Mimesis and Computers

“Computers are inherently dumb.” I hear this all the time, even from folks in computer science. I like to think of them as marionettes.

After Wagner called for a Gesamtkunstwerk, many European artists and thinkers reacted strongly to it (Nietzsche being the most famous case). This reaction eventually led to a modernist distrust of theater in general, and of human actors in particular. Think for example of Bertolt Brecht’s Verfremdungseffekt. Somewhere in between Wagner and Brecht, the English artist Edward Gordon Craig suggested that human actors should be replaced by marionettes. As you can imagine, this did not go well with the actor’s guild.

I hear echoes of those debates and cultural shifts in our moment, when computers are starting to resemble us more and more. Computers don’t replace us always in the way that machines replaced farmers or smiths, although there are still parallels between ours and the anxieties of the industrial and agricultural revolution. And just like machines then generated monstrous forms of mechanized human labor, computers do the same (If you don’t believe me, ask any of my students for Project Tango). However, there is another anxiety I see which is not necessarily that of machine iteration replacing familiar mechanical tasks with unforeseen ones. I’m talking about our fear of marionettes. Even more specific, the fear that we will confuse the marionettes for human beings.

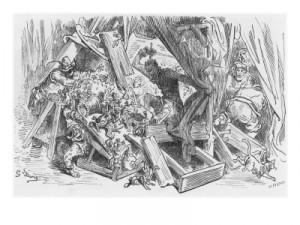

Quixote fights the puppets

The true marionette is always controlled by a human, so are computers… ultimately. We ventriloquise through them, and they only talk back to us according to our ridiculously precise instructions. I’m not talking about Bina48. She’s kind of creepy. I’m talking about the ways in which a google search acts like an operator at the end of a 411 call; or the way that netflix suggests what we might like.

There are two approaches to figuring out what counts as a title in a large repository: we can tag it, or we can write an algorithm that does it for us. Don’t worry, we’re not there just yet. At some point that meta-data might pass the Turing test. If it does, by definition, users will think a human did the work… but wait. When it does, by definition, users will think a human did the work… but wait…

Prism is not really interested in how humans might be fooled by the marionettes more than it is in how we can fool the marionettes to behave like us. Sometimes that line is blurred. The ‘text mining’ component, as I have understood it, seems like the bastard child of natural language processing and web crawling. The goal here is not to count words (although that is a time-honored human activity), but to abstract semantic relationships that can be used to query large data. When we Google something, we are doing something akin to that, except we never think Google is run by a million efficient munchkins. When we start getting results for our perhaps-to-be Prism queries, we use those results in public at our own risk. That there will always be Quixotes in the audience… well…

Take home tweet: Even if we replace actors with marionettes, the plot stays the same.