Printing Things That Print: A Miniature Hand-Press Project

For the past few months, fellow English PhD candidate James Ascher and I have had a small side-project going on in the Makerspace: printing a small, desktop-sized hand press, and getting it to work consistently. The model we found calls it a “Pocket Gutenberg,” but the idea of a small, hand-powered, personal “hobby” printing press is an historic one going back to Ben Lieberman and the “Liberty Press” – a history James will hopefully be posting about soon.

I want to talk about our experience making this thing and trying to get it to work. By putting it up here, I’m hoping it will be an example of the kinds of small exploratory projects that often become gateways into the growing scholarly field of remaking old technologies. On my end, I was also inspired by Jentery Sayers in his recent visit to the Scholars’ Lab (all the way from the Maker Lab at UVic) in which he discussed exactly this kind of project, though on a much larger and more rigorous scale (we have his talk in podcast form - check it out!).

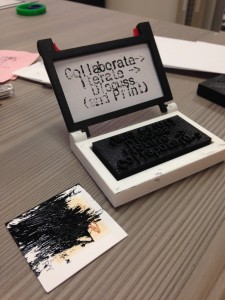

So what did we make? As linked above, we started by printing a desktop hand press. James then printed a plate with the motto, “Collaborate -> Iterate -> Discuss (and Print).” Using some ink we had meant for rubber stamps, we inked the plastic plate and gave it a shot – as you can see, what came out is readable (sort of) but not very pretty.

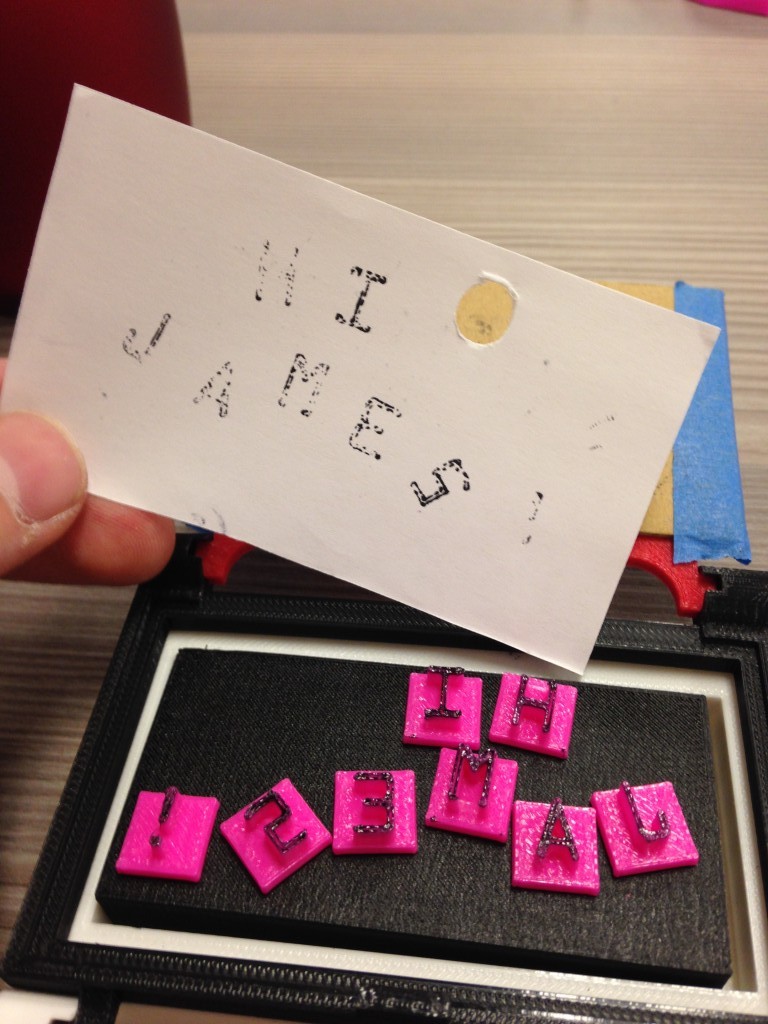

We jerry-rigged a few modifications (i.e. taped-on cardboard to raise and even out the paper) and then I printed out a single set of type from another model on Thingiverse, and sized it so that it would fit with our press. Printing with this type was a real pain as there was no way to keep them in place – a problem which, again, involved another series of jerry-rigged semi-solutions. Until we figured out a way to make this setting and pressing of type easier, our new press was going to be very limited in its applications.

As you can see, our goal in re-creation here wasn’t so much fidelity to a specific historical object as it was to explore the capabilities of an older technology (the hand-press) shrunk down in a new way to an individual desktop size that anyone could use on their own. Clearly, even this more modest goal led to a series of joyful problems. It turns out stamp ink is, well, mainly meant for stamps, and that not all paper is created equal. These may seem like obvious insights (and I’m sure they were to James, who knows much more about books as physical objects than I do) but for someone only recently beginning to learn about bibliography, textual studies, and the history of printing, these were practical concerns I had heard of but never had to really deal with before. And they are all things we are still working on with making our press work.

So why does this matter? In an earlier post titled “The Relevance of Remaking,” Sayers offers some questions that I found to be helpful in making meaning out of experiences with old technology. Two in particular – “From what materials was it [the old technology] made?” and “Through what measures was it deemed a success?” – were particularly revealing in our case. I was faced with problems like: what kind of paper works best when you are using plastic type? There’s a big difference between printer scrap paper we used originally and the softer paper, like from a cheap paperback, that we ultimately decided would work best. For that matter, I wondered what kind of paper works best using metal type – and what about differences in kinds of metals? What about different kinds of ink? What’s in “gel-based” stamp ink, anyways (as it reads on the back of the box)? When we tried it again with a small sample of the oil-based kind of ink used in relief printing (courtesy of Josef Beery), and the prints came out much clearer, even after multiple presses (despite being limited by the granularity of the Replicator 2 model and print).

These aren’t new problems – they’ve been around for as long as people have been trying to print things. And despite being surrounded by scholars interested in these fields here at UVa, it’s been very easy for me to take them for granted on a day-to-day basis – something I didn’t realize until trying to deal with them first-hand.

To summarize: What James and I are up to here is very small-scale. But while piecing together something from a 3D printer is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of remaking old technologies, it’s been a really good way for me to get my foot in the door – although the technology we’re building is not strictly historical, the problems associated with it are historic ones. Used in conjunction with the kinds of resources we have at the Rare Book School or Special Collections, this was a useful supplement to the study of books and book-making that I had the power to explore on my own. It certainly opened my eyes to a whole set of new questions in a physical, immediate way.

Regarding the bigger picture: we haven’t thought through every potential use of this press, or what scholastic infrastructure it will fit into as a project. In that sense it is surely subject to the “speculative condition” of purely exploratory research Bethany identifies and discusses in this enlightening post about speculative computing; but I would maybe liken our project even more to the kinds of projects she has described in another post as “too small to fail.” In this sense, even if our press ended up being useless, this particular failure could serve as “a concrete experiment” our peers can talk to us about and learn from. But this smallness and speculative-ness have their payoffs – most of what I ended up learning about remaking old technologies I came across because we had already started working with the desktop hand press. It was only after diving in and having problems that I had the impetus to see what others in the Maker community had to say about similar projects. What I found was really encouraging and left me with a whole bunch of new questions regarding our mini-project: when Sayers asks in another post, “Why Fabricate?”, that we consider “for which methodologies and research areas does material depth especially matter,” and when Devon Elliott et al. ask in “New Old Things” (an article cited in Sayers’ piece) for us to seek out “projects that allow us to imaginatively remake past technological artifacts and to experiment with past technological worlds,” the project acquired a new level of meaning for me.

I’m not sure if “make first, ask questions later” is a policy I would always encourage, but in this small-scale situation, given the time, resources, and encouragement to explore, following my interests ended up leading to not only to real, living problems, but also real opportunities to combine my work at the Makerspace with my work in literary study. Success! In this instance, exploration resulted in the surprise of discovering a new set of important questions already being explored by others.