Preserving, Reconstructing, & Teaching in 3D

The destruction of historic monuments has been a frequent topic in the news lately due to the Syrian and ISIS conflicts. The destruction of historic mosques and, most recently, the Temple of Baal in Palmyra have sent shockwaves through the international community. The public outcry for cultural casualties has been so overwhelming that it has prompted backlash and criticism questioning the value of such monuments when confronted with overwhelming human suffering and death. This is not the place to debate the value of historical monuments and I cannot speak for anyone other than myself, but I anticipate that the focus of horror expressed by many institutions and academics is not the rejection of human suffering, but rather an acknowledgement of our own limitations to make a difference. Art and architecture play a key role in political legitimization and cultural identity, especially during wartime when these factors can bolster or inhibit support. The ability to preserve the history and cultural heritage of this region through our scholarship expresses a hope for a time when such artifacts (and the history they represent) can be studied and valued openly again. The variety of digital tools and methodologies embraced by the digital humanities has offered a small, but powerful way to preserve what we still can. Project Mosul, for example, is using crowd-sourced photographs to reconstruct monuments digitally. Harvard and Oxford have also created their own “monuments men” to scan some of the most threatened monuments. Artist Morehshin Allahyari is also considering the relationship between preservation, destruction, and technology in her art as she reconstructs and 3D prints the artifacts lost to ISIS destruction.

This summer, my own research took me as far as possible from the war-torn Middle East to the quiet fields of Iceland. The Monasticism in Iceland archaeology project provided me with an opportunity to work directly with artifacts and grapple with the complicated considerations of heritage preservation for the first time. Iconoclasm is not an issue in Iceland as it is in the Middle East; rather, site isolation and exposure to Iceland’s volatile climate create difficulties for sharing and preserving Iceland’s material past. A beautifully carved twelfth-century stone from Hítardalur represents these concerns in a particularly striking way. Likely a remnant of a failed medieval monastery, this unique mustachioed face lies in the field where it was discovered, open to the elements. When first told about this unique carving, I assumed it would be safely locked in a museum, climate controlled and secured. I did not expect to find this rare stone in a field adjacent to a private farmhouse, exposed to weather, theft, and accidents. Over the years, this open exposure has weathered the details of the face and two additional sculptures of similar composition were lost. I have never worked with artifacts outside of a museum setting and it was difficult for me to grasp that there are scores of objects that museums cannot accommodate, that the removal of artifacts—even for their protection and accessibility—can be interpreted as illegitimate or even criminal overreach. In fact, it raises multiple questions about artifact and heritage ownership that I cannot even begin to answer. As the cases of the Parthenon/Elgin Marbles and Kennewick Man demonstrate, accessibility, preservation, and ownership do not always coincide.

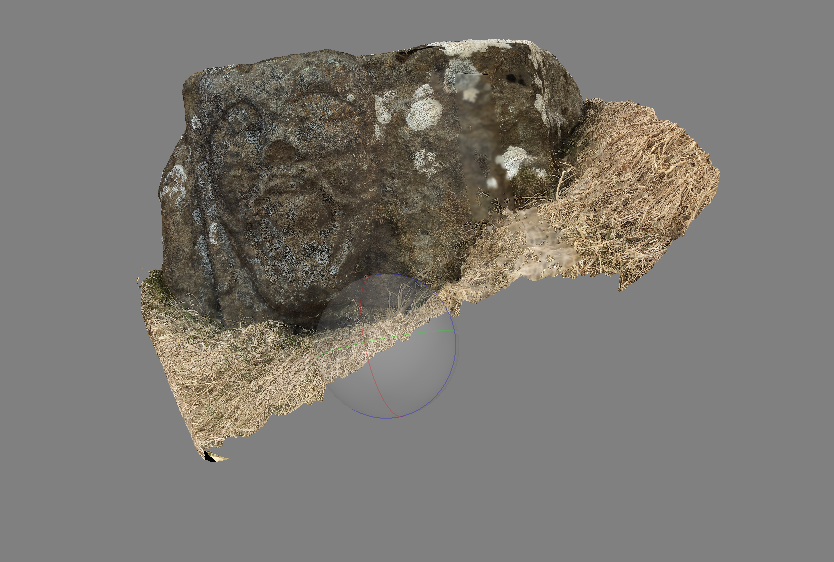

Hítardalur sculpture, photograph taken in June 2015. Note the deterioration of facial details.

I admit that I am still grappling with these issues, as my priorities of accessibility and preservation are clearly based on my own academic training and affiliation. This concern, however, prompted me to consider ways that I can participate in this dialogue in my limited capacity as a foreign scholar with limited resources. With the Middle Eastern examples and mentorship of my colleagues in the Scholars’ Lab (including the work and expertise of Edward Triplett), I jumped into the digital modeling and photogrammetry methods that have been so successfully implemented by larger art and archaeology projects to see what I could do personally. The resulting model and 3D print preserves the current state of the medieval Icelandic sculpture, but highlights both the potentials and limitations of these technologies for preservation and pedagogy.

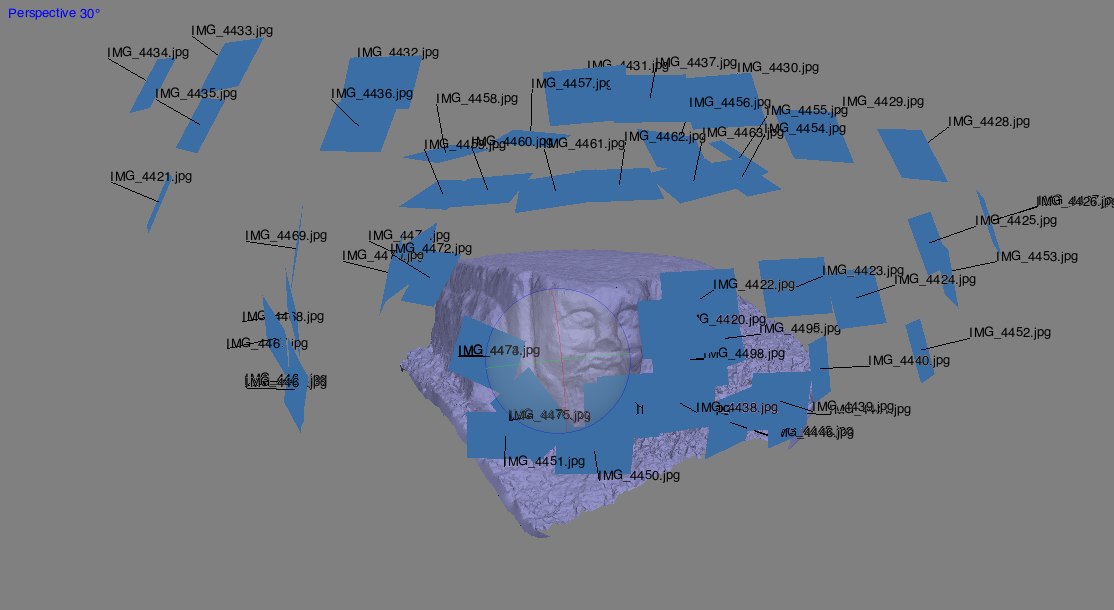

Armed only with my camera, I started by taking a number of photographs of the Hítardalur sculpture at varying heights and distances. My goal was to capture the sculptural relief and texture of the stone in as much detail as possible. After looking into different software, I invested in Agrisoft PhotoScan to compile a point cloud and build the mesh into a digital model. The software makes this easier than I anticipated and I was pleased with my early results. Because the sculpture was too heavy to lift myself, I was not able to photograph the base and, as a result, the digital model was open on the bottom. This is not a problem in itself, but the shell of this model would have been too fragile and had too many overhangs to 3D print properly. I exported the model to netfabb and meshmixer—both available for free—to make the model watertight (closed off on all sides) and reorient it to sit flat on a printer platform.

Position of the camera for the photographs used to make the Hítardalur model.

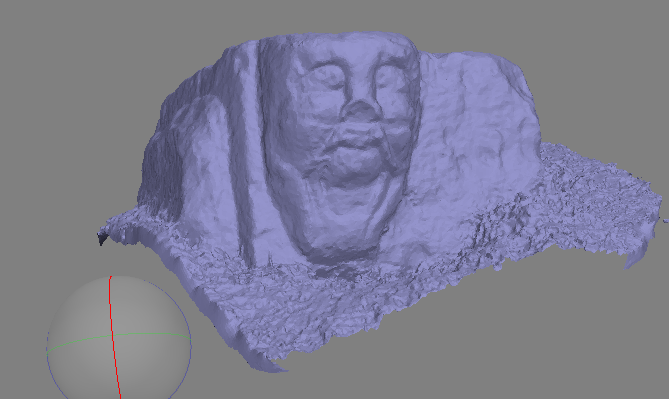

Finished Hítardalur model.

Finished Hítardalur model with texture added.

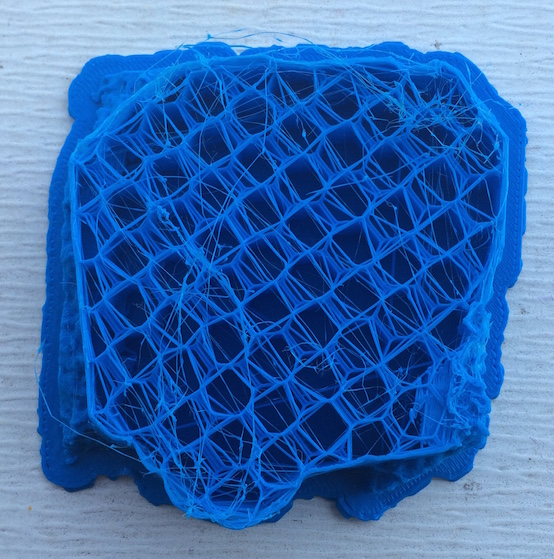

Printing the model had its own difficulties stemming from technical issues with the printers. After two failed prints on MakerBot’s Replicater 2 caused by a ‘glitch’ in the SD card, I reformatted the card and switched to the Ultimaker 2. Using the Ultimaker software, Cura, I shrank the model and set the slicer settings to a lower quality to print a quick, rough prototype. With this successful print, I increased the size and print quality to produce an approximately four-inch model.

First failed print of the Hítardalur sculpture using PLA and the Replicator 2.

Larger of the two succesfully printed Hítardalur prototypes. Printed using PLA and the Ultimaker 2.

With a successful model and print, I am now left with the burning question: So what? It is true that I have preserved the sculpture in its current form in case it ever disappears or further weathers away. The digitization also offers a better way to share and teach the sculpture in a multi-dimensional way across vast distances and languages. But the model’s value and efficacy are ultimately limited by its online accessibility. Museums and institutions are increasingly compiling vast open-access databases of digital images and models of their own collections, but an isolated model like this is easy to miss. This sculpture, for example, only appears in Iceland’s main archival database as an unnamed feature in a photograph of the farm. A model like this would likely need to be contextualized in larger project database, perhaps one dedicated to medieval, monastic, or sculptural Icelandic works, to increase accessibility and public interest.

The limitations of the 3D print are perhaps more obvious than the limitations of the 3D model. While the model has texture and can be shared online, the print varies in material, texture, color, weight, detail, and size from the original. Yet, the print is not necessarily meant to duplicate or replace the original sculpture. Its value lies in its ability to capture physical characteristics lost in digital form. Right now, the main way to teach artifacts is by digital photographs (or models when available). In some cases, such privileged photographs and models provide a chance to get a larger and more detailed view of an object than you can in real life (consider the zoom features in the Google Cultural Institute and Artstor). Still, nothing replaces the opportunity to experience an object or monument in context and in person. While the 3D print (especially the small prototypes) cannot reconstruct this experience, there is potential for 3D printing (especially when an artifact is printed in its actual dimensions) to mimic some of the physical features of the original that are lost in digital form. Students, for example, can interact with it as an object (rather than an isolated image) and analyze its forms in new and critical ways.

The opportunity to teach historical content while simultaneously training students to look, analyze, and think critically about the physical world around them through 3D prints is enticing. The next step in this project is to slice the digital model I have and print it as close to life size as possible. Due to the smaller size of the printers, this will require some experimentation with slicing the model, printing enlarged sections separately, and reassembling the parts. I have also requested an order for sandstone filament—which will better mimic the texture, if not the color of the natural sculpture’s stone. If this medium does in fact enhance pedagogical opportunities for material-based studies, there are almost unlimited opportunities for multiple disciplines to replicate real-world conditions and design more authentic teaching opportunities.

All attempted prototype prints of the Hítardalur model.