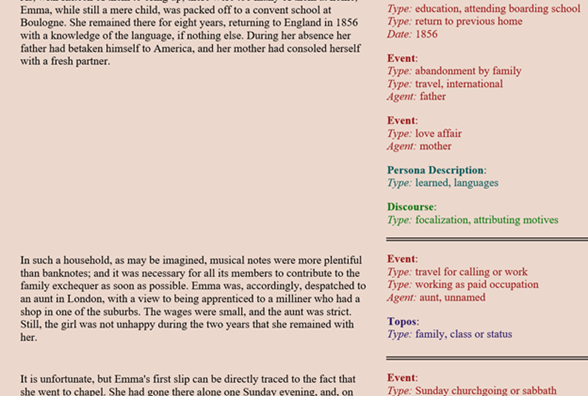

Looking below, one can understand just how these biographies look when the XML schema is applied and what tags are applied by a “BESSer:”

This screenshot is taken from the collection Feminine Frailty and surrounds the biography of Emma Crouch, otherwise known as Cora Pearl. Cora Pearl, alongside Mary Anne Clarke and Madame Roland, are the subjects of this blog. All three women are notable in their reputations, however both Pearl and Clarke are likely to be only noted as using their “sexual deviancy” to their advantage and rising in society. Meanwhile, Roland is exemplified as the “angel of the house” and cited as a patriotic, dutiful mother and wife–to which readers of her biographer could openly aspire to be. For the purpose of this blog, I aim to draw out how our own subjective interpretations often come into play in BESSing.

As CBW BESSers, we are often assigned multiple biographies that involve one individual. This allows for the CBW BESSer to recognize how multiple authors differentiated biographies of the same person. For example, in CBW the French revolutionist, Madame Roland, is either the primary subject or a secondary subject within 35 biographies. While some biographers may expose her early childhood, other biographers may begin her biography at the start of the French Revolution.

However, as BESSers we are also assigned bios within a single collection. BESSing the biographies in the collection, Queenly Women, Crowned and Uncrowned, allows for a CBW editor to analyze how the biographer characterized women belonging to nobility, as well as middle-class women who exemplified queen-like qualities, such as Madame Roland. By BESSing multiple biographies from the same author, a RA is likely to recognize similarities that characterize each biography, such as each version beginning in the early stages of the woman’s life or the author using repeated discourse forms, like “direct address, use of I or one.”

I have been assigned biographies of Madame Roland from two collections: A Book of Noble Women and Heroines That Every Child Should Know: Tales for Young People of The World’s Heroines of All Ages. From both biographies, Madame Roland is painted in a favorable light and while she is a revolutionary heroine known for her achievements “outside” of the home, she too embodies the qualities that make up the “angel in the house.” In Heroines That Every Child Should Know, the editors go so far as to credit Madame Roland with such favorable qualities as a “young and beautiful wife so devoted to [her husband]” that “she sought only to elevate [his] position and expand [his] celebrity” by writing many of his works. As she was the “perfect housekeeper” who “idolized” her young child, Edora, it serves as no surprise that Madame Roland’s ‘Persona Description’ contains tags like ‘dutiful,’ ‘self-sacrificing,’ and ‘maternal or nurturing.’ (I don’t mean to describe Madame Roland as a woman who sat idly by in the comfort of her home solely focused on her family, but it becomes interesting to note how the editors pay such fastidious attention to her wifely duties and housekeeping accomplishments.)

In many of these biographies, one can’t help but note how women were set up as faithful servants to their husband and even country. However, examining the collection Feminine Frailty by Horace Wyndham, I would like to propose how difficult it can be to “BESS” women who were believed to belong to the lowest rungs of society. These “fallen women” I would argue demand critical interpretations for how the author characterizes them.

Unintentionally, we may find our own subjective impressions and prejudices arising upon BESSing such “fallen” biographies, and this is further strengthened by the author’s discourse. These issues complicate how we attempt to personify and classify women in CBW. Many women who fall into the “angel in the house” category, like that of Madame Roland, can easily be credited as “positive” figures just by simply drawing similarities between “Persona Description” tags found within her multiple bios. However, there emerges complications of how we attempt to classify and personify women who are more likely to fit into the “fallen women” category. Such women were likely seen as sexually disreputable, adventurous, calculating, and reckless in their actions. Exploring Cora Pearl (Emma Crouch) in Feminine Frailty best exposes these complications of a BESSer’s decision in personifying a woman who, although considered “fallen,” was more the victim of circumstances. Questioning and evaluating the “Persona Description” values that editors have tagged leaves one wondering how our own personal values unconsciously come into play.

Reading Cora Pearl’s biography, one learns that she belonged to a large family with over 15 siblings. There was never steady income, as Cora’s father abandoned the family to emigrate to America, so Cora was sent to work as an apprentice at a young age. A reader quickly understands how these adversities led to Cora Pearl’s “first slip”—as Wyndham characterizes it. Walking alone one night from a chapel, Cora is approached by a young man and the topos “youthful desire for love” quickly comes into play. She accepts his invitation to a “sordid, flashy establishment, full of odd-looking people.” Cora unknowingly accepts a laced drink and awakens to find herself having been sexually assaulted by the man. He only laughs before giving her a £5 note and “coolly [tells] her to go back to her aunt.” Shame and disgust can be ascribed to Cora’s feelings and she knows that returning home is not an option for fear of how she will be received.

Rereading these brief passages a second time, I question how I BESSed Cora as “naïve” and “reckless” in multiple passages and whether I would choose these descriptions upon a second BESSing. Upon looking through “Persona Description,” I noticed recurring tags that left me questioning my BESSing:

- “Reckless”— (4)

- “Naïve”— (5)

- “Flawed”— (5)

- “Greedy or Mercenary”— (7)

After identifying these tags, I began to examine the biographer’s language that had resorted to me classifying a victim of rape and sexual assault as being “reckless” and “naïve.” By extracting and analyzing various, fragmented descriptions of Cora, I came to unveil how these tags were applied: “It is unfortunate, but Emma’s first slip can be directly traced to the fact that she went to chapel…Forgetting the lessons of the convent, and the sermon to which she had been listening, and only remembering the dull suburban home that was awaiting her.” Examining these two sentences, Wyndham is characterizing Cora as a woman who forgets her religious teachings in favor of something exciting. This leaves a BESSer to draw the conclusion that perhaps Cora is naive and reckless. It is right after leaving the chapel service that she falls prey to a “well dressed, whiskered gallant [who] knew how to make himself agreeable.” Her willingness to accompany a persuasive stranger (who has nothing but sordid thoughts on his mind) and thus being the victim of rape is merely titled as the heroiene’s “first slip.” The biographer lessens the severity of what has happened to Cora with this description, and the BESSer is led to interpreting this as just one of Cora’s many self-induced acts of violence. She later chooses to rename herself from Emma Crouch to Cora Pearl to better assimilate into France. The author cites this as “another step on the downward path she had deliberately elected to follow.” The act of renaming herself is “another step” in tarnishing her character and furthering herself from the 15 year old girl who had once left the chapel.

Upon noticing these “Persona Descriptions” of Cora Pearl in Feminine Frailty, I found myself searching through other biographies in the collection wondering if any other heroine with similar circumstances was given tags of “reckless” and “naive.” Coming across Mary Anne Clarke’s biography, she is typified as a “fallen woman” much in the same manner as Cora. Although not the victim of sexual assault, I wondered if the same “Persona Description” tags found in Pearl’s biography had been carried over to Clarke’s. In Clarke’s biography, there are similar “negative” “Persona Description” tags form Pearl’s biography, however there are also “positive” tags that are nonexistent in Pearl’s biography:

- “Persuasive”— (5)

- “Clever”— (7)

- “Naïve”— (3)

- “Flawed”— (2)

- “Greedy or Mercenary”— (4)

Unlike Cora Pearl, Mary Anne Clarke is framed as a clever and calculating woman with no attributes of “recklessness.” We also see how “greedy or mercenary”, “naïve”, and “flawed” are less attributed in Mary Anne Clark’s bio—despite her using her relationship with the Duke of York for bribery and to collect payment from notable men to fund her lavish lifestyle. Quantifying the “Persona Descriptions” and attempting to justify these attributes leaves me with the conclusion that a BESSer often unknowingly perceives a persona in a positive or negative light (even if that persona’s circumstances demand sympathy and understanding) based on the author’s language. This serves as a reminder of how powerful discourse can be.

I now ask myself such questions as:

Is it solely the author’s discourse or does a BESSer’s own subjectivity come into play (even unconsciously) when labeling women with such negative and positive “Persona Description” tags?

Unlike early 20th-century readers, who likely agreed with Wyndham’s characterization of Cora Pearl as “reckless” and “naive,” are 21st-century readers persuaded by Wyndham’s depiction or is it easy to recognize Cora as the victim of circumstances?