First Steps with NLP and a Collection of Amiri Baraka’s Poetry

Amiri Baraka’s Black Magic, 1969

In this post I’ll discuss my initial foray into natural language processing (NLP)—cleaning up a corpus and prepping it for some basic text analysis techniques. I want to begin, however, with a note on the small textual corpus that I’m using in these preliminary explorations—Black Magic, a 1969 collection of three books of poetry by Amiri Baraka.

In a prefatory note to the collection, Baraka offers an “Explanation of the Work” that touches on the three books of poetry contained within. “Sabotage,” he writes of the first book, “meant I had come to see the superstructure of filth Americans call their way of life, and wanted to see it fall. To sabotage it,” in a word. The second book, he argues, takes this intensity even further: “But Target Study is trying to really study, like bomber crews do the soon to be destroyed cities. Less passive now, less uselessly ‘literary.’” If these comments are any indication, the poetry of Black Magic has a certain level of emotional and political intensity. These poems articulate rage—they thunder, fulminate, and protest, venting a vindicated anger at racial injustice in America. Others simmer with a more restrained heat, but still tend to employ an often unsettling rhetorical violence. Consider, for example, the conclusion of a poem from Sabotage titled “A POEM SOME PEOPLE WILL HAVE TO UNDERSTAND”:

We have awaited the coming of a natural

phenomenon. Mystics and romantics, knowledgeable

workers

of the land.

But none has come.

(repeat)

but none has come.

Will the machinegunners please step forward?

Though startling, this final image punctuates a familiar narrative: the mounting of frustration, the boiling over of feeling while waiting and waiting for justice. The speaker’s closing remark seems to respond to the question asked in Langston Hughes’s poem “Harlem”—“What happens to a dream deferred?”—but raises the ante of the inquiry, and shifts from Hughes’s suggestive but still open-ended conclusion (“Or does it explode?”) to an unsettling direct request (“Will the machinegunners please step forward?”). The poem also, however, seems aware of its high dramatic tone: it conveys the gravity of this deferred deliverance with somewhat formal rhetoric like “We have awaited” and “But none has come”, but highlights—and perhaps undercuts—its own theatricality by embedding a stage direction in the poem, “(repeat)”. We’ve waited for long enough, the poem seems to argue, but stages this claim in such a way that the final line’s delivery hangs suspended somewhere between deadpan and dead serious.

In short: a heightened revolutionary rhetoric permeates the poems in this collection. Many have noted, however, that a troubling violence permeates them as well. For example, one scholar describes “Black Art”—one of the most graphic but also most well-known poems from this collection—as “a difficult poem in its race and gender violence, in its violence against peoples.” In the 1991 The Leroi Jones/Amiri Baraka Reader, editor William J. Harris describes Black Magic as a collection in which Baraka “traces his painful exit from the white world and his entry into blackness,” an “exorcism of white consciousness and values [that] included a ten-year period of professed hatred of whites, and most especially jews [sic].” Baraka looks back at this period in his 1984 autobiography at a remove from the red-hot intensity of the poems themselves: “I guess, during this period, I got the reputation for being a snarling, white-hating madman. There was some truth to it, because I was struggling to be born, to break out from the shell I could instinctively sense surrounded my own dash for freedom.” From this perspective, this is the violence of escape, of “struggling to be born” from within a constricting “shell”—a version, perhaps, of the violence of the deferred dream that explodes at the end of Langston Hughes’s poem “Harlem.”

Initial Steps with NLP

As a scholar interested in articulations of anger, resentment, and frustration with injustice—particularly injustice of a systemic and institutional nature—as well as digital methodologies, I thought these texts in particular might be worth looking at more closely with NLP techniques.

As a graduate student working in a period that is almost entirely still in copyright, however, Black Magic also interested me because it is a small corpus of works—three books of poetry—to which I currently have access through UVA. Though conceptually unglamorous, basic questions of access have played an enormous role in determining the initial paths in my scholarly decision-making process.

In this sense, though assembling workable data is always a challenge, scholars interested in literary texts prior to the early 20th century have more options for readily accessible textual corpora. For 20th- and 21st-century scholars interested in textual analysis, however, questions of copyright have made finding openly available textual data from which a corpus could be built an extremely difficult task: while able to share results of analyses through transformative, non-consumptive use, scholars of these periods cannot share the corpora from which these insights are drawn. This presents additional challenges in terms of reproducibility as well as in the already long, labor-intensive task of assembling, cleaning, and prepping a corpus prior to any actual application of NLP techniques. If texts aren’t already available as text files through a university or institution, they either have to be typed out by hand or scanned page by page, run through optical recognition software that transforms the page image into text, then also ultimately cleaned and corrected by hand. In short: no preexisting corpora means no experiments, prototypes, or conceptual ventures without surmounting certain barriers to entry that often prove time- or cost-prohibitive.

In the case of this project, even though UVA has access to the 1969 edition of Black Magic: Collected Poetry 1961-1967, the text isn’t ready for NLP out-of-the-box. The page contained a lot of text beyond that of the literary work in question: page numbers, line numbers, bibliographical information, headers and footers, all kinds of weird punctuation, and so on. For example, the title of the first poem in Sabotage, “Three Modes of History and Culture,” appeared in this electronic edition as follows:

Baraka, Imamu Amiri, 1934- : Three Modes of History and Culture [from Black Magic: Collected Poetry 1961-1967 (1969) , The Bobbs-Merrill Company ]

To perform sentiment analysis on Sabotage, then, I first needed to get the raw text. By “raw text” I mean a big bag of all of Sabotage’s words. My goal initially was to get this bag of words with no line numbers, no punctuation, no capitalized first letters (otherwise Python would think they were two different words), and no spaces.

As someone doing this work for the first time, I felt like I could handle writing a program that would remove capital letters, get the txt file into the correct file-type, maybe even get rid of the line numbers. But what about all this clutter surrounding the title of each poem? I considered how I might remove this with a program, but even something as small as irregular line breaks means the words would be chopped up in slightly different ways each time. Given the size of the corpus, I decided it would be wiser to remove the clutter by hand than to write a one-time program that automated it.

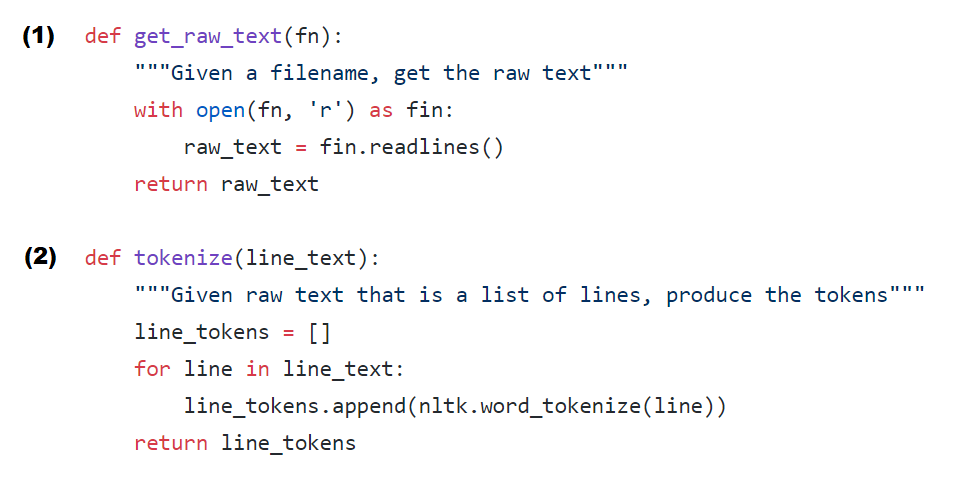

With a huge assist from Brandon Walsh, cleaning up the rest of the text with the Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK) was relatively straightforward. We wrote a small Python script that removed line numbers, then proceeded to write a script that would prep the clutter-free text files for text analysis, first by reading the text file as a list of lines (1), then by tokenizing that list of lines into a list of lists, where each sub-list is a list of the words that make up a line (2).

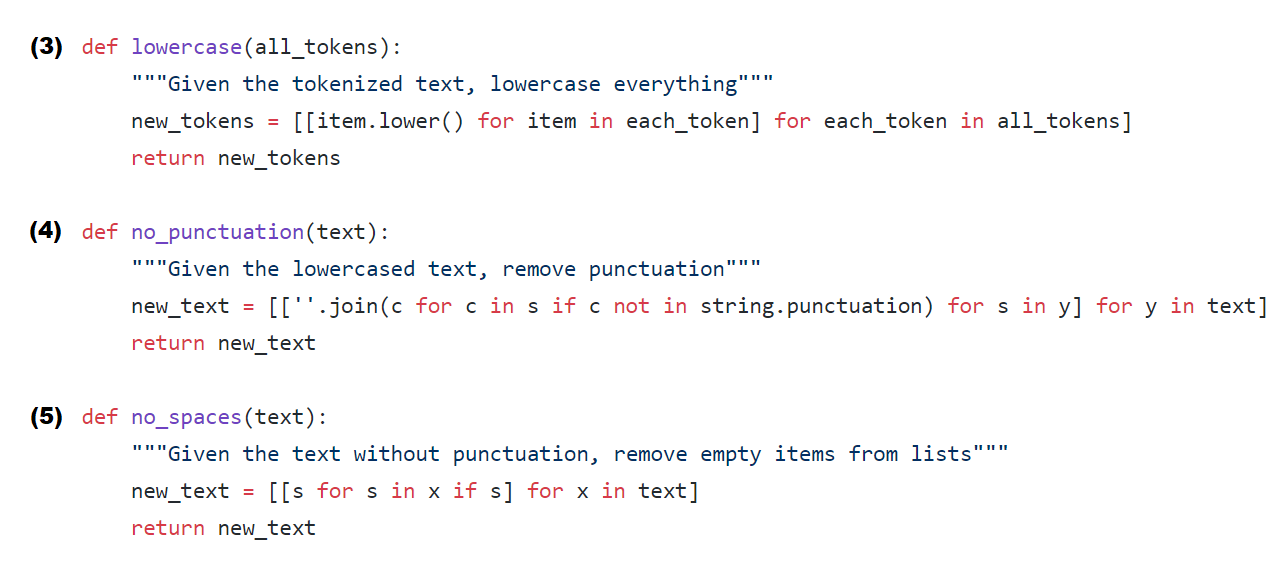

While this may seem kind of complicated, certain kinds of text analysis need the lines to be tokenized in this way—much of the work then involves getting the text to be the right kind of data type (list of words, list of lists, etc.) for a given kind of analysis. Because I’m interested in sentiment analysis, I also needed to make every word lowercase (3), remove punctuation (4), and remove spaces (5).

While this may seem kind of complicated, certain kinds of text analysis need the lines to be tokenized in this way—much of the work then involves getting the text to be the right kind of data type (list of words, list of lists, etc.) for a given kind of analysis. Because I’m interested in sentiment analysis, I also needed to make every word lowercase (3), remove punctuation (4), and remove spaces (5).

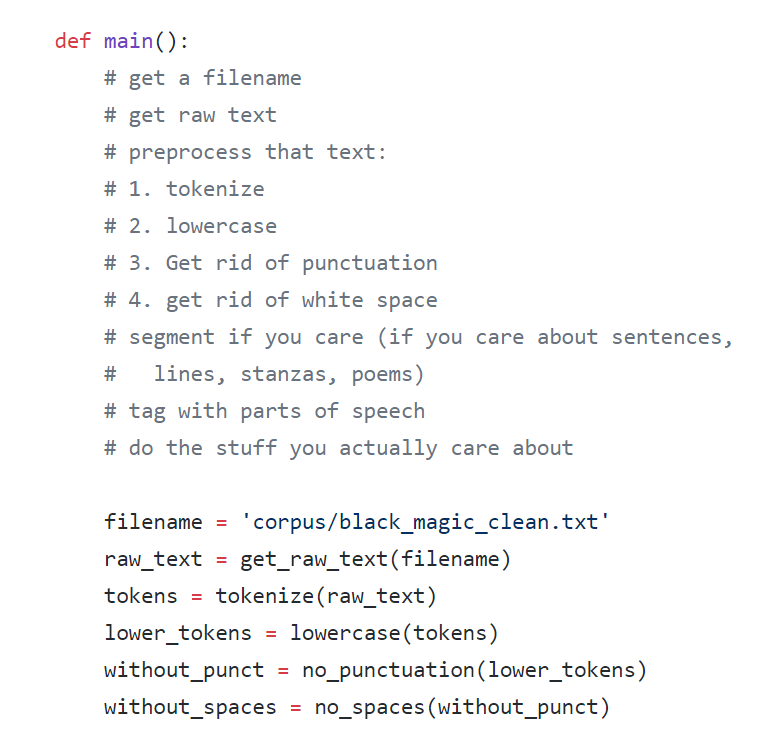

Having written out all these functions, we then made a new function that called on each of them one after the other, running through the pipeline of activities necessary for NLP (our notes-to-self included):

Though it gets the job done, this code is clunky. It represents, in short, the first steps in my learning how NLP works. And while not the most elegant in terms of form or function, writing steps out in this way was conceptually clear to me as someone trying them for the first time. I also want to add that throughout much of this Brandon and I were practicing something called pair programming, with Brandon at the keyboard (or “driving”) and me observing, asking questions, and discussing different ways of doing things. In addition to being an exciting scholarly investigation, this project is also a learning experience for me, and our code-decision-making process often reflects that.

But more on the intricacies of collaboration later. To recap, at this point I had a series of functions that, in a linear, step-by-step fashion, took my original text file and began to play with them in Python’s working memory: it took Amiri Baraka’s poetry as one data type (a giant string of words) and turned it into another (a tokenized list of lists), with some changes along the way (like lowercasing and getting rid of punctuation).

What made this so clunky, however, stemmed in large part from how I had organized my tasks: I gave Python basically only one thing to think about and work with at a time. It would take my corpus, W, and turn it into X, which it would then turn into Y, and then Z, and so on. But if I wanted Python to remember X while it was working on Z, I had to write code to turn Z back into X—in short, a data-type nightmare. Which sounds pretty abstract, but presented all kinds of practical problems.

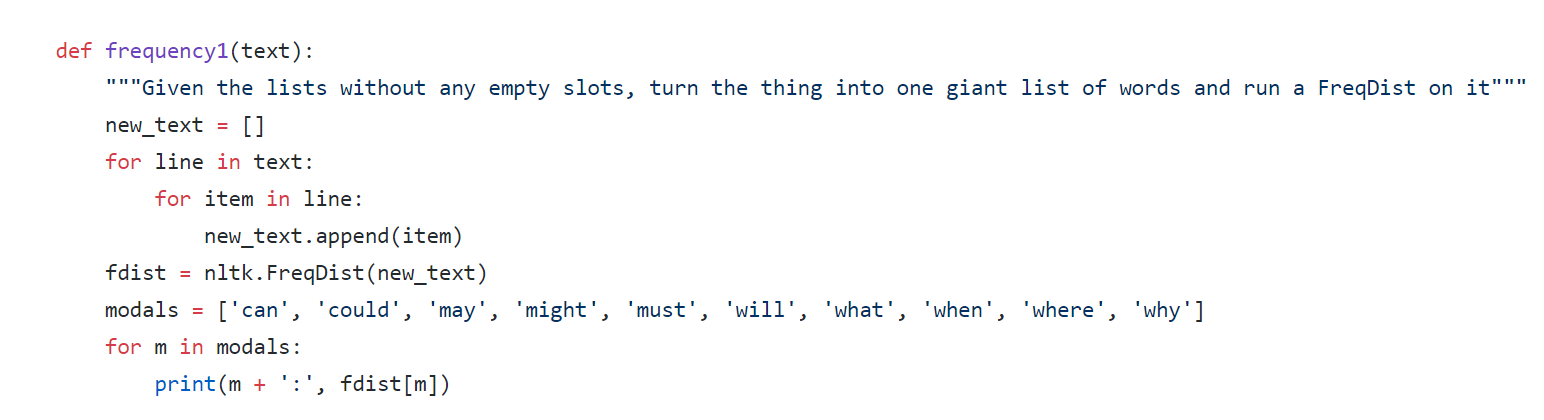

For example, after having gotten all the way to Z—my lowercased, punctuation-free list of lists—I wanted to try a basic form of text analysis I had seen in an early chapter of the NLTK book (called stylistics) in which I compared the use of different modal verbs in the three books of Baraka’s poetry. The only way I knew how to do this was to run a frequency distribution on a giant list of words—which means I had to un-tokenize my nicely tokenized texts, basically jumping from Z back to W. So I wrote some clunky code that let me do so:

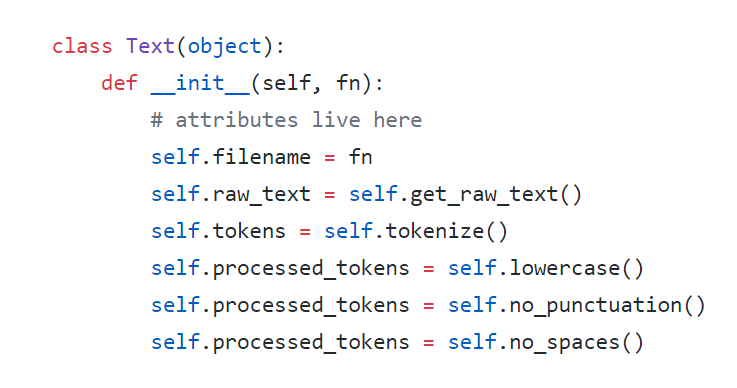

Grappling with this problem, Brandon re-introduced me to something I had learned about before but never had to use—object-oriented programming. Rather than performing a linear series of functions on my text file, reorganizing my code along OOP lines let me treat this text file as an object with many attributes, any of which I could access at any time. If I wanted my file (or object) as a giant list of words to perform a frequency distribution, I needed only to call upon that particular aspect (or attribute) of my object. If I then wanted Python to think of it as a tokenized list of lists I could just call on that particular attribute rather than having to send it through a series of transformations. It’s as if my ability to manipulate a file gained a third dimension— instead of begin stuck going from X to Y to Z and then back to X, I had access to all three stages of my file simultaneously. In essence, what was once a one-way data-type conveyor belt now became a fully-staffed NLP laboratory. In another pair programming session, we started to shift my more linear code to an object-oriented approach. What we came up with definitely needs refactoring (in my TODO list) and can certainly be improved (i.e., not overwriting a variable multiple times), but again, in the spirit of showing my learning process, I wanted to share a visual of this early version that marked my beginning to grapple with OOP for the first time:

Finally “getting” object-oriented programming conceptually was truly a programming awakening for me, even if my initial attempts need some improvement—it hadn’t really made sense as an approach until I was faced with the problems it helps address.

So we have the poems in all their fiery intensity, as well as the beginnings of actually using sentiment analysis as another way of thinking through them. As it currently stands, Brandon and I have started using TextBlob to perform some basic tasks—more on that soon. If you have any questions or want to follow along, my GitHub project repository can be found here.