Reading Grammar: First Attempts

I am not a grammar whiz. I couldn’t tell you off the top of my head what makes a verb transitive, much less how to identify a “nominal subject.” I haven’t taken a linguistics class or really thought all that much about the field past Saussure (the starting point for a lot of 101-level literary theory classes) and Chomsky (the point where mainline literary theory seems to diverge from linguistics). On the spectrum between descriptivism and prescriptivism I’m an apathetic descriptivist. But in writing the last couple chapters of my dissertation, I suddenly found myself brushing up on the basics. I’m taking something that I’ve known by feel for 20 years and trying to understand a bit more about how it’s formalized. One of the tools I’ve been using is not really from linguistics but rather out-of-date writing pedagogy.

In my first post I gave some backstory for my fellowship project studying grammar structures in Gertrude Stein. I’m going to use this post to show how I’ve implemented one piece of the puzzle. What I think is really interesting about this example, from a digital humanities perspective, is the way that computation can resurrect some old forms or inquiry that people have neither the time nor inclination for. I’d struggle mightily to diagram a single sentence by hand, but I’ve generated hundreds of diagrams while writing about Stein. They have changed how I read them. With all the big claims about what machine learning does to our experience of the world here’s a very minor, very specific one: reconstructing an old pedagogical task in order to inhabit an old way of thinking about composition.

Like I mentioned above, I haven’t spent a lot of time thinking about how grammar structures are formalized. This is probably in large part because I’ve been word-processing digitally more or less since I started writing. I’ve always had those squiggly underlines to tell me when I had something wrong with my grammar. From the late 1800s to the 1960s or so when the practice began to fall out of fashion, American schools had students drill “sentence diagrams” in order to learn writing and the basic tenets of grammar.1

Reviving the Grammar Tree

So what do sentence diagrams actually look like? There’s no one standard, even though an 1877 textbook by Alonzo Reed and Brainerd Kellogg was the most influential in writing pedagogy of the late 19th century. A lot of the hand-drawn diagrams look something like this:

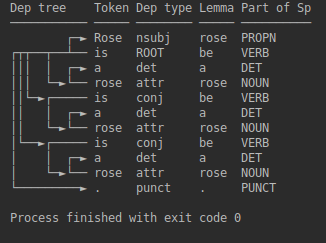

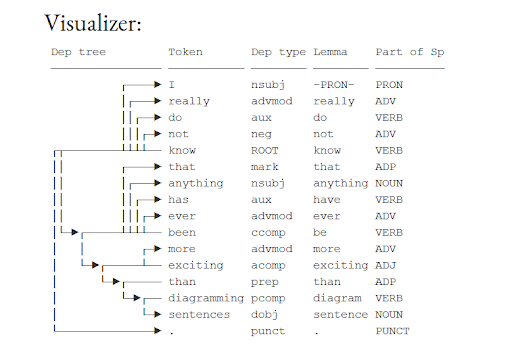

It’s safe to assume Stein would have been creating diagrams that looked similar. I’ve been generating diagrams using the natural language processing package SpaCy for Python and a module called explacy. Explacy ‘prints’ out grammar trees in a monospaced font as a low-tech way of generating grammar diagrams of various length.

For a while I was using these tools locally, but eventually it seemed worth finding a way to put them online. You can try out a (very rough!) demo of the sentence parser here.

I started thinking about sentence diagrams because they appear to have been quite formative to the young Stein. If other students dreaded the rote (and as it turns out fairly useless) “grammar school” task, Stein loved the systematic approach to language:

When you are at school and learn grammar grammar is very exciting. I really do not know that anything has ever been more exciting than diagramming sentences. I suppose other things may be more exciting to others when they are at school but to me undoubtedly when I was at school the really completely exciting thing was diagramming sentences and that has been to me ever since the one thing that has been completely exciting and completely completing. I like the feeling the everlasting feeling of sentences as they diagram themselves. (Lectures in America 210-211)

When I use modern natural language processing technologies to generate sentence diagrams, I get to share in Stein’s act of “completely completing” an analysis the skeleton of a sentence. Neither do I feel like I’m missing too much by automating the process–even Stein, who was drawing the diagrams by hand, phrases the activity as something inherent in the language–sentences “diagram themselves.”

Participating in the act of diagramming gives me not only a glimpse of how Stein and her American contemporaries would have been trained to think about composition, but also a better technical vocabulary for closely reading the mechanics of Steinese. William H. Gass once wrote about seven pages closely reading Stein’s use of the word ‘the’ in a single sentence from Stein’s Three Lives. It’s even an interesting read! Gass’ eye for the subtleties of ‘the’ is a skill that only comes with a super-analytic approach towards language mechanics, drilled from childhood. I frankly don’t have the stamina or skill set for that sort of reading, but by crunching the numbers with a computer rather than working by hand, I can at least borrow the correct terminology. For as often as digital humanities gets branded as being about new methods, sometimes it’s worth simply resurrecting the old. You learn something about the linguistic world your subjects lived in, and pick up some maneuvers of your own along the way.

Endnotes

-

Grammar was always important to pedagogy, a component of the lower “trivium” within the classical hierarchy of the liberal arts, alongside logic and rhetoric. But Americans, apparently, took the idea of studying grammar quite literally. ↩