Starting off on the Right Foot (Part One)

This post is the first in a series that contextualizes my current project, Digital Skriker, within a larger tradition of studying and archiving stage movement. My project explores both the theoretical cruxes and archival possibilities enabled by robust and increasingly accessible motion capture and virtual reality technologies using Caryl Churchill’s play, The Skriker (1994) as a case study. I’m interested not only in how these technologies might change the way we think about documenting stage movement and gesture, but also how they may be used to create modes of (posthuman?) performance.

Nothing is more revealing than movement,” wrote Martha Graham, legendary choreographer and pioneer of modern dance. “The body says what words cannot.” Her view that dance could reveal human interiority is shared among many practitioners in the performing arts, as is reflected in the many innovative projects (both analog and digital) that attempt to find better or more useful ways to “read” or archive movement. My work in this field builds on my experience as a theatre director.

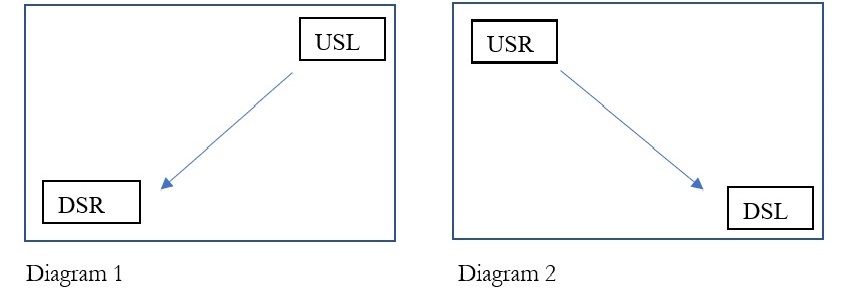

I once attended a directing workshop that introduced me to the arcane art of composing stage pictures. The facilitator had participants observe volunteers move in two different ways. First, a small group entered the stage area from upstage left and moved to downstage right (Diagram 1). The group then repeated the movement, this time starting from upstage right and moving downstage left (Diagram 2). The facilitator then asked the audience which movement path seemed more threatening and the group, virtually unanimously, replied that watching characters move from upstage left to downstage right (Diagram 1), or moving laterally from the audience’s right to left, conveyed more menace. How strange that something as simple as watching someone move from right to left would be interpreted so similarly by a group of theatre practitioners!

This logic—that some areas of the stage and some movements across its surface have connotations—is not unique to contemporary theatre, either. We may also look to acting manuals from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that align certain movements and postures with certain emotions, Bacon’s A Manual of Gesture which relates hand gestures to public oratory, or the choreography of classical ballet for examples of embodied semiotics. Furthermore, a 2012 study at Cleveland State University that looked at lateral movement in film provides data to support the idea that characters moving from right to left had a “negative affect,” making audiences feel more anxious and uncomfortable.

The researchers at Cleveland State made some conjectures as to why their participants, like those in my directing workshop, were more comfortable with left-to-right lateral movement. They suggested that perhaps the dominance of right-handed people has made the left-to-right pan vastly more common in film. Audiences, they suggest, may divide the screen into “good” and “evil” sides according to the pervasiveness of Christianity in Western Culture; it is far better for one to sit at the right hand of God than the left. I wonder, too, whether or not our perception of lateral movement is conditioned by the way that we read. In English, moving our eyes from left to right would be more natural than moving from right to left. Our interpretations of human movement seem, like our other interpretations, to be culturally and historically contingent.

Further examples of this can be found in the ways that some theatre- and film-makers also use directionality to categorize certain movement as “strong” and “weak.” For example, in Understanding Movies, Louis Gianelli posits that characters perceived to be moving in an upward direction (due to the way that camera pans) seem stronger or more dominant, while downward movement appears weak or subservient. Theatre directing is full of these kinds of strange adages as well, and directors often speak of composition as filmmakers describe the mis-en-scene, using lines, levels, and spacing to create emphasis.

This is all to say explicitly something that choreographers, actors, and directors understand intimately: movement is an essential part of theatrical expression. We find meaning in and interpret it, as we do the social gestures we make and observe in our everyday lives. In Digital Skriker, I’m mulling over the implications of motion capture technology on the documentation (and potential re-creation) of performance. The Cleveland State study provides empirical evidence that confirms existing wisdom about film composition; I wonder to what extent motion capture can do the same for theatre?

In the next post in this series, I will discuss the limitations of thinking about movement and composition in the terms I’ve outlined and explore other systems for documenting movement and digital projects that play with stage movement, choreography, and motion capture. Stay tuned, friends!