Harlem in Lynchburg: Stories about Space in a Summer Internship and the Jim Crow South

On July 25, I presented a paper that I had proposed in November for the ACH 2019 Conference in Pittsburgh, long before I had even heard of my co-author, Aleyshka Estevez Quintana, an English major at the University of Puerto Rico. It was too late to change the program, and anyway Aleyshka, one of the small group of undergraduates of color sponsored for a summer of research training under the Leadership Alliance Mellon Initiative (LAMI), couldn’t have come to Pittsburgh because she was presenting her own research on electronic literature and geolocated narratives at the LANS national conference. Only because I had the good fortune to work with Aleyshka as my mentee in June and July did I have anything more than wishful thinking to present in Pittsburgh. Thanks to Aleyshka, and the willing experts in the Scholars’ Lab, the future tense could shift to more confident “we have prototyped” our approaches to augmenting the collections associated with Anne Spencer, the Harlem Renaissance poet.

“Harlem in Lynchburg: Anne Spencer’s House and Garden Project” was slated in a short-paper session, “The South,” with two excellent projects from Coastal Carolina University and their Athenaeum Press: “Trans Voices of the South,” by Alli Crandell, Tripthi Pillai, Shonte Clement, Joshua Parsons (an oral history and printed collection of essays); and “Telling Hampton’s Stories: Design and Production of Virtual Hampton’s Spatial Vignettes,” by Susan Jean Bergeron and Crandell (a reconstruction in Unity of a former rice plantation). The Coastal Carolina teams included undergraduate presenters of the results of pedagogical/research teamwork on race, gender and sexuality, geography/space, and interactive narratives—just what our project aspires to. I wished Aleyshka could have met the undergraduates, Shonte and Joshua, who presented on “Trans Voices,” but I tried to channel Aleyshka’s inventive research in my talk.

So, to give thanks where thanks are due, and share thoughts on what we hope to do. The Lynchburg residence of the Harlem Renaissance poet Anne Spencer (1882-1975) is a gem of vernacular architecture and garden design. It is curated (tours by appointment) by a grand-daughter of the poet, Shaun Spencer-Hester, with a foundation and board. The garden has been restored to peak condition and is open to the public at any time. Books of photographs and videos depict the landscape architecture and the house. The website links to a highly usable virtual tour of the house by Virginia Humanities (Google maps). So this is not a hidden archive or a hidden figure. Anne Spencer hosted and corresponded with many of the most famous African Americans of her day, and her poems appeared in all the notable anthologies in the decades of the Harlem Renaissance; with the rise of African American and feminist studies, she was again sought out. Although scholarship on Spencer is scant, there are full-length biographies by J. Lee Greene (1977) and Noelle Morrissette (just now seeking a publisher); a memoir by Spencer’s son, Chauncey, and another by Carrie Allen McCray, the daughter of Anne Spencer’s close friend Mary Rice Hayes Allen, with whom Spencer co-founded the Lynchburg branch of the NAACP in 1919.

On June 24, Aleyshka and I, with librarian Melinda Baumann, visited the museum and talked for two hours with Shaun Spencer-Hester. On another day, Aleyshka and I went through several boxes of the Spencer papers in Special Collections. After a workshop that Jeremy Boggs gave to LAMI students about narrative software tools, Aleyshka quickly laid out a sequence of events, places, people, and literary works using the knightlab.com Timeline JS3 software, posting it on her blog. We both read the Greene biography and I read the memoir, Who Is Chauncey Spencer? and McCray’s Freedom’s Child, which includes interviews in the 1970s with Anne Spencer. My work on the timeline included research on facts, adding “groups” (themes), images, events, and other material, and editing. We early on conceived of linking biographical annotations with rooms in the house and other sites in the virtual tour. As we worked, we asked Jeremy, Drew MacQueen, and Chris Gist for help, and they were always ready to step forward. Drew, especially, met with us for hours as we worked through some of the snags in the latest version of arcgis StoryMaps, where we imbed the Timeline. Both data and design have a long way to go; we will continue to select and shape the stories we tell. The start of Anne Spencer: Harlem South will always be shaped by Aleyshka Esteven’s willingness to take on this challenge and run with it. She is one of the best student researchers I’ve ever worked with, and I’m sorry she’s now gone home to Puerto Rico. I think it’s fitting that her blog juxtaposes comments on the current demonstrations in Puerto Rico with our project on the spaces that African Americans made for themselves in twentieth-century Virginia. On the day of my talk, the news spread that Gov. Ricardo Rosselló resigned.

In the coming school year, we hope to have some UVA undergraduate interns to engage with the project. Meanwhile I will be reaching out to experts, here and elsewhere, on Lynchburg and the Harlem Renaissance. We will work out an agreement for collaboration and permissions with Shaun Spencer-Hester, as we apply for funding. At this point, the project postpones common practices of literary DH, from digital editions to textual analysis, to experiment with maps and timelines. We plan various approaches to amplify and complement a cultural-heritage site, uniting cultural studies with digital tools.

We don’t want to make the wrong moves, when a research university appropriates indigenous materials or claims discovery of heritage that has its own substantial preservation. But there is a collaborative role to play, and a great deal of room for amplifying the meanings of this site and archive. The papers in UVA’s Special Collections are still largely inaccessible to the public. And the more you know about this biographical topos (place, topic) the more interesting, rare, and important it is. It is one of a handful of museums dedicated to an African American woman, and perhaps the only one in the former home of an African American woman writer. It serves as a salon, in the French sense, and a sanctuary within Jim Crow, a triumph of real estate within disenfranchisement.

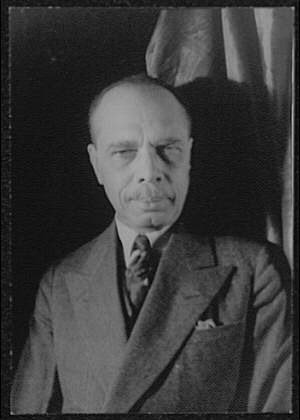

James Weldon Johnson

In my talk, I emphasized two main points: The Domestic is Political; and Harlem Is in Lynchburg. That is, the very spatial differences, points or boundaries, that our study marks are transactional and unstable. With African, European, and Native American antecedents, this is an elite salon, as Wordsworth’s Rydall Mount is elite; Lynchburg newspapers record that any notable visitor in Lynchburg, white or black, visited at the Spencers’. We’re hoping not just to repeat the list of the famous who came there, but to exhibit themes that reveal more than the sweet lady poet in her home and garden. The writing is literally on the walls (she wrote drafts on anything at hand) and every design shows that the place is a co-production of Anne and Edward Spencer and friends (artwork and gifts, letters and other effects on display). We’re interested in who came there, who left, and why; it was a center in a cultural movement associated with the New York hub, Harlem. James Weldon Johnson, for instance, stayed there because he was the Field Secretary of the NAACP, saw Spencer’s poetry in the house, and ensured that editors saw it: a political/literary/personal relationship.

Aleyshka and I were coming to this material almost simultaneously; I relied on her organizing the people, events, selected photographs and sites. In future work, Aleyshka’s findings will influence what Scholars’ Lab staff and I work on. I would be delighted if Aleyshka were to decide to apply to UVA! She’s planning to get an MFA first, to work on her experiments in digital literature.

I won’t carry on in this post (I could really carry on) about the discoveries and potential directions for more research. But for tantalizing sample themes, consider:

- Exoticism or Resistance?: Anne Spencer dressed as a Native American; “Japanese” furniture and wallpaper in the house

- Friendships and LGBTQ Flight from Lynchburg: Amaza Lee Meredith,lesbian African American architect; Murrell Edmunds, white writer from Lynchburg, a gay UVA alumnus who moved to New Orleans and urged us to acquire Spencer papers

- Integration and Separatist Equality: son Chauncey Spencer, who inspired Tuskegee Airmen and helped integrate the airforce, was accused (wrongly) of being a Communist and was ostracized before he held positions in California and Michigan high schools and police departments; he argued against Black Studies in the 1970s. Anne Spencer was skeptical about integration.

- African American Travel and Leisure: Happyland Lake and Harrison Theater, in Lynchburg; Azurest North, Sag Harbor, Long Island