Humanities Unbound: Careers & Scholarship Beyond the Tenure Track

I’ve had the privilege of talking about graduate education reform and career preparation for humanities scholars at several universities this spring, including Stanford, NYU, and the University of Delaware. I’ve adapted the following from those presentations. The full dataset from the study that I discuss will be available later this summer, along with a more formal report.

Already familiar with the background of this project? Jump straight to the survey results.

Graduate students in the humanities thinking about their future careers face a fundamental incongruity: though humanities scholars thrive in a wide range of positions, many graduate programs operate as though every PhD student will become a tenured professor. While the disconnect between the number of tenure-track jobs available and the single-minded focus with which graduate programs prepare students for that specific career is not at all new, the problem is becoming ever more urgent due to the increasing casualization of academic labor, as well as the high levels of debt that many students bear once they complete their degrees.

Before I say anything more, though, I’d like to dispel a couple of associations that the title of my talk might call to mind.

First, I don’t intend to compare the humanities as a discipline to Prometheus, though at times the angst of the job market may make it feel like an apt image.

I also don’t mean to imply that the humanities are unraveling, though there is a useful connection to be made with that language. You may recall a recent article in the Chronicle of Higher Education by Michael Bérubé, past president of the Modern Language Association, which was called “Humanities Unraveled.” In the article, Bérubé refers to the humanities as “a seamless garment of crisis”—noting that every element, from the dissertation, to scholarly publishing, to time-to-degree, to labor issues, are so deeply interrelated and in such advanced states of disrepair that it feels impossible to pull on one thread without the entire system coming apart. Bérubé’s article does an excellent job of showing the ways in which these elements fit together, and why it’s imperative that we not lose sight of the system as a whole and the many points of intersection as we work to find solutions.

As important as that is, it isn’t quite what I want the focus of this talk to be.

Instead, the connection I want to make is something a bit more positive. I think that the discipline of the humanities should be disentangled—or, unbound—from the rigid academic pathway leading to the single goal of the tenure track job.

Instead of imagining graduate school as a pipeline, keeping everyone contained and moving in one direction to a pre-determined endpoint, what if we thought more about a sprinkler, with water exploding out in all directions?

It’s a rather simplistic metaphor, but I do think it’s a helpful image, especially since its outward spray is reminiscent of something that is not only practical, but that also brings joy.

Rather than focusing academic work inwardly, exclusively within academic institutions, humanities programs should be preparing students for much more flexibility in terms of audience and engagement. Even traditional scholarship has a growing potential to reach a wider and less specialized audience as scholarly publishing increasingly moves to open-access venues. But that’s only the tip of the iceberg. Scholars are publicly working through ideas on blogs and on Twitter, reaching a range of people from personal contacts, scholars, and grad students to interested strangers. Digital humanities projects are often public-facing and open to specialists and amateurs alike. And of course, people working in environments like museums, libraries, and presses have tangible public impact. Some humanities disciplines, such as history, do have a strong tradition in public engagement; public history is a well-developed sub-discipline, and many scholars work in museums, government, archives, and so on. But even there, the public branch has often been considered distinct from—and, unfortunately, less prestigious than—the research-focused side of the discipline.

The humanities must get more serious about its role relative to the public for a number of reasons. First, if we believe that our work can be a social good, with broad relevance to our cultures and societies, then we should be attentive to the public value of that work for reasons intrinsic to the work itself. Second, as public funding for the humanities becomes increasingly scarce, we must make a case for continued and strengthened support. If our work is not even visible, let alone relevant, to more than an academic audience, then we will have a weak case indeed. Third, it has long been the case that a large proportion of graduates engage in careers outside the professoriate, and yet those roles have typically been undervalued. We owe it to current and future graduate students to equip them for a broader range of roles, and to attribute to those roles the merit that they deserve. Embracing a broad spectrum of career options—in and around universities, as well as cultural heritage organizations, non-profits, government, and the private sector—won’t fix everything, but it would represent a significant step in the right direction.

Graduate programs can help prepare their students for a much broader professional world than simply the professoriate, but lacking data or strong models, it can be extremely difficult for individual programs to know what kinds of changes would be effective, and also to make a case for those changes. That’s why the Scholarly Communication Institute embarked on its recent study of perceptions of career preparation among humanities scholars: to determine a baseline from which to make specific recommendations for curricular changes.

In the absence of data that we thought was a crucial foundation for reform, SCI decided to survey what has come to be known as the “alt-ac” community. But first we had to think about how to answer a common question: what does alt-ac even mean?

The term was coined—more or less accidentally—in a 2009 Twitter conversation between Bethany Nowviskie (of UVa and SCI) and Jason Rhody (at the National Endowment for the Humanities). Short for “alternative academic,” the term became useful shorthand to refer to jobs in and around the academy, but outside the professoriate. At the time, jobs tended to be classified as either “academic” or “non-academic,” with everything outside the professoriate being relegated to the “non” category. But many scholars—including Nowviskie and Rhody—were (and are) doing innovative, productive, thought-provoking work in all kinds of positions. “Alt-ac” was a way to capture the kind of intellectually-stimulating roles that at that time were being brushed aside as viable scholarly career paths. Nowviskie went on to create #Alt-Academy, an online volume of essays treating a range of topics related to the pursuit and development of these various careers.

Because the term is not at all formal, it means different things to different people. While the concept is something that people are eager to talk about, and while the term itself has both expanded in meaning and proven useful beyond what was initially imagined, there’s also a certain degree of discomfort with the phrase. Some find that it perpetuates an unfortunate (and false) binary of career options or reinforces the primacy of tenure-track employment—which, of course, is exactly what it was meant to alleviate. Others simply don’t find that the term resonates for them, considering it too narrow, or redundant with existing categories. Still others have expressed concern that #alt-ac is being held up as an unrealistic panacea for the perpetually abysmal academic job market, yet without necessarily creating new jobs.

All of these are valid critiques, and really, I would love it if the term became unncessary and we could simply speak of career choices without the looming dominance of the tenure track. Until that day comes, I tend to take a broad view of what “alt-ac” can signify, and I’ll continue to use it here as shorthand for a wide variety of career paths. I’m actually quite comfortable with the unsettled nature of the term, as I think that it helps us to continue having useful and important conversations. I highlight the disagreement just to say that because of the differing understandings of the term, before we could even begin to study the various constellations of alternative academic careers, we needed a better idea of who felt that the terminology resonated with the kind of work they were doing.

To get a sense of what others mean by “alt-ac”, we took the exploratory step of creating a public database where people could voluntarily add their names to a loose, public community of other alt-ac practitioners. We built the database within the framework of the #Alt-Academy project in order to leverage the energy of existing conversations, then stepped back to see what the results would be. We quickly had over two hundred and fifty entries from individuals in many different positions. Browsing the database is a great starting point for grad students or others who want to see the kinds of work that humanists are doing in the world. It’s still open to new entries, so feel free to check it out and add your own name if you think of your work along these lines.

Once we created the database, we moved on to the second, more formal phase of the study, which included two confidential surveys. The primary survey targeted people with advanced humanities degrees who self-identify as working in alternative academic careers—precisely the people who identified themselves in the database, and we so we used the database as an initial source of potential respondents. The secondary survey targeted employers that oversee people with advanced humanities degrees. By questioning both, we were able to gain a more well-rounded perspective that balances some of the challenges inherent in self-reported answers.

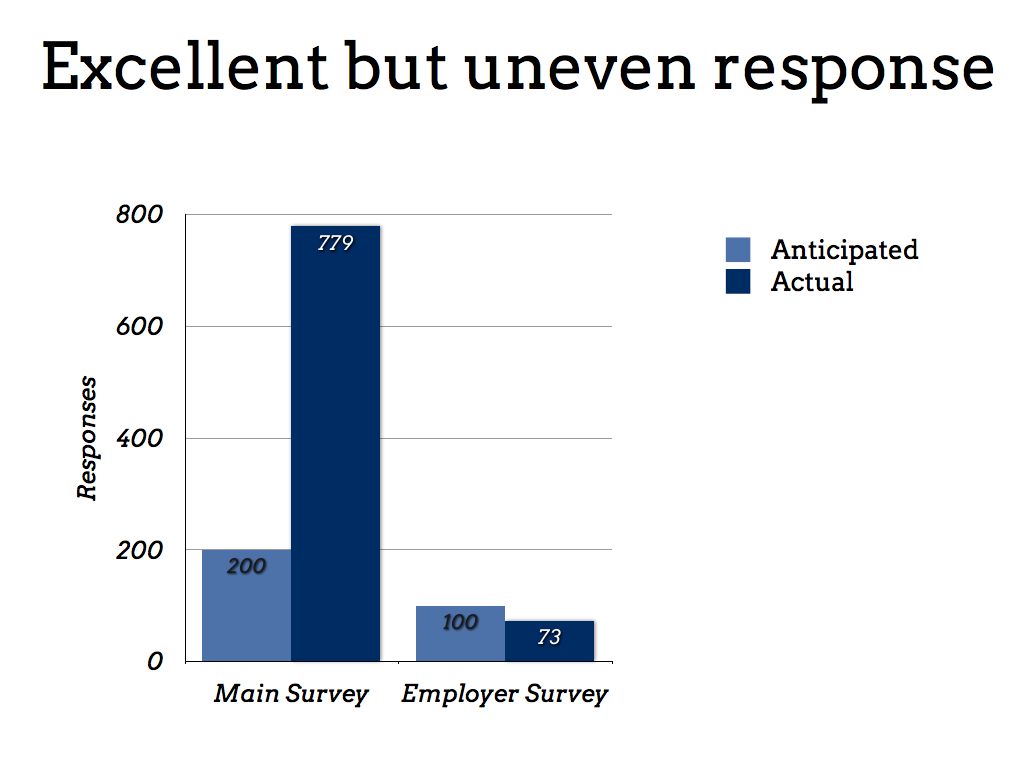

A couple of things about the response rate highlighted important discrepancies. We set an initial goal of 200 responses on the main survey, and 100 on the employer survey. Responses to the main survey totaled nearly 800 when we closed it, for almost four times our goal.

Interestingly, this is a much higher number than the public database saw, despite the fact that, first, the survey required a more significant investment of time, and second, it was open for responses during a much shorter window than the database, which is still open now. I suspect that this is in part due to a lingering discomfort with publicly stating that one has pursued a path outside the professoriate; in fact, when the database launched, a number of people contacted me to say that while they supported the project, they didn’t want advisors or others from their institution to know the kind of work they were doing. I find this incredibly distressing.

The employer survey, on the other hand, attracted far fewer responses, totaling around 75. This is a significant finding in itself, as it shows a pronounced disconnect between the motivations of job seekers compared to employers in thinking through the issues at hand. The questions of career paths and graduate education reform are understandably much more urgent for those that have gone through the process and made any number of difficult decisions.

Now, to turn to the data.

Much of the data from the surveys will be unsurprising to people who have already been thinking about these questions. As we might anticipate, people report entering graduate school expecting to become professors; they receive very little advice or training for any other career; and yet many different circumstances lead them into other paths. But even if the broad contours of the results are unsurprising, the specific data is useful to ground the general anecdotal impressions that many of us have long shared. Indeed, one of the primary goals of the survey is to help move the conversation from anecdote to data.

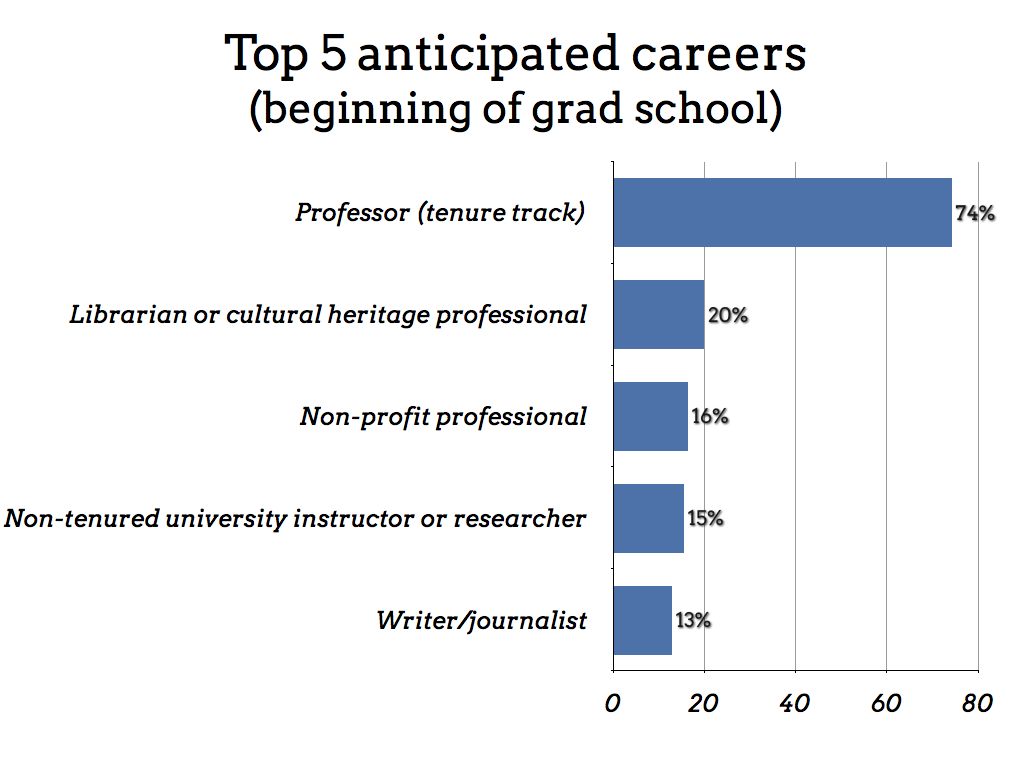

For instance, asked to identify the career or careers they expected to pursue when they started graduate school, 74% indicated that they expected to obtain positions as tenure-track professors. As you can see, that response far outpaces any others, even though respondents could select multiple options. (As an aside, that’s also why the results here and on many subsequent slides add up to more than 100%. Because so many alt-ac positions are hybrid, we didn’t want to limit people to one option in their responses.)

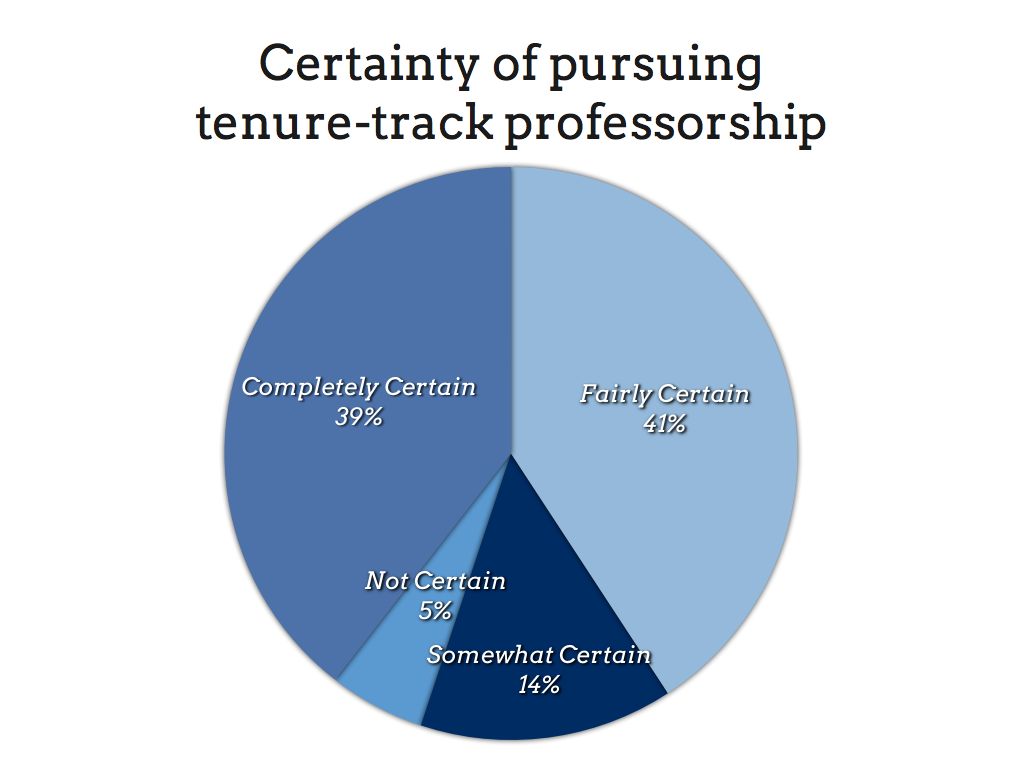

What is perhaps more interesting is their level of confidence: of that 74%, 80% report feeling fairly certain or completely certain that professorship was the career they would pursue.

Keep in mind that because we targeted alt-ac practitioners, none of the survey respondents are tenured or tenure-track professors; they are all working in other domains. So even among the body of people who are working in other roles, the clear expectation at the outset of graduate school was for a future career as a professor.

These expectations are not at all aligned with the realities of the academic job market, and they haven’t been for some time. The labor equation for university teaching has continued to shift dramatically in recent years, with non-tenure-track and part-time labor constituting a majority of instructional roles. The 2011 report on the Survey of Earned Doctorates reported another alarming statistic: 43% of humanities PhD recipients have no job or postdoctoral commitment on graduation—and that’s for any commitment, including temporary or contingent positions. Many graduate students begin their studies without a clear picture of their future employment prospects. What this signals to me is that we are failing at bringing informed students into the graduate education system.

But whose responsibility is it to provide information about career prospects? It seems clear to me that it’s something that must be addressed before graduate education begins, and then reiterated in the admissions process and throughout the program, ideally by a trusted advisor. To be honest, I see this as an ethical issue: it is deeply problematic to admit students to a program if their expectations for the program’s outcome are not accurate. This is even more true if students are admitted to unfunded positions and must incur debt as they earn their degrees.

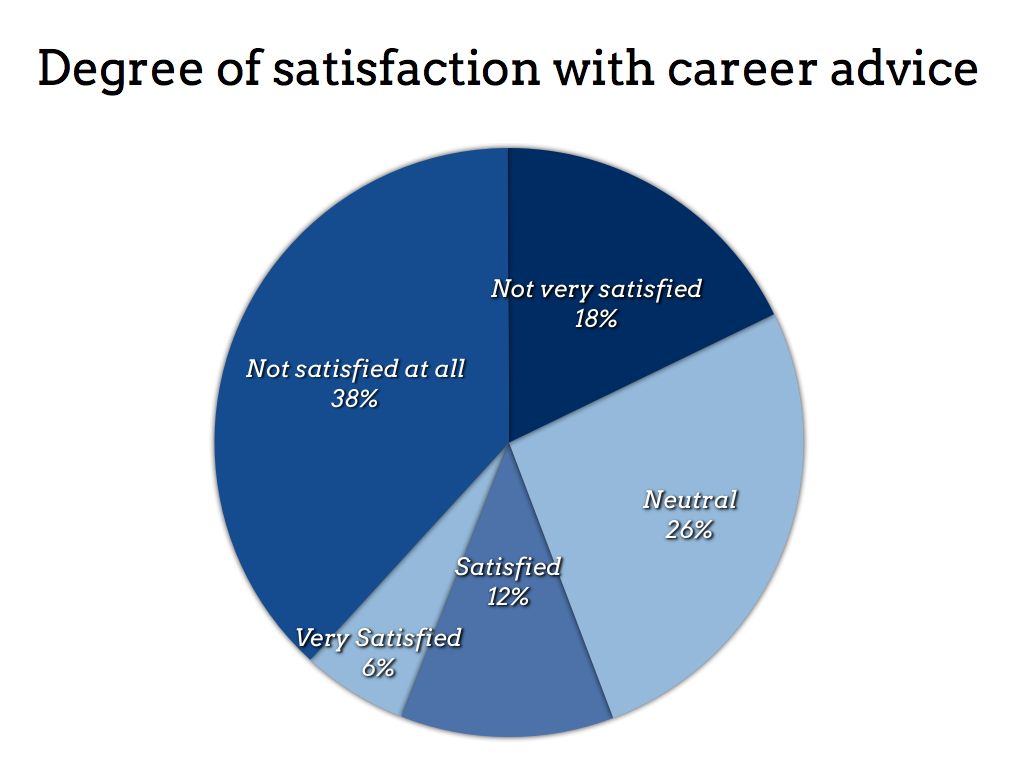

Deepening the problem, students report receiving little or no preparation for careers outside the professoriate, even though we’re at a moment when the need for information about a variety of careers is most acute. Only 18% reported feeling satisfied or very satisfied with the preparation they received for alternative academic careers.

The responses are rooted in perception, so there may be resources available that students are not taking advantage of—but whatever the reason, they do not feel that they are being adequately prepared. Again, this probably comes as no surprise, but it does reveal that we have significant room for improvement.

Many programs have access to two rich resources that they leave untapped: their own staff, and their own graduates.

An easy first step for universities to take would be to list all of their non-professorial staff members that hold PhDs. Stanford has done something like this, compiling information about people in the Stanford system (including the Press and Libraries) that are willing to serve as mentors for humanities graduate students. Stanford has also developed a speaker series that highlights scholars working in hybrid and non-faculty roles on campus.

Tracking graduates is a little more complicated, but no less important. There may be confidentiality issues involved, but there are surely ways that positions could be reported in aggregate and supplemented with a few individual examples. The more significant hurdle is that because prestige continues to be linked to tenure-track placement rate, many programs either do not track the careers of anyone outside this category, or if they do, they do not publish the information they have for fear (I suspect) of tarnishing their reputation relative to other schools.

But the vibrant alt-ac movement suggests that the time is ripe to measure prestige in other ways. I would think that programs would be eager to publicize the often high-level alt-ac careers of their graduates, and that such information could be a strong draw for prospective students. I’ve long wondered why graduate programs find it so difficult to track their former students, when development offices seem to be the very first to know the whereabouts of alumni. New research by a third-party consultancy, the Lilli Research Group, has shown that it’s possible to determine the professional outcomes of graduates with a surprising degree of accuracy, even using only public records, but I think that this work should be taken on internally. Programs simply must do a better job of knowing what kinds of work their graduates are doing.

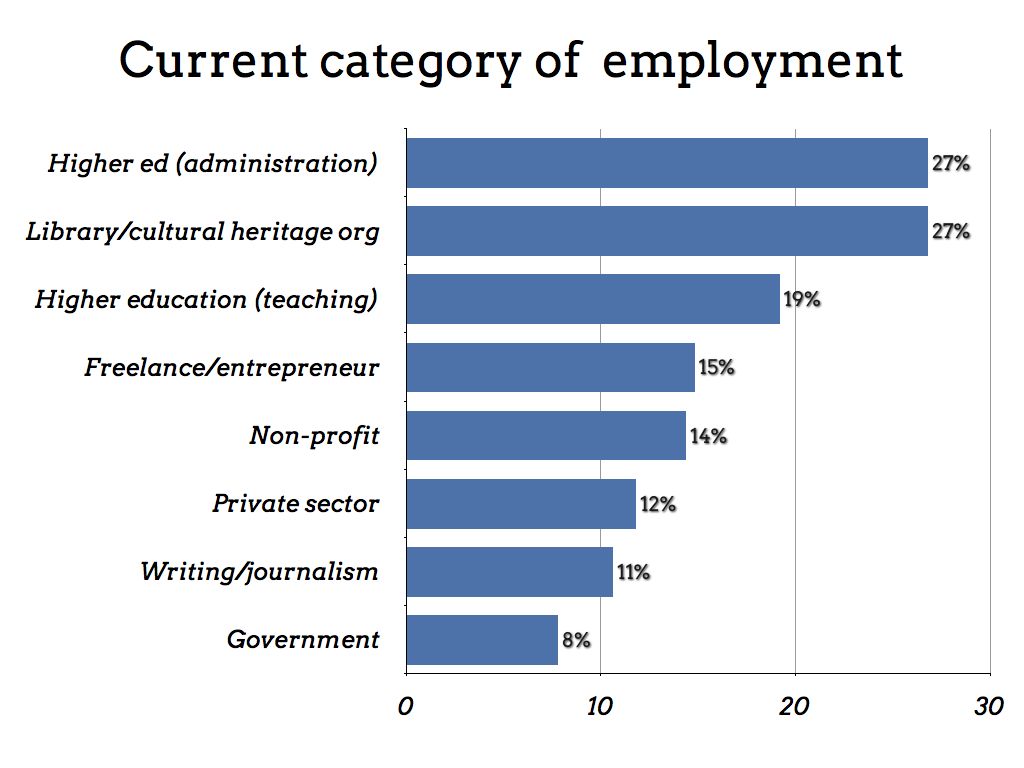

So, where are people working after graduate school? As you can see, instead of the professoriate, the respondents reported working in a number of different types of workplaces. A large majority of respondents categorized their positions as being within universities, libraries, and other cultural heritage organizations.

Parenthetically, this is one area where the definition of alt-ac gets fuzzy; some people prefer to think of alternative academic careers as only those that are within the university. I’ve mentioned that I take a broader view. Personally, I think it’s useful to consider not so much a specific job or career, but rather an approach: a way of seeing one’s work through the lens of academic training, and of incorporating scholarly methods into the way that work is done. It means engaging in work with the same intellectual curiosity that fueled the desire to go to graduate school in the first place, and applying the same kinds of skills—be they close reading, historical inquiry, written argumentation, or whatever else—to the tasks at hand. Thinking this way encourages us to seek out the unexpected places where people are finding their intellectual curiosity piqued and their research skills tested and sharpened.

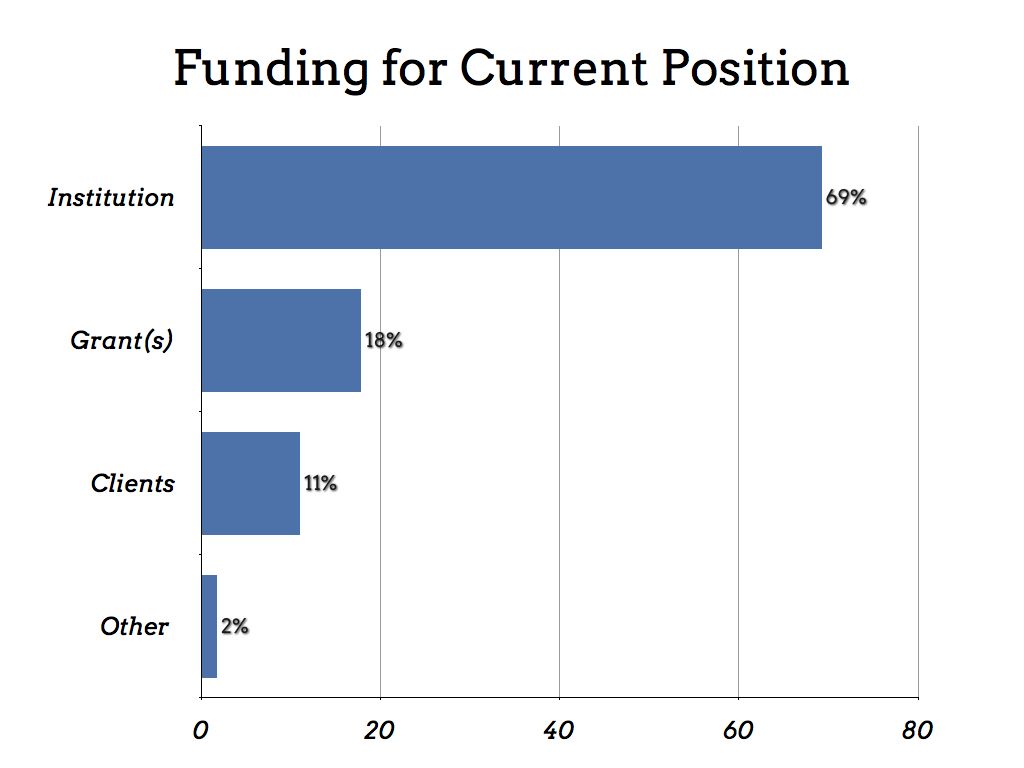

The next slide might actually be a bit of a pleasant surprise. Despite a concern that encouraging graduate students to pursue more varied lines of employment pushes them into short-term positions with unstable funding, in fact relatively few respondents report this as their situation. Only 18% are in positions currently funded wholly or partially by grants, and, while this chart doesn’t show it, just 5% are in positions with a specified end date.

That is not to say that alternative academic positions are a quick fix; after all, we’re not talking about creating new jobs where none existed, but rather about recognizing existing opportunities. I especially want to reiterate that issues surrounding the academic labor market are pervasive and serious, particularly as universities rely on contingent labor to an ever-greater degree. But there are good, solid opportunities available that should figure into the ways that we train and advise graduate students. And the public will benefit from the perspective and expertise of humanities scholars whose voice extends beyond the classroom or academic journal.

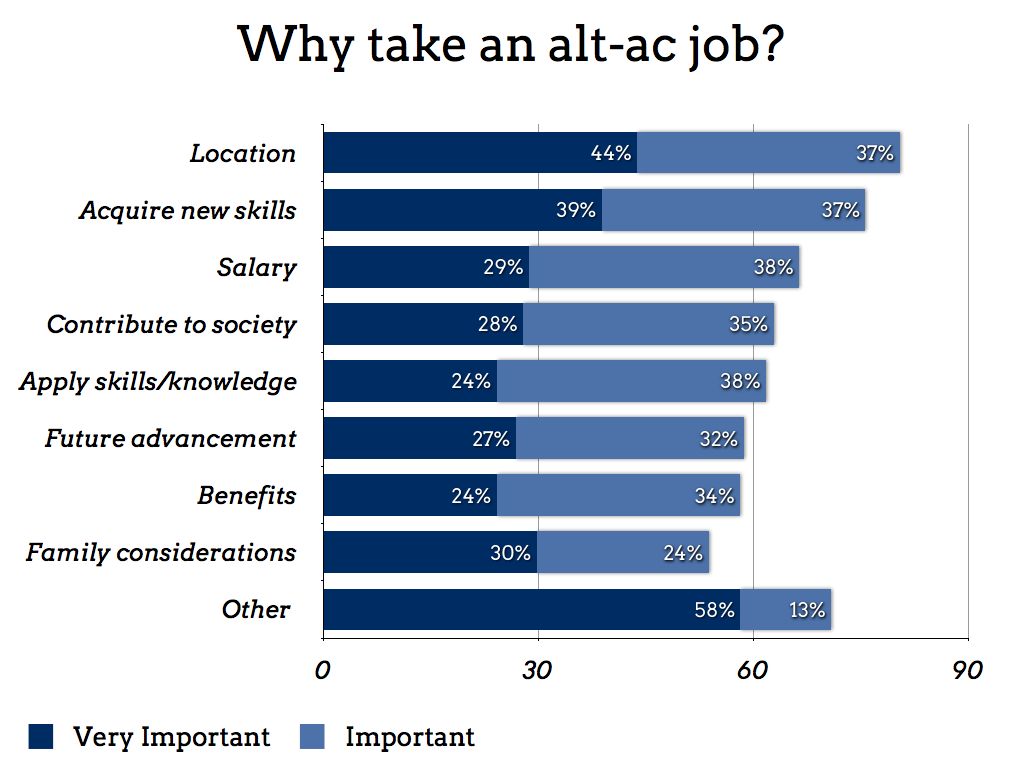

The reasons that people pursue careers beyond the tenure track are varied and complex. Location tops the list, which makes sense as a contrast to the near total lack of geographic choice afforded by academic job searches.

Beyond that, people report pursuing alt-ac jobs for reasons ranging from the practical and immediate—salary, benefits, family considerations—to more future- and goal-oriented reasons, such as the desire to gain new skills, contribute to society, and advance in one’s career. Many people filled in their own responses as well, with the most common trends in the open text field being a desire for greater freedom, dissatisfaction with what a faculty career would look like, and much more simply, the need to find a job. A note of urgency and, sometimes, desperation came through in a number of these responses.

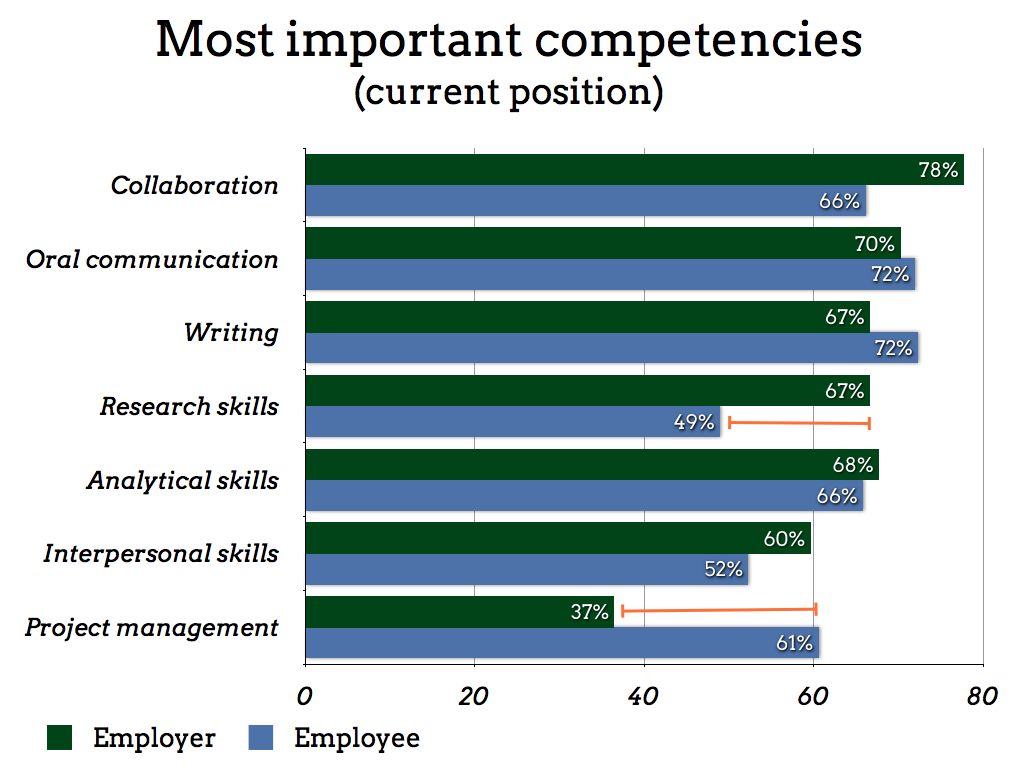

Keeping in mind that the employer sample was quite small compared to the main sample (and therefore less reliable), I’d like to look at some of the competencies that both groups considered important to the alt-ac positions that they hold or supervise. Some of the skills are core elements of graduate work, such as writing, research skills, and analytical skills. Both groups value many of the skills at similar levels; however, there are a couple of discrepancies.

I find it particularly interesting that alt-ac employees undervalued their research skills relative to employers. I suspect that there are two reasons for this: first, there may be some activities that employees do not recognize as research because it leads to a different end result (such as a decision being made, rather than a journal article being published). Second, it may be a skill that has become so natural that former grad students fail to recognize it as something that sets them apart in their jobs.

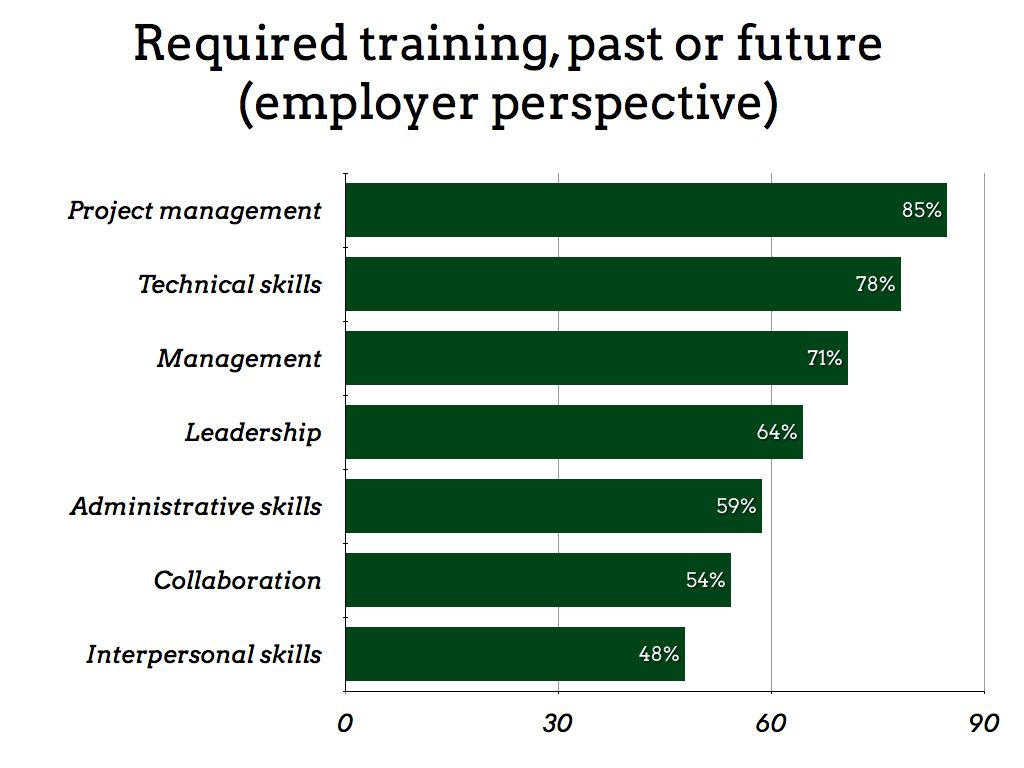

On the other hand, alt-ac employees tended to overvalue the importance of project management among the competencies that their jobs required. That said, project management actually tops the list of areas where alt-ac employees needed training, according to employers:

To me, this suggests that employees overvalued the skill because they found it to be a challenging skill that they needed to learn on the job, and so it took on an outsized importance in their minds.

Employers also cited technical and managerial skills as areas that needed training. While the importance of those two skills would certainly depend on the type of position, others, such as collaboration, are useful in almost any work environment. Even simple things, like adapting to office culture, can also prove to be surprisingly challenging if graduates have not had much work experience outside of universities.

The good news is that all of the elements that make stronger employees would also be hugely beneficial for those grads that do go on to become professors. While students are generally well prepared for research and teaching, they aren’t necessarily ready for the service aspect of a professorship, which incorporates many of the same skills that other employers seek. Many of the skills can also contribute to more creative teaching and research. By rethinking their curricula in such a way that students gain experience in things like collaborative project development and public engagement, departments would be strengthening their students’ future prospects regardless of the paths they choose to take.

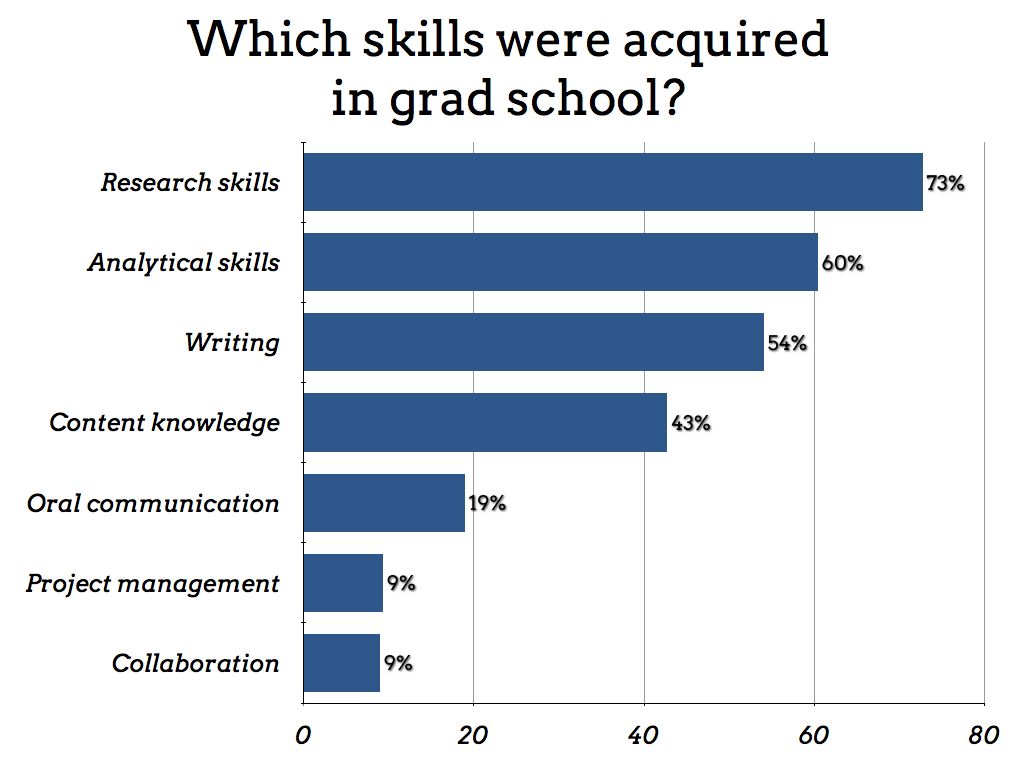

It’s not surprising that employers find that alt-ac employees need training in skills like project management and collaboration. Employees themselves also recognize that these are by and large not skills that they acquire in graduate school. Even among those who felt that their skills in these areas were strong, they noted that they gained them outside of their graduate program—for instance, through jobs or internships.

Of course, the core skills of graduate training—especially research, writing, and analytical skills—are highly valued by employers. These skills are the reasons that employers will often hire PhDs even if the degree is not strictly required by the position. It’s important that students don’t undervalue (or insufficiently articulate) the ways that graduate study already equips them for broader roles, particularly in the methods and generalized skills that are critical to the process.

One thing seems clear: the persistent myth that there’s nothing but a single academic job market available to graduates is damaging, and extricating graduate education from the expectation of tenure-track employment has the potential to benefit students, institutions, and the health of the humanities more broadly. However, as long as norms are reinforced within departments—by faculty and students both—it will be difficult for any change to be effective.

Again, low tenure-track employment rates are not a new problem, but as the survey responses show, departments by and large are not succeeding at providing accurate and realistic information to their students, and many graduates still feel stigmatized when they pursue different types of careers.

For change to be possible, it’s essential that institutional norms and measures of prestige shift in favor of highlighting successful outcomes across a broader spectrum of possibilities. And it’s important that graduate programs begin exploring ways that they can better prepare their students while maintaining the integrity of humanistic scholarship.

Admittedly, that can seem an incredibly difficult barrier to cross without successful examples to emulate. Having good models can not only ease the technical challenges of establishing a new program—like building support, establishing a program’s structure, and so on—but can also alleviate the potential social challenges of striking out on a new path.

To that end, SCI has just launched another project that we hope will be a useful complement to the survey data: the Praxis Network.

The Praxis Network is a new showcase of a small handful of truly excellent programs that are already up and running. Each of these programs can be thought of as one possible response to the question of how to equip emerging scholars for a range of career outcomes without sacrificing the core values or methodologies of the humanities, and without increasing time-to-degree.

Institutions that wish to explore making changes can really benefit from seeing existing models, but currently, finding information about, and comparing, some of these new programs can be quite challenging. There are a lot of reasons for this: for instance, they may be housed in different parts of their institutions—such as departments, traditional or digital humanities centers, or libraries. They are often, but not always, small and nimble. Most of all, they are all quite different, though there are trends and commonalities among them. We wanted to create a space that made it easy for people to see what makes these great programs tick, and we wanted to present the information in a way that makes sense for anyone, whether they are administrators, faculty, students, or the general public.

The site doesn’t aim to be a comprehensive database of all praxis-type programs; instead, it’s meant to be a small cross-section of programs that are different enough from one another that together they give an impression of the landscape.

The anchor of the network is UVa’s Praxis Program, which brings together interdisciplinary cohorts of six doctoral students to collectively build a single tool that will be useful for humanities research or pedagogy. In the course of the year-long fellowship, they learn technical skills and project management under the mentorship of the Scholars’ Lab research and development team. But they also learn innumerable “soft” skills as they navigate the creation of a group charter, determine their priorities, think through their disciplinary values and assumptions, blog about the process, and publicly launch the tool.

Along with UVa’s Praxis Program, which Bethany Nowviskie directs, we selected a few differently-inflected programs to highlight. Most are graduate programs. These include:

* the Cultural Heritage Informatics Initiative, led by Ethan Watrall at Michigan State University;

-

CUNY Graduate Center’s Digital Fellows, under Matt Gold;

-

the joint MA/MSc program in Digital Humanities at University College London, led by Simon Mahony;

-

and the new PhD Lab in Digital Knowledge at Duke University, run by Cathy Davidson and David Bell.

We’re also working with two undergraduate programs:

-

the Mellon Scholars program at Hope College, which William Pannapacker leads;

-

and Brock University’s Interactive Arts and Science Program, under Kevin Kee.

For the moment, the website is the main product, and sharing information is the main goal. We hope that the ideas found on the site prove to be both useful and inspiring. There’s a wealth of exceptional work represented here, and we hope that it’s presented in a way that makes it easy for people to understand and compare various aspects of each program.

The mission of each program might be the category that has the greatest degree of similarity across institutions. The goals of each are student-focused, digitally-inflected, interdisciplinary, and frequently oriented around collaborative projects.

One common tenet is learning in public and exposing the process, warts and all. Many of the students grapple with the notion that our learning happens in unexpected ways—including through failure—and come to a greater degree of comfort with exposing their own uncertainties. Because humanities students are socialized to show their work only once it’s polished, this can be a very uncomfortable experience, but it’s one that leads to particularly fruitful results.

All of the programs encourage some kind of public engagement, whether through blogs, public-facing projects, or more traditional venues like conference presentations. Some of the programs include partnerships with local cultural heritage sites, tech companies, or other potential employers, which allows students to immediately see potential applications for the work they’re doing.

We then look at structure, which shows a lot more variety. Some of the programs are fellowships that offer a stipend, while others require tuition; they may be as short as five weeks, or as long as three years. They may be credit-bearing or extracurricular, with requirements that are formal or loose.

One thing worth noting here is that most of the programs are fairly small and competitive. This has some real advantages: students benefit from strong mentorship and close collaborations with one another in small cohorts. When other institutions move toward making praxis-like changes, they often take the form of these kinds of small, competitive programs. This is a great start, but I’d also love to see more movement toward broad-based change that touches entire departments. To make that happen, we would have to see strong advocacy for curricular change and the acceptance of new modes of scholarship for credit and degrees. This kind of change is happening, but it’s happening very slowly.

For digital and other non-traditional work to be recognized as scholarship, universities need examples of existing work to point to. Importantly, the site highlights the research products that the students are generating through the course of the programs. They often look quite different from the typical seminar paper, and demonstrate not only rigorous scholarly work, but also a creativity and vibrancy not often found in standard papers.

Highlighting this kind of work is aligned with the efforts of organizations like the Modern Language Association, which establishes guidelines and offers workshops on the evaluation of digital work for tenure and promotion.

The site then focuses on the people that are the core of each program. Every single program is characterized by strong, dedicated leaders and curious, intelligent students, and is invariably colored by the interactions among them. This can be both an asset and a challenge, as programs that rest on the shoulders of just a few individuals need to think about questions of continuity. But creating something new requires risk-taking, which is often easier for an individual or small group than for an entire department.

Resources may feel like one of the most significant barriers to implementing programs of this nature, so we’ve detailed the support structure of each. Money is a crucial aspect of this: some programs are grant-funded, of course, while others have hard budget lines within their institutions. Physical space and personnel are also key resources, and play an important role in the scope of the program.

A program’s future goals depend on a combination of many of the factors above. In some cases, the programs hope to grow, either within their institution or by forming cross-institutional partnerships. In other cases, however, the program’s success depends on its smallness, so some do not wish to expand, but rather intend to focus on how to continue innovating while staying light-weight.

And finally, the nuts and bolts of the programs. If you’re thinking of developing something like what you see on the site, the information in this section will help you to know some key questions, potential risks, and other things to keep in mind as you consider how to proceed.

I think of each program in the Praxis Network as an instantiation of the kinds of innovative solutions that can alleviate the issues that the survey uncovered. Humanities programs have the opportunity to better serve their students as well as the public by really examining what our core values are, and rethinking the methods we use to teach them. The Praxis Network programs show just a few possible ways to move toward collaborative projects, public engagement, and embracing an ethos of openness and exploration.

Praxis Network members will be meeting during the coming months to discuss what kinds of cross-institutional collaborations might be most effective. At the same time, SCI will convene meetings in conjunction with CHCI (the Consortium of Humanities Centers and Institutes) and centerNet, its digital counterpart, to further explore points of intervention and to develop potential pilot programs that could leverage the particular strengths of traditional and digital humanities centers.

So, those programs are great examples to follow, but you might be wondering what you can do right now, especially if you’re a graduate student.

First, if you’re not getting the information you need from your program, seek it out. If nothing else, start with the resources that are available on my website.

Second, connect with people. Browse #Alt-Academy and the database that I mentioned earlier. Find people that are doing interesting work and see if they’d be willing to talk with you about how they got there—many of us are, especially since our own paths were so often not what we expected them to be! Encourage your department to help set up mentorships with alumni from the department, or with scholar-practitioners working in the university. Engage in online networks that are relevant to your interests. Find a mentor that can support you.

Third, think about the skills and experience that you already have, how you might frame it for different kinds of jobs, and what else you might need to be a competitive applicant for positions that interest you. Depending on your circumstances, you might carefully consider whether to take an external job for a year of your graduate program rather than work as a TA if you have limited job experience outside of teaching.

Finally, there are lightweight training opportunities that you can pursue even if your home department is quite traditional. The Digital Humanities Summer and Winter Institutes are great examples of short programs that enable students (or faculty, staff, or anyone else) to pick up new skills while also building a strong network.

Beyond what I’ve talked about here, so much more is possible within and across existing programs. SCI hopes that our current work will help begin to rise the tide of transparency and innovation more broadly.

Source:

Source: