Introductions: Meet Charm and Wit, or Wit and Charm

Sarah E. Berkowitz

I will be working with James Ascher this summer on a Scholar’s Lab Digital Humanities Project Incubator Fellowship. Our project consists of creating a digital edition of “Characters” from Samuel Butler’s posthumous (1759). James and I are both rising fifth year Ph.D. candidates in the English Department, and we both study the eighteenth century, but there the similarities end. I study primarily novels, and I’m primarily interested in post-structuralist literary criticism. My dissertation focuses on male characters in the late eighteenth-century novel, and I’m wildly interested in Butler’s text because of what I think it can tell us about characters outside of novels in the eighteenth century. Oh, and did I mention? I have absolutely no digital humanities experience. Suffice it to say James’s interests and experiences are very different from mine, but I’ll let him introduce himself.

Because we have an Incubator fellowship, our goal is to create a fast and furious prototype by the end of the summer. My job is primarily to provide a critical framework for thinking about character. In the dream version of this project, I would be writing the footnotes that explain and contextualize Butler’s individual characters. But, I still need to learn some basic computer skills and, and because of the truncated time frame I have to learn them fast! I’ve start using a free website to teach myself basic command line, and have started to go through the built-in Emacs tutorial. Next on the list is learning Git. The hope is that I can master enough basic skills by Memorial Day that I can meaningfully contribute to our conversations about design. This seems like a tall order right now, but I’m working on it a little every day. Then the real fun will begin.

James P. Ascher

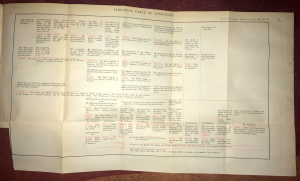

Sarah Berkowitz has kindly provided a gracious introduction to our project and our collaboration, but I’d be remiss if I didn’t write of my reciprocal enthusiasm. Characteristic of our collaboration, we debated if we were in fact different in our interest in literary criticism—we feel different, but are we? As we talk, the names we engage with are different: David Brewer, Deidre Lynch, and Catherine Gallagher provide mortar the bricks of Sarah’s thinking and G. T. Tanselle, David Foxon, and James Raven are smeared like honey on goblet of medicine that I try to present the world. Of course, I think that I’m critiquing literature—as the eighteenth century would have defined it: written language presented to the public in printed form. Of course, Sarah is right that the burden of understanding how those marks on paper came to be is so large that I seldom get a chance to talk about phenomena like character;–it’s too far to induce from printing history to ideology. Hence, my excitement in this project. I feel as though we’re reaching across a gap, trying to find a bridge between the physical facts of items and the theoretical preoccupations of post-structuralist literary criticism. I think of William Whewell’s inductive tables as a sort of emblem for us !

Whewell proposes the table as a way of visualizing the method behind the slow progress of induction building on the ideas of the past—two separate explanations become one and then that one is combined with another explanation to make an even grander theory. Repeat forever, as first causes—the ultimate end of such a chain of induction, are unreachable. In this way, he imagines enacting Francis Bacon’s great instauration: renewing the accumulation of private natural-history knowledge as theories that explain the world. You collect data, find patterns, write a theory, and make a theory out of those theories. I think this accurately describes what both of us are doing, but on different parts of the chart that would represent literature. Sarah builds on the long history of the study of character; I build on the history of printed forms of meaning. What this project can helpfully show us is the bracket that would correspond to the induced theory that contains both of these chains of induction. Surely, we wouldn’t bother reading printed works if it weren’t for characters? Surely, we couldn’t read about as many characters if it weren’t for printed works? Okay, that means they relate, but how?