Hearing Silent Woolf

[This week I presented at the 2015 Huskey Research Exhibition at UVA. The talk was delivered from very schematic notes, but below is a rough recreation of what I discussed. The talk I gave is a crash course in a new project I’ve started working on with the generous help of the Scholars’ Lab that thinks about sound in Virginia Woolf’s career using computational methods. Eric Rochester, especially, has been endlessly giving of his time and expertise, helping me think through and prototype work on this material. The talk wound up receiving first prize for the digital humanities panel of which I was a part. The project is still very much inchoate, and I’d welcome thoughts on it.

When I talk to you, you make certain assumptions about me as a person based on what you’re hearing. You decide whether or not I might be worth paying attention to, and you develop a sense of our social relations based around the sound of my voice. The voice conveys and generates assumptions about the body and about power: am I making myself heard? Am I registering as a speaking voice? Am I worth listening to?

The human microphone, made famous by Occupy Wall Street, nicely encapsulates the social dimensions of sound that interest me: one person speaks, and the people around her repeat what she says more loudly, again and again, amplifying the human voice without technology. Sound literally moves through multiple bodies and structures the social relations between people, and the whole movement is an attempt to make a group of people heard by those who would rather not listen.

As a literary scholar, I am interested in how texts can speak in similar ways. The texts we read frequently contain large amounts of speech within them: conversations, monologues, poetic voice, etc. We talk about sound in texts all the time, and the same social and political dimensions of sound still remain even if a text appears silent on the page. If who can be heard and who gets to speak are both contested questions in the real world, they continue to structure our experiences of printed universes.

All of this brings me to the quotation mark. The humble piece of punctuation does a lot of work for us every day, and I want to think more closely about how it can help us understand how texts speak. The quotation mark is the most obvious point at which sound meets text. Computational methods tend to focus on the vocabulary of a text as the building blocks of meaning, but they can also help us turn quotation marks into objects of inquiry. Quotation marks can tell us a lot about how texts engage with the human voice, but there are lots of them in texts. Digital methods can help us make sense of the scale.

I examine Virginia Woolf’s quotation marks, in particular, for a number of reasons. Aesthetically, we can see her bridging the Victorian and modernist literary periods, though she tends to fall in with the latter of the two. Politically, she lived through periods of intense social and political upheaval at the beginning of the twentieth century. Very few recordings of Woolf remain, but she nonetheless thought deeply about sound recording. The worldwide market for gramophones exploded during her lifetime, and her texts frequently featured technologies of sound reproduction. Woolf’s gramophones frequently malfunction in her novels, and I’m interested in seeing how her quotation marks might analogously be irregular or broken intentionally. Woolf is especially good for thinking about punctuation marks in this way: she owned a printing press, and she often set type herself.

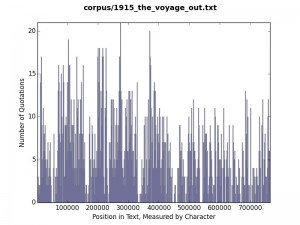

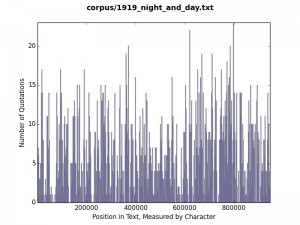

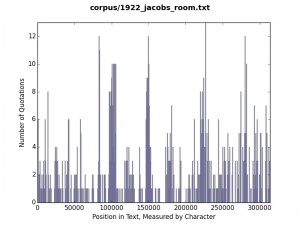

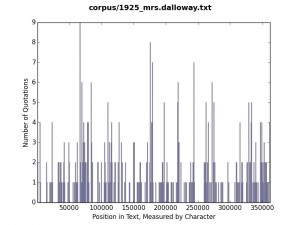

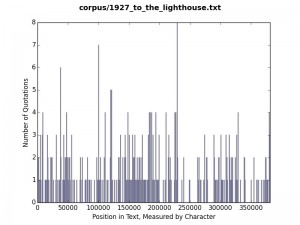

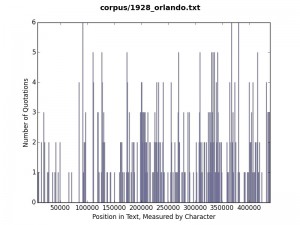

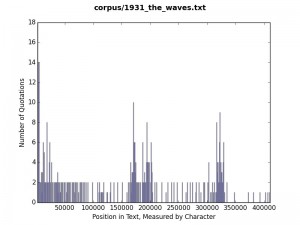

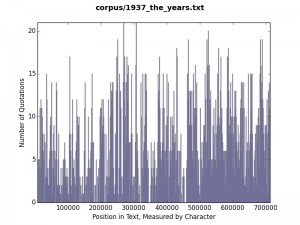

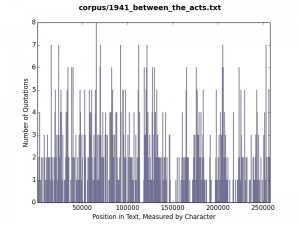

The following series of histograms gives a rough estimation of how Woolf’s use of quotation changes over the course of her career. On GitHub you can find the script I’ve been working on with Eric to generate these results. The number of quotations is plotted on the y-axis against their position in the novel on the x-axis, so each histogram represents more quoted speech with higher bars and more concentrated darknesses. If you have an especially good understanding of a particular novel, Mrs. Dalloway, say, you could pick out moments of intense conversation based on sudden spikes in the number of quotations. The histograms are organized in such a way that to read chronologically through Woolf’s career you would read left to right line by line, as you would the text of a book. The top-left histogram is Woolf’s earliest novel, the bottom-right corner her last.

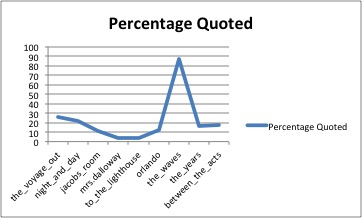

To my eye, the output suggests high concentrations of conversation in the novels at the beginning and ending of Woolf’s career. We can see that her middle period, especially, appears to have a significant decrease in the amount of quoted speech. In one sense, this might make sense to someone familiar with Woolf’s career. Her first two novels feel more typically Victorian in their aesthetics, and she really gets into the thick of modernist experiment with her third novel. One way we often describe the shift from Victorian to the modernist period is as a shift inward, away from society and towards the psychology of the self. So it makes sense that we might see the amount of conversation between multiple speaking bodies significantly fall away over the course of those novels. The seventh histogram is especially interesting, because it suggests the least amount of speech of anything in her corpus. But if we visualize things a different way, we see that this novel, The Waves, actually shows a huge spike in punctuated speech. This graph represents the percentage of each text that is contained within quotation marks, the amount of text represented as punctuated speech.

This might look like a problem with the data: how could the text with the fewest number of quotations also have the highest percentage of quoted speech? But the script is actually giving me exactly what I asked for: The Waves is a series of monologues by six disembodied voices, and the amount of non-speech text is extremely small. More generally, charting the percentage of quoted speech in the corpus appears to support my general readings of the original nine histograms: roughly three times as much punctuated speech in the early novels as in the middle period, with a slight leveling off in the end of her career.

We could think of The Waves as an anomaly, but I think it more clearly calls for a revision of such a reading of speech in Woolf’s career. The spike in quoted speech is a hint that there is something else going on in Woolf’s work. Perhaps we can use the example of The Waves to propose that there might be a range of discourses, of types of speech in Woolf’s corpus. Before I suggested that speech diminished in the middle of Woolf’s career, but that’s not exactly true. My suspicion is that it just enters a different mode. Consider these two passages, both quoted from Mrs. Dalloway:

Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself.

Times without number Clarissa had visited Evelyn Whitbread in a nursing home. Was Evelyn ill again? Evelyn was a good deal out of sorts, said Hugh, intimating by a kind of pout or swell of his very well-covered, manly, extremely handsome, perfectly upholstered body (he was almost too well dressed always, but presumably had to be, with his little job at Court) that his wife had some internal ailment, nothing serious, which, as an old friend, Clarissa Dalloway would quite understand without requiring him to specify.

In each case, the text implies speech by Mrs. Dalloway and by Hugh without marking it as such with punctuation marks. Discourse becomes submerged in the texture of the narrative, but it doesn’t disappear entirely. Moments like these suggest a range of discourses in Woolf’s corpus: dialogue, monologue, conversation, punctuated, implied, etc. All of these speech types have different implications, but it’s difficult to get a handle on them because of their scale. I began the project by simply trying to mark down moments of implied speech in Mrs. Dalloway by hand. Once I got to about two hundred, it seemed like it was time to ask the computer for help.

The current plan moving forward is to build a corpus of test passages containing both quoted speech and implied speech, train a python script against this set of passages, and then use this same script to search for instances of implied speech throughout Woolf’s corpus. Theoretically, at least, the script will search for a series of words that flag text as implied speech to a human reader - said, recalled, exclaimed, etc. Using this lexicon as a basis, the script would then pull out the context surrounding these words to produce a database of sentences meant to serve as speech. At Eric’s suggestion, I’m currently exploring the Natural Language Toolkit to take a stab at all of this. My own hypothesis is that there will be an inverse relationship between quoted speech and implied speech in her corpus, that the amount of speech left unflagged by quotation marks will increase in the middle of Woolf’s career. Once I have all this material, I’ll be able to subject the results to further analysis and to think more deeply about speech in Woolf’s work. Who speaks? What about? What counts as a voice, and what is left in an ambiguous, unsounded state?

The project is very much in its beginning stages, but it’s already opening up the way that I think about speech in Woolf’s text. It tries to untangle the relationship between our print record and our sonic record, and further work will help show how discourse is unfolding over time in the modernist period.