Rebooting Graduate Training: An MLA Roundtable

I gave the following talk at the 2013 MLA Convention in Boston as part of an excellent roundtable organized by Paul Fyfe, who has also collected a number of resources in a Zotero library. The wide-ranging presentations sparked many thoughtful questions that I hope will lead to continued discussion about the ways that graduate training could be modified for the good of students, the discipline, and the public. Some of the slides are taken from my earlier presentation on SCI’s survey on career paths for humanities PhDs (a full report of which will be available later this year).

I’d like to take a step back from the question of how to reboot graduate training, and think instead about why we need significant change. Lately, some long-standing issues in higher ed, such as employment rates for PhD holders, seem to be receiving renewed attention that will hopefully set the stage for broad-based action. Some of these recent developments and articles include:

-

The report on the 2011 Survey of Earned Doctorates, which presented the grim fact that 43% of doctoral recipients have no job or postdoctoral plan upon receiving their degree;

-

A proposal at Stanford, designed by past MLA President Russell Berman and other faculty members, to dramatically reduce time to degree and to reform many aspects of humanities education; and

-

Current MLA President Michael Bérubé’s talk at the Council of Graduate Schools’ annual meeting, in which he discussed the critical importance of reforming graduate training.

Note: I’ve written about the items above in more detail in a recent ProfHacker post. The post includes a broader range of links to other write-ups on these topics.

There are numerous other examples of ongoing work of this nature, such as the MLA’s Task Force on Doctoral Study in Modern Language and Literature, which hosted an excellent discussion on the topic at the convention.

These conversations help to amplify current work being done by a number of individuals and organizations, at the Scholarly Communication Institute and elsewhere. My work with SCI has been deeply informed by the essays at #Alt-Academy, for instance, an open-access publication of Media Commons that explores the many issues related to the sometimes tense relationship between scholarship and professional directions. Of course, I’m also indebted to the extraordinary work and people of the Scholars’ Lab, which has housed SCI for the past few years.

Over the past several months, SCI has embarked on a study of career preparation among humanities scholars working in alternative academic careers, and we are also developing a network of innovative humanities programs to highlight possibilities for reform (more on that in a moment).

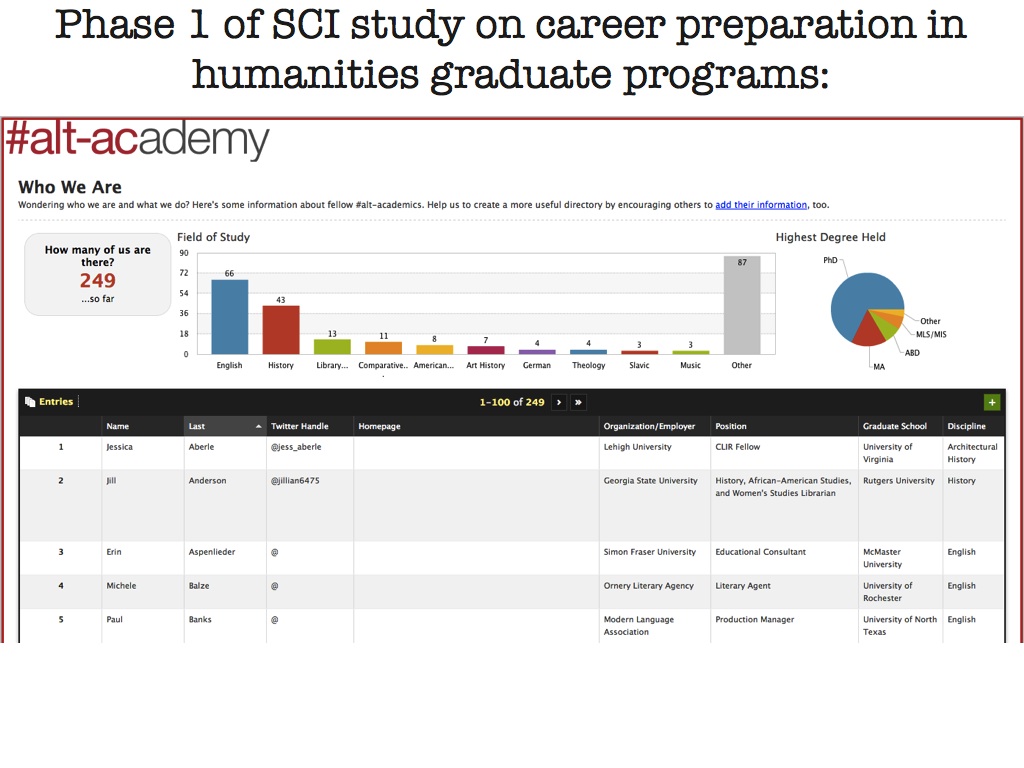

The goal of SCI’s study was to move from anecdote to data in the conversation about alternative academic careers. All of us know stories of the victories and challenges of pursuing an intellectually stimulating career beyond the tenure track, but there was little data to back up the narratives.

With that in mind, the study had two main phases. The first phase, which was public and exploratory, involved creating a public database where people comfortable enough to publicly identify as “alt-ac” practitioners could add themselves to a loose community of peers. The second phase of the study consisted of two confidential surveys.

We built the study within the framework of the #Alt-Academy project in part to leverage the energy of existing conversations. While “alt-ac” isn’t a crisply defined term, many people have found it to be an incredibly useful umbrella under which they could gather to talk about the kinds of satisfying careers that can be found outside the professoriate.

Trends among the nearly 800 responses we received to the main survey reveal a strong misalignment between the expectations of graduate students and the realities that they face upon completing their program.

As may be expected, a large majority of students enter graduate school expecting to pursue careers as professors—a total of 74%. What is perhaps more interesting is their level of confidence: of that 74%, 80% report feeling fairly certain or completely certain that this was the career they would pursue. Keep in mind that the survey respondents are all working outside the tenure track.

These expectations are not at all aligned with the current realities of the academic job market, as we know, and the urgency of finding a remedy to the lack of transparency is compounded by the rising amounts of student debt that burden so many graduates.

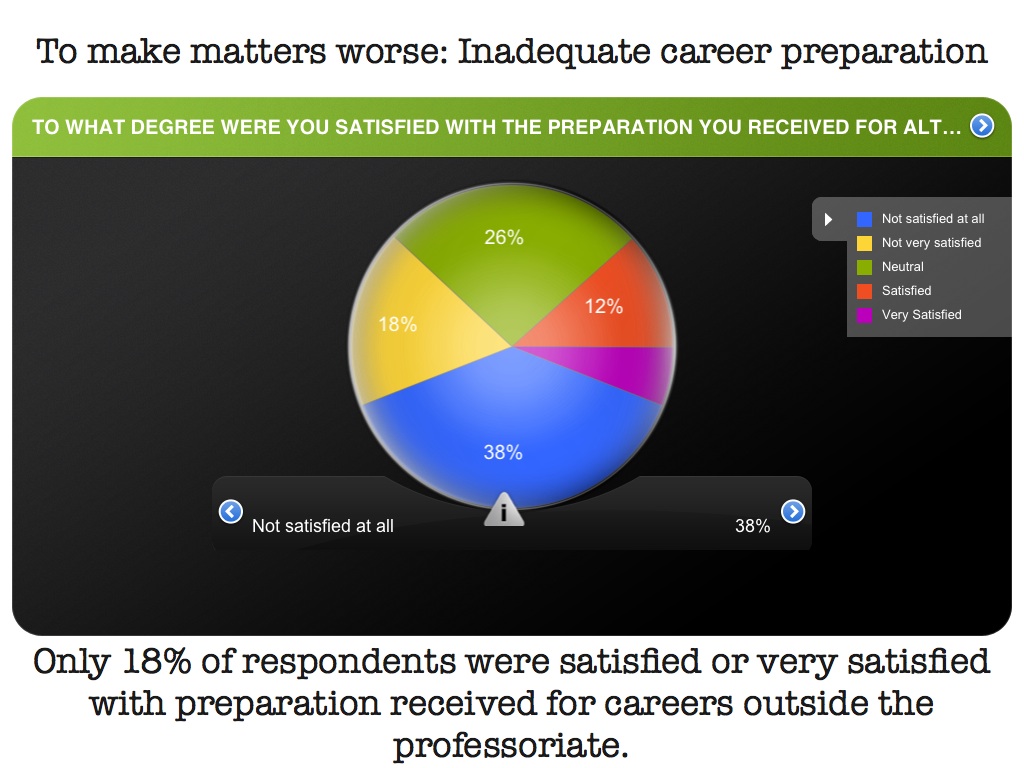

Deepening the problem, students report receiving little or no preparation for careers outside the professoriate, even though we’re at a moment when the need for information about a variety of careers is most acute.

Only 18% reported feeling satisfied or very satisfied with the preparation they received for alternative academic careers. The responses are rooted in perception, so there may be resources available that students are not taking advantage of—but whatever the reason, they do not feel that they are being adequately prepared. Again, this probably comes as no surprise, but it does reveal that we have significant room for improvement.

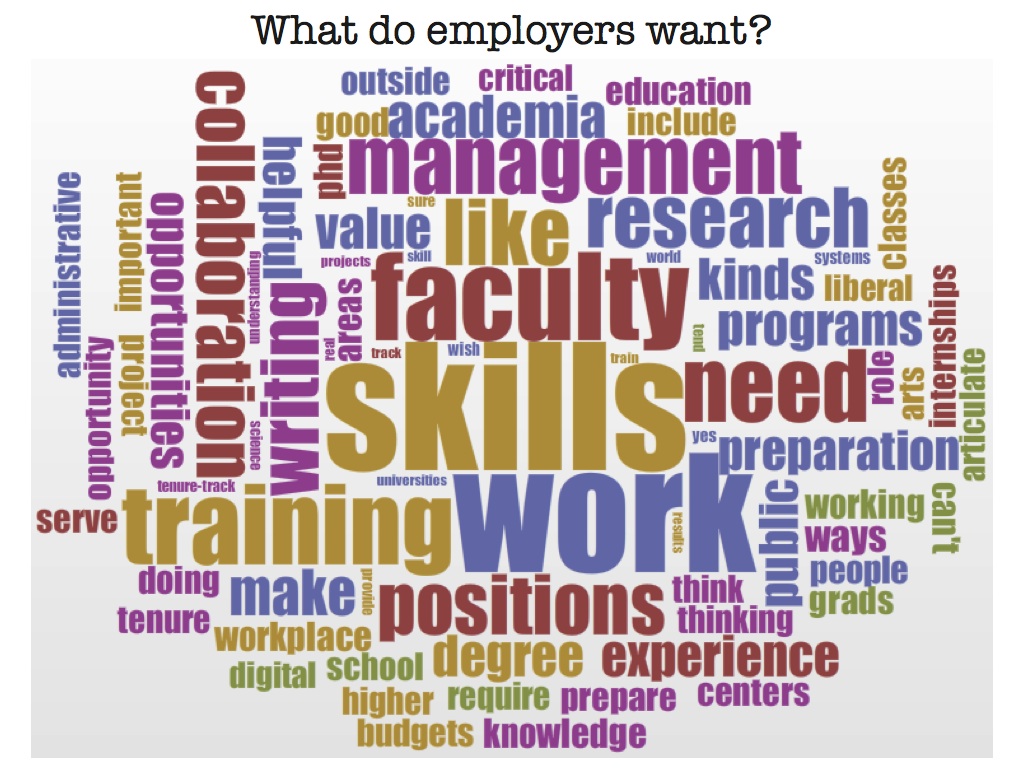

To give you a small taste of perspectives on the other side of the employment equation, here are some of the kinds of things employers indicate they would like to see:

Some specific skills come up frequently, including project management, the ability to work with and manage people, and written and verbal communication with a variety of audiences. Beyond that, employers mention a number of broader aptitudes, like a commitment to public engagement and an ability to adjust to the culture of different types of workplaces.

The good news is that all of the elements that employers seek would also be hugely beneficial for those grads that do go on to become professors. By rethinking their curricula in such a way that students gain experience in things like collaborative project development and public engagement, departments would be strengthening their students regardless of the path they choose to take.

UVa’s Praxis Program is designed as one of several new initiatives that help to assess needs and opportunities, develop and articulate new models, and foster the growth of collaborative networks among relevant institutions and individuals.

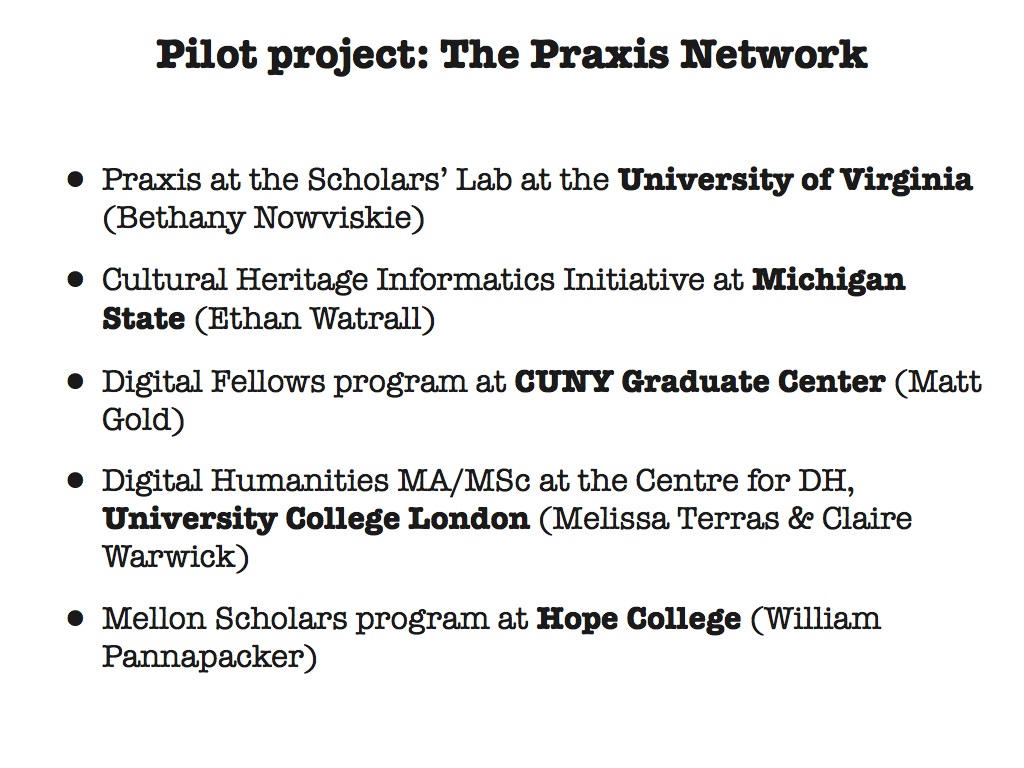

To help showcase strong models of reform, SCI is now developing the Praxis Network: a network of several existing programs that have developed innovative models of methodological training along the lines of the Praxis Program at UVa.

We anticipate that many programs that want to make changes will want to look to existing models for guidance, and by highlighting a handful of differently-inflected programs, we can bring together some patterns among them, while also underscoring the unique idiosyncrasies of each. In addition to sharing information with the public, we hope that the network will enable increased possibilities for communication and collaboration among the participants of each program.

One thing seems clear: the persistent myth that there’s nothing but a single academic job market available to graduates is damaging, and extricating graduate education from the expectation of tenure-track employment has the potential to benefit students, institutions, and the health of the humanities more broadly.

However, as long as norms are reinforced within departments—by faculty and students both—it will be difficult for any change to be effective.

Low tenure-track employment rates are not a new problem, but as the survey responses show, departments by and large are not succeeding at providing accurate and realistic information to their students.

For change to be possible, it’s essential that institutional norms and measures of prestige shift in favor of highlighting successful outcomes across a broader spectrum of possibilities. SCI hopes that our current work will help begin to rise the tide of transparency and innovation.