Hybrid Literature: Ruth Ozeki’s A Tale for the Time Being

As a scholar of contemporary literature, I have naturally been drawn to the incredible literary innovation that has exploded in the wake of digital developments. I’m certainly not alone in my interest, and critics such as Katherine Hayles, Marie-Laure Ryan, Wolfgang Hallet, and Jan-Noël Thon have discussed the role of new media in literary studies, including video games, hypertext fiction, and comic books. Yet here I want to focus on contemporary writers who have begun exploiting new technologies in even more subtle ways, using technology as a means of supplementing more traditional printed books. More specifically, these texts employ a “both-and” approach, relying upon traditional publishing platforms (no matter how international the dissemination) while including new media elements that extend beyond print to reach the burgeoning generation of digital readers. Such works range from Indra Sinha’s online stories and sketches that extend the fictional world of his Animal’s People to Ali Smith’s incorporation of images and “Google poems” in Artful and David Mitchell’s creation of a live Twitter account for one of his characters in Slade House. Even as these hybrid texts experiment with new technologies and print platforms, so do they use new technology for the purposes of publishing and branding, in order to reach a different audience, and as a means of developing a new, innovative aesthetic. So let’s look more closely at one of these hybrid texts in particular, namely, Ruth Ozeki’s 2013 novel, A Tale for the Time Being.

So here’s the back-story: Ozeki’s A Tale for the Time Being pivots between the fictional worlds of Naoko Yasutani (“Nao,” pronounced “Now”) and a fictional persona known as Ruth Ozeki, who is modeled upon Ozeki herself. The story takes place on a small Canadian island, where Ruth discovers the diary of a sixteen year-old Japanese girl preserved within a Hello Kitty lunchbox. Ruth, who is herself part Japanese and able to translate the diarist’s – Nao’s – scrawl, subsequently begins reading Nao’s diary, and A Tale for the Time Being alternates between recording Ruth’s English translation (complete with footnotes) of Nao’s diary and Ruth’s own life struggles as she engages with Nao’s text.

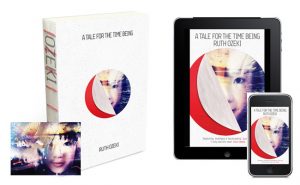

Published simultaneously not only in hardback and paperback editions, but also as an e-book and an audio download, Ozeki’s novel stands as a pioneering work in terms of experimental publication. That is, Canongate (the publisher of the first published edition of A Tale in the UK) was particularly attentive to creating a brand for Ozeki’s novel that reached across print and digital audiences. As such, the covers of all these editions feature the face of a girl superimposed on a landscape, which is partially concealed behind a peeled-back red circle (reminiscent of the Japanese flag) – see Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Screen grab from the Canongate website

Cate Cannon, the head of marketing at Canongate, has remarked on this focus during the publication planning of Ozeki’s novel. She says: “The animation and design translates across our digital outdoor advertising, our website and all our editions, creating a brand identity for this novel that is enriching, engaging and progressive” (Montgomery). Nonetheless, the real innovative aspect of Canongate’s publishing lies not in the similarities between each edition, but rather in the subtle differences, for each of the covers of these versions differed slightly based on medium. The hardback version, for instance, was published with the complete image of the girl’s face printed on the cover; this image was wholly concealed by a red sticker that the reader could physically peel back. This format was unique to the hardback version, and the paperback edition simply printed the image as pictured above, with the red circle partially concealing the girl’s face. Yet the paperback also employed technology in a unique way to create a kind of hybrid cover: this has resulted in the first “interactive book cover.” Book designer Zoë Sadokierski explains: “Published by Canongate, art director Rafi Romaya collaborated with creative agency Big Active. ….The ‘interactive’ aspect of the physical book cover involves Blippar technology (augmented reality) – using the camera on a smart phone/tablet, you can link to audio/visual material, via the Blippar app” (Sadokierski). In other words, if you have a paperback copy and have downloaded the Blippar app, you can point your smartphone or tablet at the cover: a virtual sticker will appear on your device, which you can “peel back” to reveal the girl’s face; this face has even been animated to move for 15 seconds (you can view the Blippar “interactive cover” here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N7vpb7UPK6E).

This attention to technology and branding is further manifested in Ozeki’s creation of a supplementary “book trailer,” in which Ruth (played by Ozeki) discovers Nao’s diary (see Ozeki’s website, OzekiLand: http://www.ruthozeki.com/). Even as it blends media by applying a form previously reserved for television shows and movies to a novel, this book trailer appeals to Ozeki’s tech-savvy audience of e-readers, and indeed, the e-book links to YouTube videos, including interviews with Ozeki and video reviews of the novel. While these various covers and animations may sound gimmicky, we can nonetheless see how media and technology have become increasingly important both for authorial branding and in order to reach a larger, more tech-savvy audience.

As I’ve examined Ozeki’s supplementary use of technology in her otherwise fairly traditional print novel, I’ve been struck by several questions: How does the use of augmented reality – both through applications such as Blippar and videos of fictional works in which the author and main character appear as the same individual – alter our understanding of the reality-fictional divide? Do digital spaces provide a kind of “hyper reality,” and if so, how might we interpret this hyper-reality? In what other ways are “hybrid” literary works experimenting with technology, and what implications does such experimentation have upon the development of literature? In short, I’m excited to see how contemporary writers continue to engage with digital developments!

Works Cited

Montgomery, Angus. “An Interactive Book Cover From Canongate and Big Active.” Design Week. N.p., 22 Feb. 2013. Web. 30 Aug. 2016.

Ozeki, Ruth. A Tale for the Time Being. New York: Penguin Books, 2013. Print.

Sadokierski, Zoe. “On Publication Design: Interactive Book Covers.” zoesadokierski.blogspot.com. N.p., 23 Feb. 2013. Web. 30 Aug. 2016.