What I’ve learned from my Kindle: part II, and other thoughts on Prism and markers

A while back I posted what I thought would be the first of two blog contributions about my (relatively) new Kindle—I figured that in the second of these I would address the way the “pages” of a Kindle book work and perhaps offer some thoughts on how I think Prism “pages” (or whatever we’re going to call them) should work. Since then, as will be made clear by the many posts immediately preceding this one, there has been a flurry of conversation about a cluster of topics all related to how the marked-up documents should appear (in theory) in Prism. Some of this began before our meeting last week, but doing the transparency exercise presented us with a whole new set of problems to consider. Though I think a few of my original reflections on the Kindle are still worth posting, I’d also like to (briefly) address some of the bigger questions I’ve had from the beginning of this project about what kind of marking our crowd-sourced crowd will be able to perform on Prismed documents.

I left you, dear reader, with quite the cliffhanger in my last post. I had downloaded a free Amazon Kindle edition of Loss and Gain, and was prepared, cup of tea in hand, to devour some John Henry Newman. What happened next?

To keep things simple, I’ll just say that I still prefer books, and perhaps even print-on-demand books, to the Kindle. In her comment on my first Kindle post, Brooke mentioned some of the same problems I encountered, the most frustrating being the difficulty not of making comments on the text but of using them later. The general discomfort I felt during our discussion group when I was not able to page through the physical book is, of course, something one must get used to if one wants to use e-texts, but I do second Brooke’s wish for page numbers at the very least (the book I was reading was organized by “locations,” whatever those are. I’m afraid I didn’t do much Kindle research before I began this adventure). But these objections mostly arise from my preference for the physical form of the codex. The codex is an excellent machine, not ever quite satisfactorily reproducible digital form. An e-reader is not, and cannot be, a codex.

Of course, Prism is not concerned with the codex, or with written comments. The only way to “comment” on a document in Prism will be to highlight it: to color it. You aren’t allowed to explain yourself. The project wouldn’t be half so exciting (or provocative) without this limitation.

Strangely enough, there is something similar going on in Kindle e-texts.

As I read Loss and Gain, I began noticing that some sections of the text appeared to be underlined, and at the beginning of such sections, a grey subscript note indicated the number of people who had previously highlighted that phrase or sentence or (in some cases) paragraph. I next discovered that through the menu I could easily access what Kindle calls the “popular highlights” in the novel all at once. There are no comments attached to these highlights: you merely know that some anonymous group of thirty-six people all found this or that sentence interesting enough to underline. Perhaps Newman has something to do with it, but I thought the vast majority of these obviously favorite segments would do well on a greeting card: “we must measure people by what they are, and not by what they are not;” “our strength in this world is, to be the subjects of the reason, and our liberty, to be captives of the truth;” “in the choice of friends, chance often does for us as much as the most careful selection could have effected;” etc. In any case, this did get me thinking a bit more about what I’d like to see from Prism.

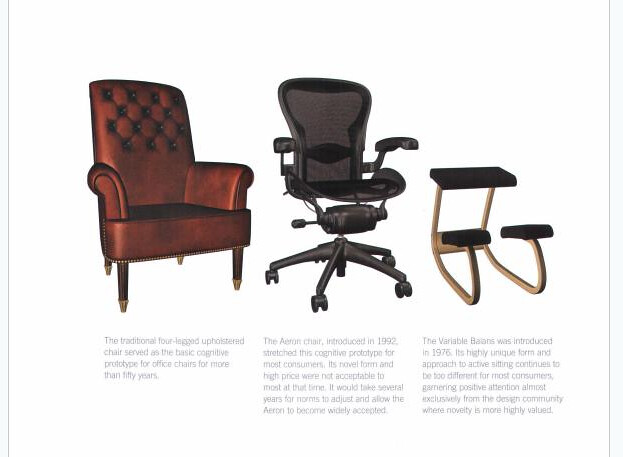

The only way to “mark” a text on the Kindle is to put your cursor in front of a word and then “highlight” until you reach the end of your section-of-interest. I could be wrong, but I had the impression that many on the Praxis team envisioned Prism working in a similar (linear) fashion—that is, before we got out the markers last week. After all, how could one possibly “highlight” something like this and achieve a satisfactory result?

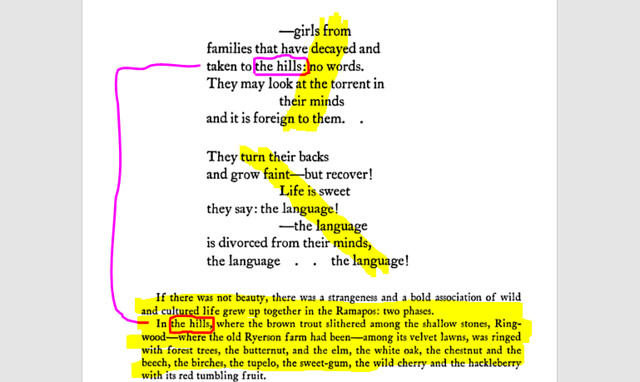

Ed’s transparency exercise involved an even more complicated image than the one above. But even documents we consider to be more “text” based, or prose-y (such as pages from novels or poems), do not necessarily call for straightforward, linear highlighting. Consider the following excerpt from William Carlos Williams’s Paterson, which I’ve taken the liberty of marking up with my snipping tool:

Alex’s post demonstrates his obviously more sophisticated understanding of the technical limitations we’re up against as we try to build a basic working version of Prism, but I figure that as long as Wayne keeps saying “right now, the sky’s the limit,” it can’t hurt to push things a little bit!