On Complexity

When I wrote my first “real” code for a website, things were a lot simpler. I was taking SGML TEI files and running them through a DSSSL generator to create static HTML files. It was pretty straight-forward: I would tag a document, cross my fingers that it would validate, then run a script that would regenerate the entire site. CSS hadn’t been invented yet, so the site layout was handled in a table, and really the only way ‘discover’ the content in the site was to actually read everything that was contained in the ‘site.’ There was a team of five of us attempting to figure all of this, and generally the feature that won was the one we figured out first.

Skip forward a decade, and I now use a dizzying array of frameworks, tools, occasional tricks for any given project. As a case in point, look at any of the plugins our group have been developing for Omeka: we write the code in PHP, then use tooling written in Ruby, Java, and nodeJS. The real question of how to explain exactly what goes on in a modern web-based application is one I, personally, struggled with over the last year. There’s typically a database tier, a presentation tier, business logic, external libraries, and framework idioms and vernacular to explain. Even once you get an OK grasp of how a programming language functions, the jump from making a simple loop to a building a web application that ‘works’ is quite a feat. On top of this, add the softer skills of translating the intent of a feature into actual code and coordinating changes with multiple people working in the same places in the code base, and even what it means to work together in a productive way can be challenging.

Just to give you an idea of the complexity of the things swimming around in the various heads of the team that developed Prism, this is a visualization of the library dependencies in the project:

With a system this complex, true collaboration is needed, with different people taking on different tasks and responsibility for sections of the code, and working together.

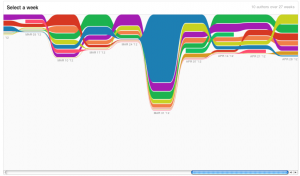

You can see in this impact graph that there isn’t just one person making all the changes. You also see experiments that were started (and ended). Not only are experiments waxing and waning, there is also no single contributor who dominates the code base. I feel this is an exceptionally important take away from this last year; no one collaborator on Prism would have been able to execute this project alone.

When I reflect on the changes in how web applications are developed since I started in this kind of work, I see no real method to the madness. It was a wild-wild west, and we figured out what we needed to (often making what in retrospect were horrible technical decisions) in order to ship our sites. But things were much simpler: browsers were much simpler, almost everyone had a dial-up connection, and you could really figure out how someone implemented a cool feature (like an ‘under construction’ gif) by looking at the source code. Fast-forward a decade, and there are many more balls to juggle. Viewing the source code for a web application probably won’t get you very far.

Along with understanding how software is put together, there are the more frustrating elements of development. Sometimes approaches just don’t work, or they work in one environment, but not another. Dealing with these issues, and being able to adapt or completely rethink a plan of attack, is a skill in itself. Being able to pivot technically, and rethink a given approach (or even better, knowing where that line is) is one of the more difficult skills to learn. As I’ve watched the graduate students in our Praxis Program over the last year, I’ve seen them transform how they think about the problems they encounter, applying the same analytical skills they use in their scholarship in their coding practices. My hope is that the practice in critical thinking and scholarly argument with which they learned to imbue the actual code base of Prism will help them as they go out in to the world as scholars – and will continue to serve them in the future.