Ivanhoe considerations for the next cohort

Welcome to the next Praxis cohort! As Purdom mentioned yesterday in her post, the 2014-2015 Praxis Fellows will continue working on the Ivanhoe Game. As last year’s Praxis project manager, I frequently found myself in the position of spokesperson for Ivanhoe. People would ask me, “What is Ivanhoe?” and I would deliver an answer like “Ivanhoe is a platform for making collaborative interventions in a text via role play.” While a pretty good description of the game, this response nonetheless invites many questions—questions which my dazzled but bewildered auditors would inevitably ask:

“How do you play?”

“Can you win?”

“What do you mean by a ‘role’?”

“What do you mean by ‘intervention’?”

“Do you have to have read Ivanhoe to play?”

Well, the last question is straightforward enough (you do not have to have read the novel of that name by Sir Walter Scott to play), but the others are a bit more complex. Ivanhoe originators Johanna Drucker and Jerome McGann and SpecLab pioneers Bethany Nowviskie, Geoffrey Rockwell, and Chad Sansing debated these very questions in a special issue of TextTechnology (12:2) in 2003, when Ivanhoe development was in full swing. Eleven years later, our Praxis cohort took up these questions while building Ivanhoe as a WordPress Theme. We designed our Ivanhoe to be as open-ended and non-prescriptive as possible, not wanting to predetermine game play in any way. But what would be wrong with exploring the possibilities of Ivanhoe, showing users what we found, and inviting users to join that conversation? Perhaps Praxers’ own experimentation and transparency regarding their experiences might better guide users toward getting into Ivanhoe and trying it out themselves.

I’m excited to see where the next cohort takes Ivanhoe, how they interpret it, and what kinds of games they play. But at this crucial moment before the games begin, I feel it necessary to impart a few thoughts on what our own cohort considered to be the essential elements of Ivanhoe. I will begin by listing them:

-

The Text

-

Moves

-

Role Play

-

Collaboration

The Text

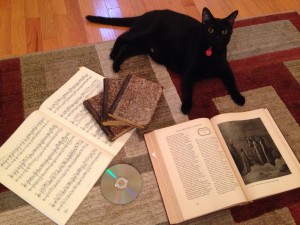

Any Ivanhoe game begins with a text. But what constitutes a ‘text’? On the original Ivanhoe informational website, the SpecLab researchers termed it a “‘discourse field,’ the documentary manifestation of a set of ideas that people want to investigate collaboratively.” Our cohort considered an Ivanhoe text to be merely the focus of the interpretation. This could be a literary text, a work of visual art, a piece of music, a film, or even a concept—such as a historical time period. One example of the last would be the Suffragette Journalism Game, which took as its ‘text’ the 19th-century women’s suffrage protests in England. To some extent, the Ivanhoe game we played on the Elgin Marbles was also a concept game, since we didn’t have the marbles themselves on hand to study and interpret but rather found ourselves interpreting the whole historical legacy of the marbles. So a ‘concept text’ can work well for Ivanhoe, but is a concept–which may come without “documentary manifestation”–a legitimate text? Are there any constraints on what can be a ‘concept text’? Is there a point in an Ivanhoe game at which a concept, loosely interpreted, can break down and the game drift into meaninglessness? Do you need a sense of textual integrity for the game to have coherence and meaning?

The Move

The second integral feature of an Ivanhoe game is the move, which our developer Scott Bailey succinctly defined as a “self-conscious act of interpretation.” These acts constitute what we like to refer to as “textual interventions.” The first Ivanhoe games played by Drucker and McGann, as well as the SpecLab researchers, involved actual changes made directly into the texts: Players added text, changed it, or deleted it from works such as Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe and Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw. Our cohort began with a game on Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Tell-tale Heart,” which, following its predecessors, involved changes to the text itself. As we found ourselves becoming more and more interdisciplinary in our aims, however, the typical move became more a commentary on the text than changes to it. Does mere interpretation actually intervene in a text? Which term is more characteristic of an Ivanhoe move? What are we actually doing when we make an Ivanhoe move, and how do moves make the game itself progress?

Role Play

[Actors refused to participate]

Role play has always been the cornerstone of the Ivanhoe Game: each player assumes a role—a particular voice or critical stance from which to make moves. In the SpecLab’s A Turn of the Screw game, players even chose aliases so that other players couldn’t guess their roles; arguably, these aliases add another level of role play. But when we interpret a text, don’t we automatically assume a role of some sort? When I read, I approach a text from the role of “Stephanie reading for fun” or “Stephanie reading to have brilliant ideas,” for instance—and my reading styles in these roles, alas, are very different. Thus, it is important to keep in mind the self-conscious in the definition of a role. These are “self-conscious acts of interpretation”: your role must be deliberate and specific, and you must constantly be reconsidering your role and striving to make moves which develop that role. It is a more directed manner of analysis than simply trying to come up with points of interest for class discussion, as the Stephanie-bent-on-brilliance attempts to do. The element of self consciousness, therefore, is absolutely integral to the Ivanhoe Game.

Directly related to self consciousness, what about the idea of the role journal? The SpecLab Turn of the Screw game included role journals in which players commented on why they made certain moves; these journals were kept secret from other players. Additionally, players also could comment on other players’ moves; these comments were public. This game had two ways players could be self-conscious of game play. I particularly want to pose this question to the next cohort: is the role journal a core feature of Ivanhoe? Our own cohort spent hours debating this question (see Scott’s excellent post on the issue), but after we decided to keep the role journal, it quickly was pushed to the back-burner during development and became a secondary feature in terms of importance. Must an Ivanhoe game have an actual role journal, or is the role journal merely an emblem of the self-conscious attitude of the players? Is its function simply to keep players adhering to their roles, or does it serve other purposes? This is a question which I would love to see this year’s cohort test.

Collaboration

Lastly, Ivanhoe must have players; for me, this means it is collaborative. Even if players are competing, the result is still collaboration because one player’s ideas necessarily inform and impact those of the other players. This collaboration is one feature which we considered to be very important to Ivanhoe; it’s what makes it a game—or as Francesca wrote in her post last year, gamification, an idea and debate worth consideration for the next cohort but one which I will not attempt to discuss here. Can you have a one-person Ivanhoe game? I do not think so, but then that is really an opinion guided by my firm belief in the final–and perhaps most essential–Ivanhoe feature: FUN! Grab some friends and have fun with collaborative criticism in an Ivanhoe game of your own!

Conclusion…?

What I realize as I go down the list of core features is 1) what I assumed were core features are perhaps not so self evident as I had thought, and 2) in attempting to create a list I have hovered dangerously—and somewhat tantalizingly—close to deconstructing Ivanhoe altogether. Why? What is so elusive about Ivanhoe? My neat-and-tidy list ended up melting into a series of questions and the important but nonetheless vague mantra of “fun.”

Perhaps, then, my contribution to the next cohort is not a list of Ivanhoe essentials, but a few questions which they can consider as they start their play-testing. I will be fascinated to watch their progress on the Praxis blog, and I encourage readers to follow it as well. Watch for their reflections on Ivanhoe, and even join in the discussion by leaving comments. Play an Ivanhoe game, and let us know what you think are the core features. Ivanhoe, after all, is about getting conversation started. Good luck, Praxers, and let’s get gaming!