Outside the Pipeline: From Anecdote to Data

_I gave the following presentation at SCI’s recent meeting on rethinking graduate education. It was the first time I’ve publicly discussed results from the study on career preparation in humanities graduate programs that I’ve written about previously. I was honored to discuss the topic with our extremely knowledgeable group of participants, and the thoughtful questions and comments that the talk generated will inform my thinking as I work toward a more formal report and analysis. I would welcome additional comments and questions. A PDF of the presentation is also available.

I’m thrilled to have the opportunity to present some of the early findings from the Scholarly Communication Institute’s recent study on perceptions of career preparation in humanities graduate programs.

The impetus for this study came from recommendations made at SCI’s ninth summer meeting in 2011, where rethinking graduate education emerged as one of the critical priorities for the current humanities landscape. The study complements the series of meetings SCI is hosting this year and next, of which this meeting is the first. The primary goal of the study is to move from anecdote to data in the conversation about alternative academic careers and career preparation, in hopes of providing a body of data that can help support programs wishing to modify their graduate curricula. We finished collecting data at the beginning of October, so the analysis is not complete, but already raises some provocative questions.

We were very pleased with the number of responses that we received. At the same time, the response rate also highlighted an important discrepancy.

The study included two surveys. The primary survey targeted people with advanced humanities degrees who self-identify as working in alternative academic careers. (A somewhat loose definition, to be sure – I’ll discuss our methodology in a moment.) A second, shorter survey targeted employers that oversee one or more employees with advanced humanities degrees.

We set an initial goal of 200 responses on the main survey, and 100 on the employer survey. We were blown away by the responses to the main survey, which totaled nearly 800 when we closed it, for almost four times our goal. The employer survey, however, attracted far fewer responses, totaling around 80. This is a significant finding in itself, as it shows a pronounced disconnect between the motivations of job seekers compared to employers. Any recommendations SCI makes must keep this discrepancy in mind.

I’d like to jump straight into some of our findings, many of which will not come as a surprise – but again, the goal was to get numbers to back up the general sense that many of us have about these questions.

First, a large majority of students enter graduate school expecting to pursue careers as professors – a total of 74%. What is perhaps more interesting is their level of confidence: of that 74%, 80% report feeling fairly certain or completely certain that this was the career they would pursue. These expectations are not at all aligned with the current realities of the academic job market.

What this signals to me is that we are failing at bringing informed students into the system. This raises a few questions:

–First, whose responsibility is it to help incoming students understand their postgraduate options? This is a bit outside of the scope of this particular meeting, but it becomes our concern when students enter without the knowledge that they need. –Second, what is the role of faculty and advisors relative to uninformed students? –Third, and more speculative, should post-graduate planning play into admissions in any way? Is there an ethical responsibility here, especially considered in conjunction with increasing student debt? Put differently, should departments be admitting students – particularly if funding is limited or unavailable – if they do not understand their post-graduate options?

Deepening the problem, students report receiving little or no preparation for careers outside the professoriate, even though we’re at a moment when the need for information about a variety of careers is most acute.

Only 18% reported feeling satisfied or very satisfied with the preparation they received for alternative academic careers. The responses are rooted in perception, so there may be resources available that students are not taking advantage of – but whatever the reason, the bottom line is that students do not feel that they are being adequately prepared. Again, this probably comes as no surprise, but we have significant room for improvement.

This raises additional questions:

–Are faculty adequately prepared to provide the kinds of advice that students need? –Should they be? –If it’s not the faculty’s role, then whose role is it? Perhaps alumni or third-party service providers could fill the gap; if so, what are the trade-offs of outsourcing these kinds of preparatory roles to organizations or individuals outside of departments?

Along with questions that asked people to choose from pre-selected options, we also included a number of open-ended questions. The survey tapped into what can be an intensely emotional topic, and the wide range of responses we received suggests that people felt comfortable being candid.

The variety of emotions expressed in open-ended responses varied from optimistic and happy, to bitter and resentful. Many people report feeling betrayed.

Below is another sampling of the kinds of responses we received in the open-ended questions. We’ll be doing more systematic analysis of these responses in the weeks ahead, but for the time being, this will give you an idea of the kinds of reactions and reflections that our respondents provided.

We received a wide range of practical suggestions, too, such as offering more one-off workshops; including short credit or non-credit courses; and connecting students with alumni working in varied positions. It’s worth noting that while many were skeptical about even the possibility of creating a meaningful cultural change, they emphasized that for sustainable change to occur at all, it is important that it comes from within existing structures if it is to be perceived as valid.

One thing seems clear: the persistent myth that there is nothing but a single academic job market available to graduates is damaging, and extricating graduate education from the expectation of tenure-track employment has the potential to benefit students, institutions, and the health of the humanities more broadly. However, as long as norms are reinforced within departments – by faculty and students both – it will be difficult for any change to be effective.

Low tenure-track employment rates are not a new problem, but as the responses on the previous slides show, departments are not succeeding at providing accurate and realistic information to their students.

Perceived reputational risk is a significant roadblock to increased transparency regarding post-graduate career paths. A common refrain among the respondents was a call to collect and publicize employment data. However, departments have little incentive to collect this information, and even less motivation to make it public, especially if they think it makes them appear unfavorable relative to peer departments.

Are departments the only groups who can collect this kind of information? If they are, how can we change the incentives such that departments find it advantageous to publicize all types of employment among their graduates?

Turning now to the employer survey: while we haven’t yet done rigorous analysis on the qualitative responses, I did want to give a taste of the kinds of things employers indicate they would like to see.

First, some specific skills come up frequently, including project management, the ability to work with and manage people, collaboration, and written and verbal communication with a variety of audiences.

In addition, employers mention a number of broader aptitudes, like a commitment to public engagement, general work experience outside of academia, and an ability to adjust to the culture of different types of workplaces. Many employers placed high value on these employees’ understanding of academic structures and environments, but in order to serve as the valuable cultural translators that they could be, employees with graduate training also need to be sensitive to the ways in which academic environments differ from other workplace cultures. For those that graduate without limited (or no) outside work experience, the gap can be very challenging to bridge.

While I’ve only scratched the surface of the study’s findings, I’d like to shift gears in order to highlight what we hope will be the first of many concrete actions to come of this study: the development of the Praxis Network.

This is a network of several existing programs that are focusing on innovative models of methodological training, along the lines of the Praxis Program at the University of Virginia. We anticipate that many programs that want to make changes will want to look to existing models for guidance, and by highlighting a handful of differently-inflected programs, we can bring together some patterns and commonalities among them, while also underscoring the unique idiosyncrasies of each – the strong individuals providing leadership; the particularities of an institution; the available infrastructure; the funding model; and so on. In addition to sharing information with the public, we hope that the network will enable increased possibilities for communication and collaboration among the participants of each program.

In addition to the Praxis Program, we are currently working with Ethan Watrall at the Cultural Heritage Informatics Initiative; Matt Gold with the CUNY Digital Humanities Initiative; Claire Warwick and Melissa Terras at UCL’s Centre for Digital Humanities; and Bill Pannapacker with the Hope College Mellon Scholars program. The participating programs may fluctuate somewhat, but the intention is to keep the network small – more as a showcase than a comprehensive directory.

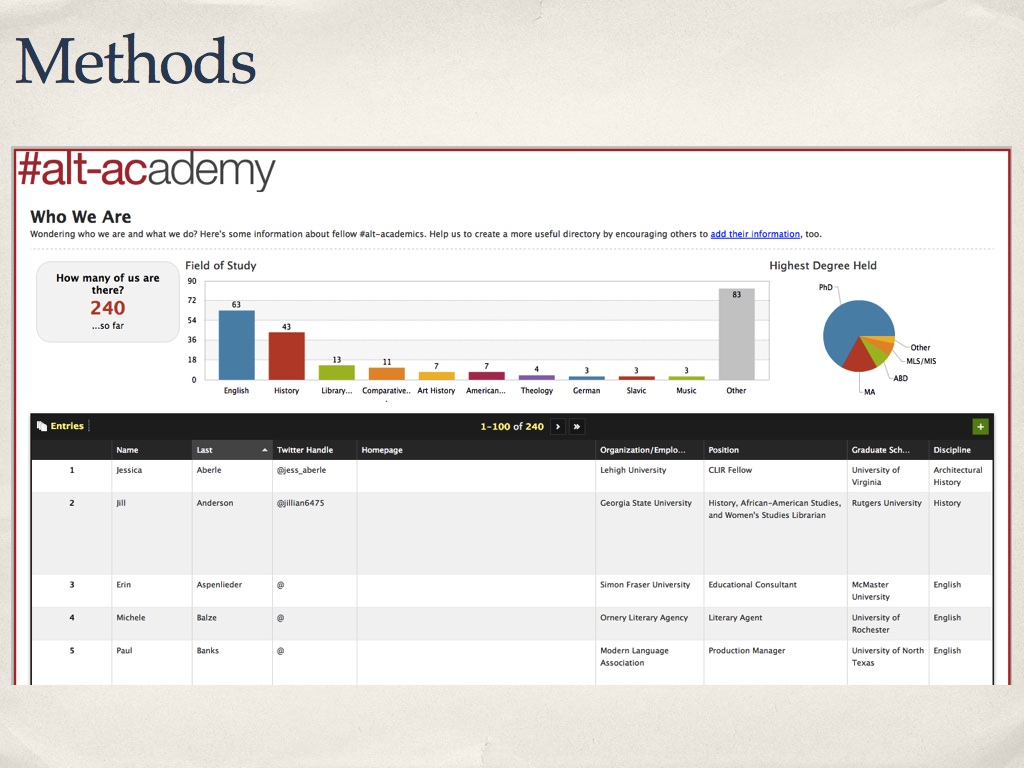

I’d like to circle back briefly to discuss our methods. First, the study had two main phases: so far, I’ve focused on the second, confidential phase. The first phase was public.

In order to scope out the terrain of individuals to include in the survey, the first phase involved creating a public database where people comfortable enough to publicly identify as “alt-ac” practitioners could add their names to form a loose community of peers.

We built the database within the framework of the #alt-academy project in order to leverage the energy of existing conversations. “Alt-ac” may not be a perfect moniker, but it has created a space to talk about careers that are not quite what most people envision as academic careers (within the professoriate), but that are not completely outside the academic sphere, either. Many people have found it to be an incredibly useful umbrella term, and have used it to talk about the kinds of intellectually stimulating careers that can be found outside the professoriate.

We were pleased with the initial turnout, and found that people were engaging more deeply than expected. It’s worth noting that even though the database has been open for a much longer period of time than the survey was (and it remains open to new entries now), far fewer people participated in the public space than in the confidential survey space. To me, this suggests that there is still a sense of discomfort – and even shame – about having pursued a job outside the traditional pipeline.

Once we launched the surveys themselves, we used this public group as an initial body of potential respondents. Because we were working with an unknown population, our subsequent distribution focused on “opt-in” strategies—social media, word of mouth, listervs, and traditional media coverage. While this method has definite weaknesses, we hoped to learn something not only from the content of the responses, but from the number and type of respondents.

One reason this study was important because even though the topic is deeply connected with other persistent issues in higher education, there were significant gaps in the data available from previous studies.

One of the most closely aligned studies was completed just recently by the Council on Graduate Schools and the Educational Testing Service. The study, Pathways Through Graduate Schools and Into Careers, examines current and former graduate students’ career expectations, their awareness of career opportunities, and the actual career paths they pursued. However, the study focused on a broad range of disciplines, which means that it could not go into much depth on concerns that are particular to the humanities. Further, the data is unpublished, so at least at this point, it is not possible to disaggregate the humanities respondents from the STEM respondents.

A 1996 study by Maresi Nerad and Joseph Cerny at the University of Washington, PhDs Ten Years Later, focused on similarly relevant questions. However, the only humanities discipline represented in their data was English. In addition, the study excluded people who left their programs before completing the degree, and because so many people exit their programs if they decide not to pursue an academic career, we wanted to include their perspectives. Of course, the data is now more than 15 years old, and the cohort graduated more than 25 years ago, making it overdue for an updated look.

Finally, we will build off of information collected by broad surveys like the Survey of Earned Doctorates, which provides useful baseline demographics but limited depth.

The data from the study does have some significant limitations:

We had limited data to use as a foundation or control, as I just mentioned; we were working with a population with fuzzy boundaries; and we relied on self-identification and self-reporting. For all of these reasons, the results should be considered more exploratory than definitive, and the respondents cannot be considered a representative sample. We see this survey as an important initial step, and we hope others will build on it.

We still have a good deal of work ahead of us, and because we want this survey to be maximally useful to our partners in humanities centers and digital humanities centers, as well as the broader humanities ecosystem, I’d welcome input in a number of areas. In the weeks and months ahead, we’ll be engaging in deeper analysis of the data; we’ll be conducting follow-up interviews by phone and email with a number of participants who indicated their willingness to do so; and we’ll be continuing the conversation in more depth at subsequent SCI meetings. We’ll eventually be making recommendations based on the data analysis. Finally, we’ll be publishing a final report in partnership with the Council on Library and Information Resources, and we’ll also publish the data so that others can work with it.

As the discussion on rethinking methodological training continues, I hope you’ll keep this study in mind and share your thoughts with me on how it can best serve its audiences. Thank you!

References Council of Graduate Schools. Pathways Through Graduate School and Into Careers. 2012. <http://pathwaysreport.org/>

“Doctorate Recipients from U.S. Universities: 2010.” Based on data from the Survey of Earned Doctorates. National Science Foundation, June 2012. <http://www.nsf.gov/statistics/sed/>

Nerad, Maresi, and Joseph Cerny. “PhDs: Ten Years Later.” Center for Innovation and Research in Graduate Education, University of Washington; 1996. <http://depts.washington.edu/cirgeweb/c/research/phd-career-path-surveys/phds-ten-years-later/>

Nerad, Maresi, and Joseph Cerny. “From Rumors to Facts: Career Outcomes of English PhDs.” ADE bulletin 32.7 (1999): 11. <http://www.mla.org/bulletin_124043>

Photo Credits Slide 1: “Pipeline” by stigwaage Slide 7: “Pencils” by Elle * Slide 11: “He Didn’t ‘Mind the Gap’” by Scott Smith Slide 12: “Fenced In Part 2” by gomattolson