GIS Mapping Taught Through the Theory of Accompaniment

Geographic Information System (GIS) mapping attaches a dataset to a specific space and place, substantiating a relationship between the two as not only directly related but as affected by or moved to that specific point on a map. However, when thinking about how to teach a workshop on mapping to a group, one problem came to mind: we are in a generation with a profound lack of relationship to and with maps and the locations of countries. Which, in general, is its own point of discussion; however, when considering migration and mapping, a recognition of this lack became a focus for me. The question formed: how do I first get people not only to see, but really understand this non-relationship?

As students, we shape our own archives, perceptions, and pedagogy through the scholars we read and encounter. The scholar whose work inspired this very workshop, and answered the questions I wrestled with, is Ana Patricia Rodriguez. I was guided through my approach by both her first monograph, Dividing the Isthmus: Central American Transnational Histories, Literature, and Cultures, and her article, “The Art of (Un)Accompaniment: Salvadoran Child Refugee Narratives in the Twenty-first Century.” (10 out of 10 recommend others read both)

First The Non-Relationship

Rodriquez begins her monograph’s introduction with an activity she runs in her classroom. I pull that activity and use it as my own introduction to not mapping, but maps. The assumption I make is clear- Latin American countries do not and will not register as located within the group’s imagination. The lack is made evident. Now, no spoilers, go read her book. This part of the workshop will use 3D-printed or woodcut materials, is theoretically brief, and allows me to transition from map to mapping by asking them questions. I don’t know what I will ask quite yet, but they will be fantastic questions.

Accompaniment as Pedagogy

Next point of inspiration. First, the question. How can I make a GIS mapping workshop interactive and include a dataset based on migrant experiences in Mexico? Rodriguez’s article introduced me to the work on accompaniment. In this article, her reading of Javier Zamora’s Unaccompanied (also a book everyone should read), theorizes “a poetics of un/accompaniment” where,

The poems create a path of accompaniment of critical empathy for readers to follow literally and literarily the migratory routes of child migrants … It is in this process of accompaniment that readers are positioned, if not prodded, to question the conditions that produce child migration and the legal violence of migration policies, which shape the outcomes of arrival, detention, exclusion, and deportation, especially for women and children.

The accompaniment that Rodriguez traces in Zamora’s works and literature builds on scholarship and research on accompaniment in movements and research, but ties it to migration. Poetry and narratives create a different space for “readers to follow” migrants on their route to the United States. This, along with the ways readers are “positioned, if not prodded, to question the conditions,” prompted me to consider how a hands-on GIS workshop almost inherently, and unintentionally, seeks to enact an accompaniment. This is not to claim that there is a perfect or unflawed relationship between mapping and accompaniment. The accompaniment will shift a bit in its movement to the digital and/or in the making of narratives into data points. However, through accompaniment, what became clear was that what I considered to be simply an inherent relationship between place and data was flawed when I maintained it as inherent rather than as something to be questioned and interrogated.

The reality is that datasets can risk reducing humans to bodies in the very act of transforming information into points plotted on a map. That risk is exacerbated when the lack of relationship to a map is already present, and all a viewer intakes is a map filled with marks, even when they attempt to filter and narrow the scope of what they are looking at. With that, can embedding the mapping of points as a process of accompaniment shift how a viewer or a mapper processes a large, complex dataset? And is this shift my pedagogical framework? No clue, I will get back to you on that one.

The Actual Workshop

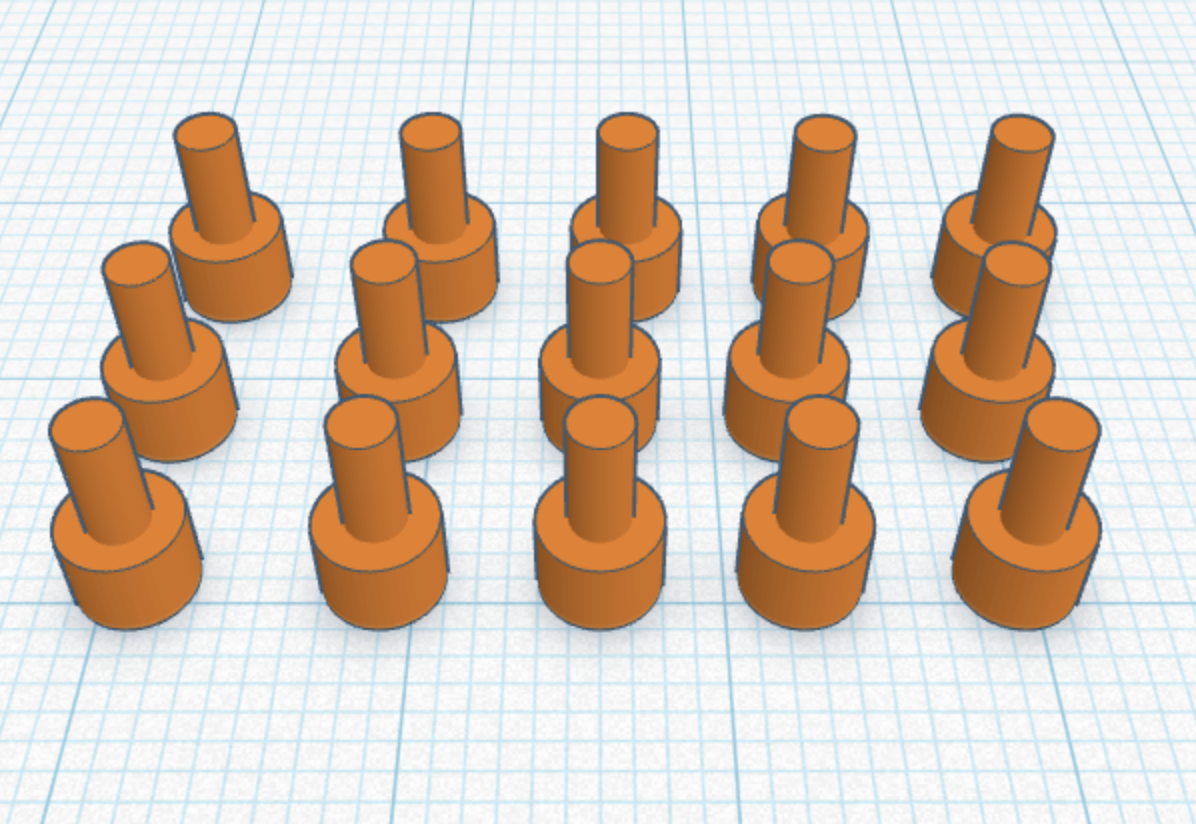

The nitty-gritty part of this actual blog post. Bear with me. In groups, people will be given a 3D-printed or woodcut of México, with holes already embedded into the country. These will be the data points (holes, literally just holes already made in the map) and pins, sized to fit them. The holes are rendered as a permanent facet of the map due to the nature of 3D printing, which makes me consider how the stories and narratives the map represents are always present, whether they are pinned and mapped or not. Which, by no means, should be uncomplicated, we should always consider why data gets mapped, what it is meant to demonstrate, what ends up entering, and what is left out and excluded.

Along with the country, they will also be given a mix of 14 notecards; on the front, each will have a year, the migrants’ nationality, and gender. In a longer workshop, I would leave parts of the data set unlabeled and have participants read the narrative on the other side and fill in the data themselves. Making data collection part of the activity and including a brief interrogation of what we synthesize and ultimately prioritize.

Slowly but surely, they will place a pin on the 3D map at the final location in Mexico mentioned in the narrative, where the hole already exists. By this point, the idea is that each pin they place on the map will serve as an act of accompaniment.

After they finish plotting all the index cards, the hope is that the participant will also be struck by the magnitude and scatter of a map filled with data points everywhere. It is here that the final questions address an essential part of GIS mapping: how does one filter through large datasets? How important were those labels at the front of the card to begin with? How do all the parts work together? Does this data filtering return us to a different directionality of accompaniment? These questions, along with this workshop, are truly a work in progress. While the process of prototyping countries and pins has taught me so many things (like patience and a love of failure), there is still so much I cannot yet estimate. And any comments or suggestions are always welcomed with gratitude.

Finally, I have a big rule about recognizing the role people play in helping me make a chaotic idea from my imagination feel and become tangible. None of this would have been possible without the Makerspace, Ammon, Shane, Brandon, and, lastly, David Coyoca, the man I bother with all my questions about teaching, and who helped me sort through the chaos that is my brainstorming. This final version-in-process would not have been possible without the team effort that praxis encourages. 10 out of 10. Thank you.

References Rodriguez, Ana Patricia. 2009. Dividing the Isthmus: Central American Transnational Histories, Literature, and Cultures. Austin: University of Texas Press

———— 2025 “The Art of (Un)Accompaniment: Salvadoran Child Refugee Narratives in the Twenty-first Century,” Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 49: Iss. 1, Article 8. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.2281