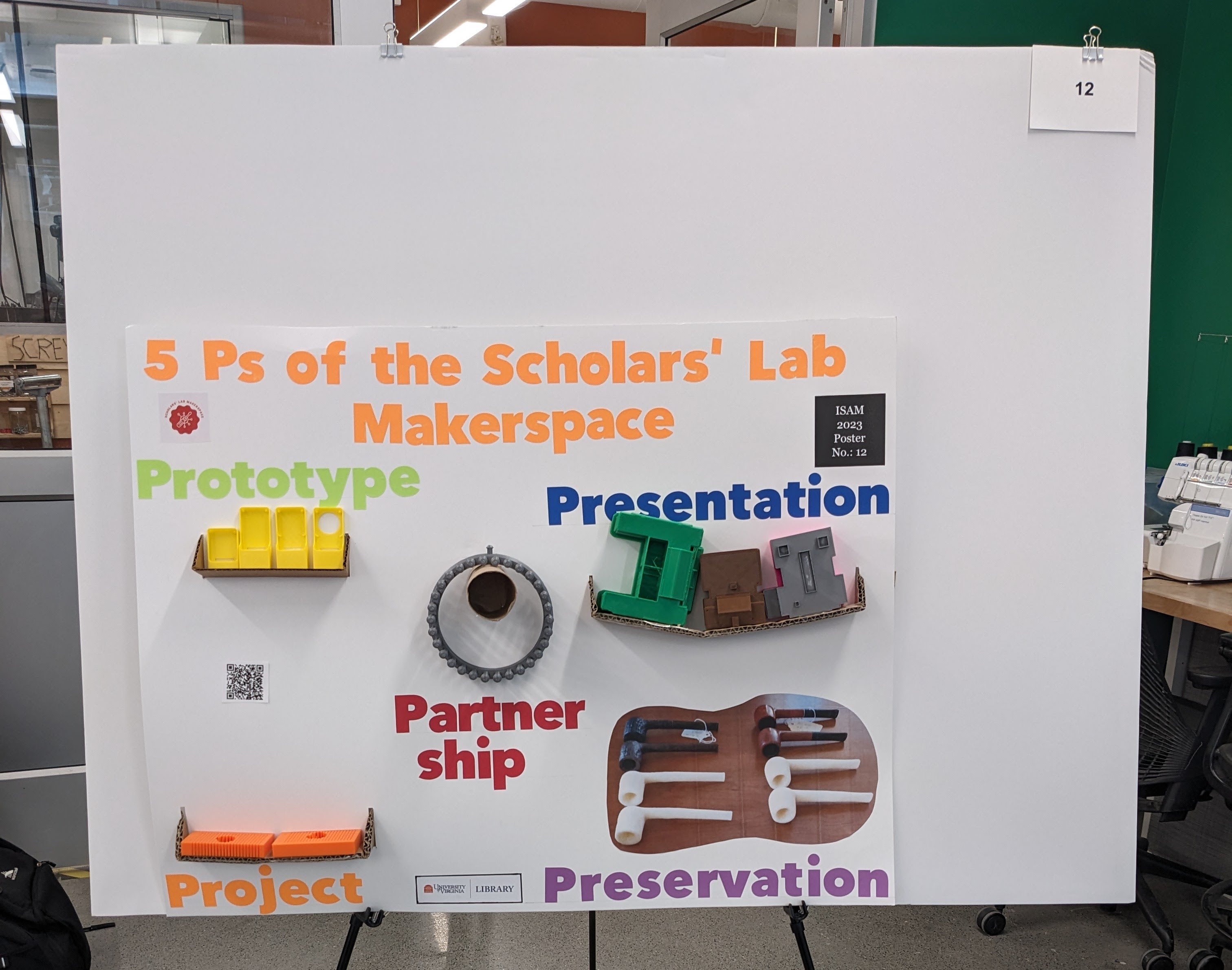

The 5 Ps of Library Makerspaces

Over the past 9 years of participating in and running a university library makerspace, I have found that our users do five things consistently. These are what I call the Five Ps of our Makerspace: Prototyping, Presentation, Preservation, Products, Partnerships. This poster shows the importance of each “P” and the unique position the Library plays in cultivating the five P’s of making at the University of Virginia. The Scholars’ Lab Makerspace began in 2014 as an extension of the existing Scholars’ Lab. Scholars’ Lab is the UVA Library’s community lab for the practice of experimental scholarship in all disciplines, informed by digital humanities, spatial technologies, and cultural heritage approaches.

We offer mentoring, collaboration, and a safe and supportive community experience for anyone curious about learning to push disciplinary and methodological boundaries through new approaches. We’re foremost a space for learning together—about anything—by experimenting. Think of us as friends and colleagues who can help you teach yourself new ways of approaching your interests [1].

The goal of creating a Makerspace in the Scholars’ Lab was to provide a space and the equipment to allow scholars (faculty, students, and staff) to experiment with new ways and methods of doing research. Some questions that birthed the makerspace were: What happens if an English professor has access to an Arduino? What if an MFA grad student could build a poem out of wood? How can a Music PhD student compose an interactive piece with a Raspberry Pi? What will students make with 3D printers, crafting supplies, electronics, button makers, and the space and freedom to create whatever they want?

After observing the results of scholars using the space and the equipment, five types of making came into view.

Prototyping:

“A prototype is a draft version of a product that allows you to explore your ideas and show the intention behind a feature or the overall design concept to users before investing time and money into development. A prototype can be anything from paper drawings (low-fidelity)” to something made of cardboard, or the same material as the final product (high-fidelity) [2].

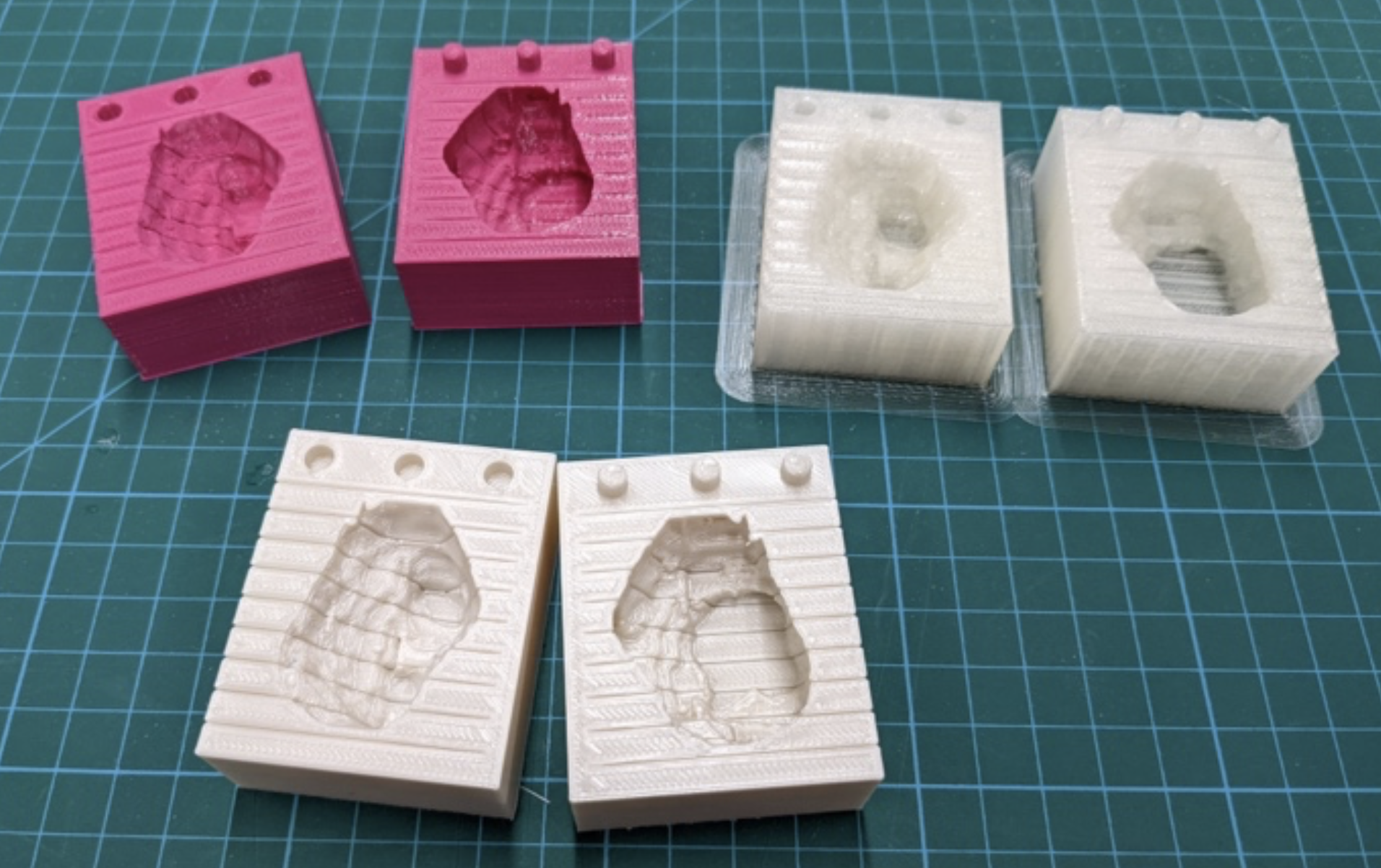

For example, two medical students needed a mold that would hold a woodchuck liver and allow them to slice it for tumor research. We made a 3D model of the tumor from CT scans then used Fusion 360 to create a slicer. After 3D printing, we were able to fine tune the dimensions of the slicer.

Figure 1: Multiple prototypes of a woodchuck liver slicer.

Figure 1: Multiple prototypes of a woodchuck liver slicer.

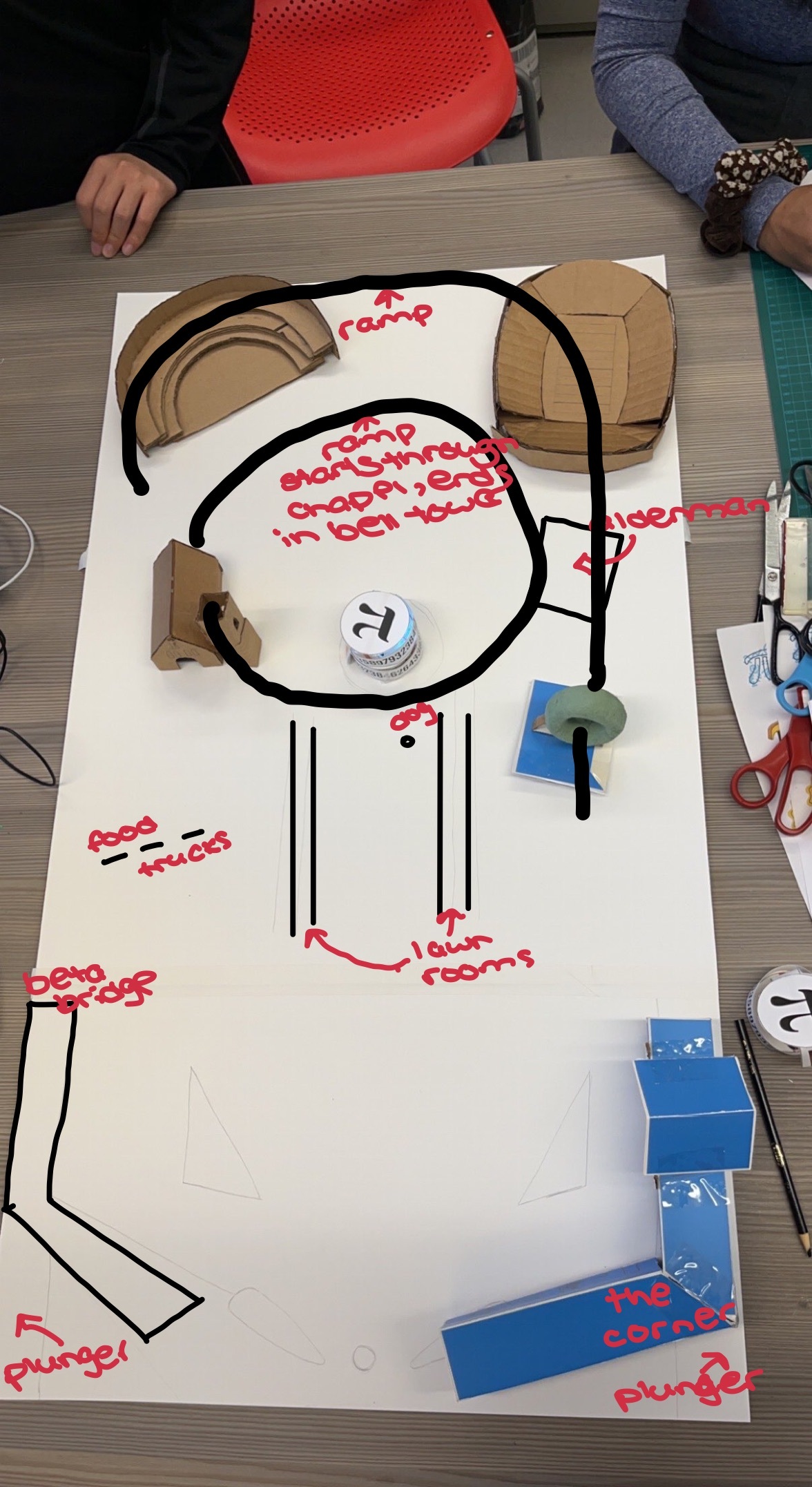

Recently, our student employees, who we call Makerspace Technologists, decided to make a pinball machine. We used paper and cardboard to prototype the playfield and obstacles of the pinball machine.

Figure 2: Layout of our pinball machine.

Figure 2: Layout of our pinball machine.

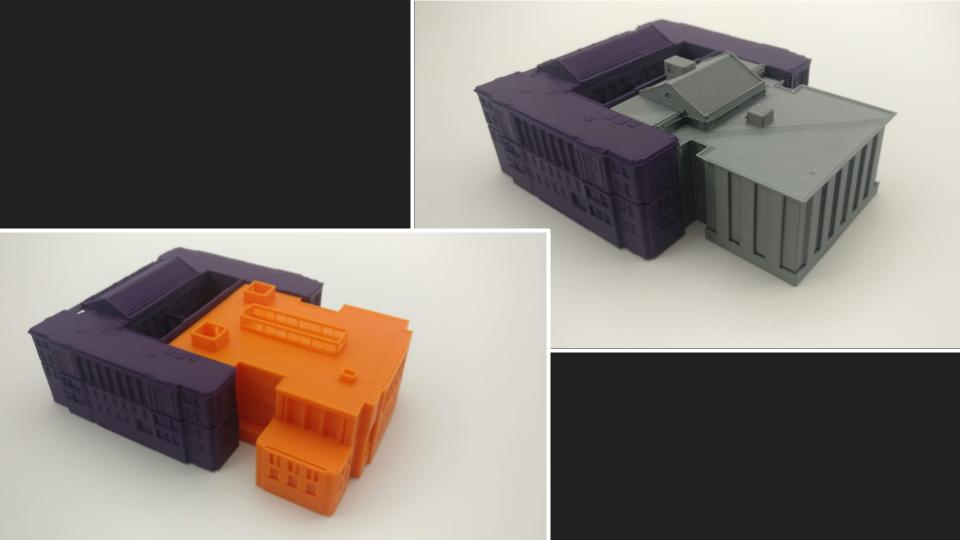

Presentation:

If a picture is worth a thousand words, then a three-dimensional object is worth a million words. 3D printing an object often provides unique and quick ways to present information. The main library at UVA is almost finished with some major renovations which include removing a large center building that… here, let me show you with this 3D model instead. In the picture below, the gray portion was demolished and rebuilt as seen in orange.

Figure 3: Before (grey) and after (orange) renovation.

Figure 3: Before (grey) and after (orange) renovation.

A 3D topographical map of the United States also shows the dramatic change in elevation of the Sierra Nevada and Rocky Mountain ranges. It’s no wonder that the Southwest US is so dry and arid. A physical representation of these weather barriers makes clear the reason why these areas are deserts.

Figure 4: CNC routed topographical map of the United States. Image source [3].

Figure 4: CNC routed topographical map of the United States. Image source [3].

Preservation:

All things must pass away/All things must pass/None of life’s strings can last [4]. But if you scan the object with a high-resolution 3D scanner, you can make a 3D model which can be reproduced with a 3D printer! In this way, the object can be preserved in some fashion. This is the cultural heritage and informatics approach at the Scholars’ Lab. As one example, the author William Faulkner was a writer-in-residence at UVA in 1958. UVA was gifted two of his smoking pipes. Held in the Library’s Special Collections, the pipes are inaccessible to the public. But making a 3D model of the objects, and 3D printing them allows the objects to be displayed to the public, and even allow the public to handle the objects.

Figure 5: Replicas of Faulkner’s smoking pipes.

Figure 5: Replicas of Faulkner’s smoking pipes.

If the copies are damaged, another can easily be made.

Products:

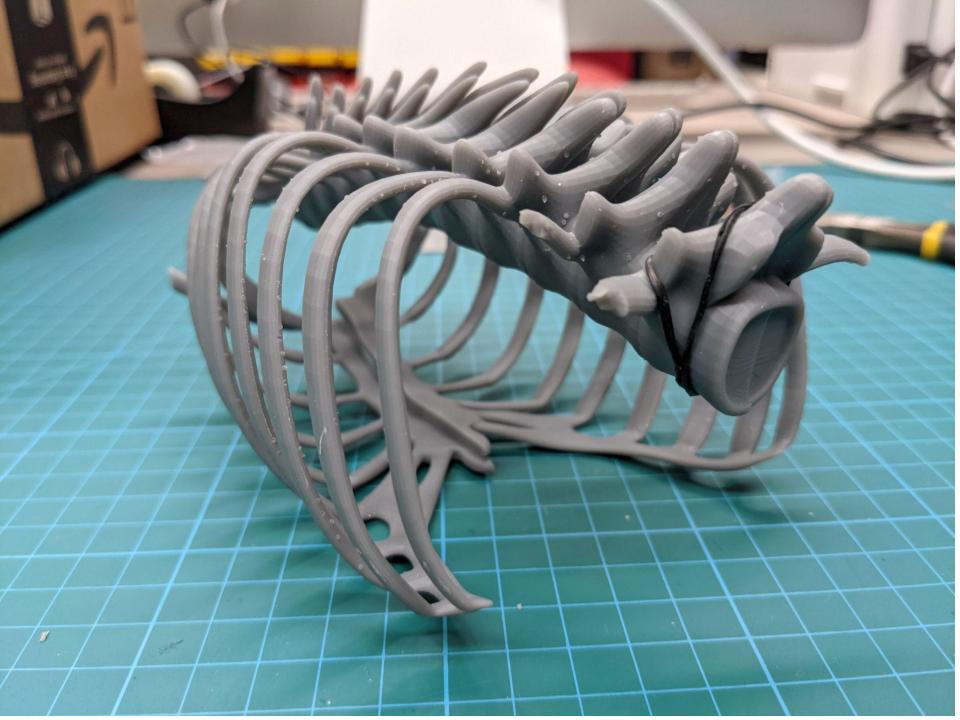

One of the main purposes of all the efforts in a makerspace is to make a product, the completed object of intended creation. One interesting product was 3D printing baby sized rib cages for medical students to train with. Previously, students used chicken rib cages. But 3D printed rib cages allow for much better representation of actual anatomy.

Figure 6: 3D printed baby sized rib cage.

Figure 6: 3D printed baby sized rib cage.

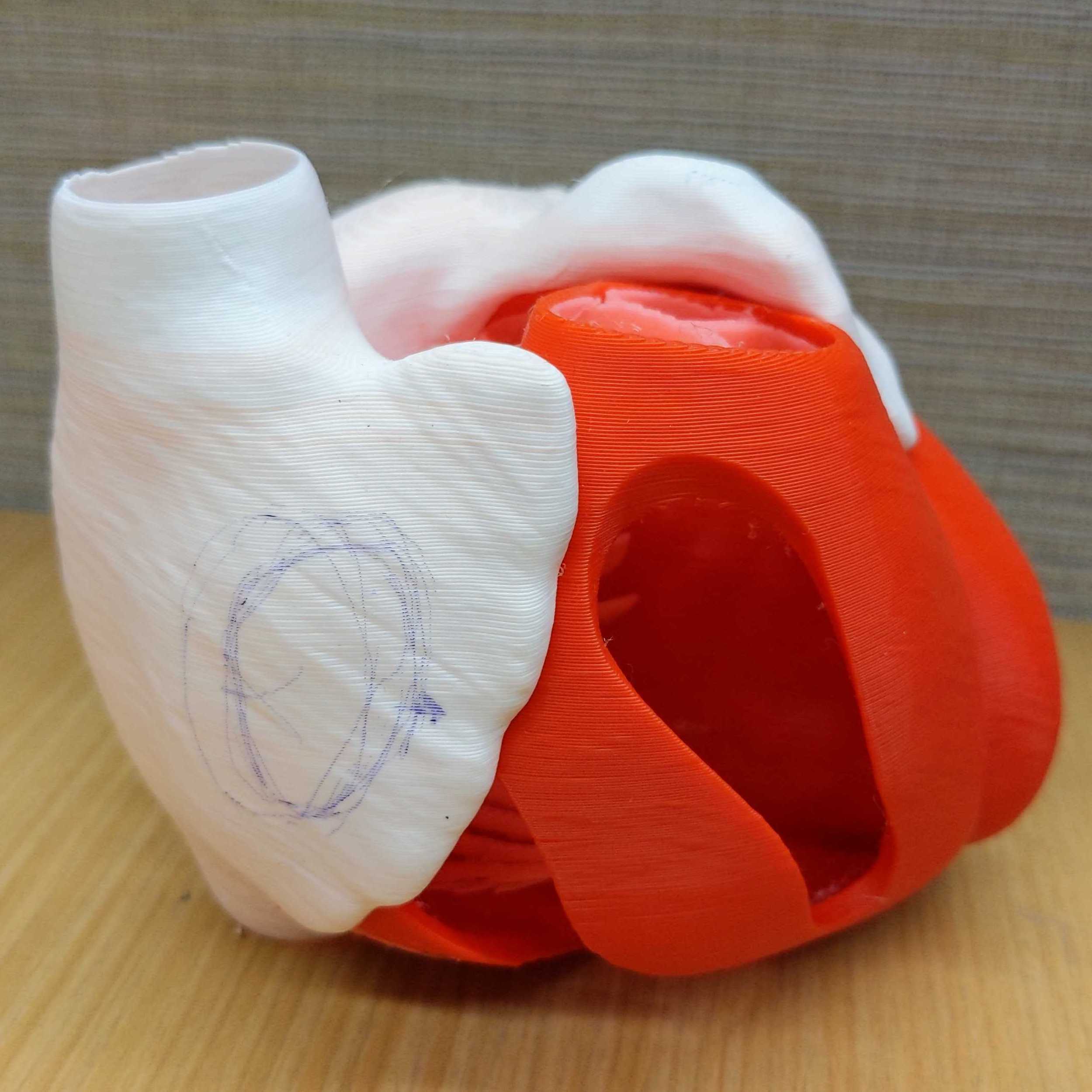

Additionally, this past summer, a medical doctor at UVA’s hospital requested 3D models of a heart so that he and his residents can practice catheter movements on the models. I found a satisfactory model of the heart online and printed an initial model. After reviewing the model, the doctor offered several tweaks to the model to make it fit their workflow.

Figure 7: First 3D printed heart model.

Figure 7: First 3D printed heart model.

I edited the model in Fusion 360, increasing hole sizes, adding new holes, and extending sections where arteries and veins would go. After a second round of review, the final heart models were printed.

Figure 8: Second 3D printed heart model with some revisions.

Figure 8: Second 3D printed heart model with some revisions.

Figure 9: Final version of the 3D printed heart model.

Figure 9: Final version of the 3D printed heart model.

Other finished products come from the many workshops designed and run by our student workers, who we call Makerspace Technologists. From totebags, stuffed buddies, jewelry from spoons and forks, stamps, book safes, stickers and many others, our Technologists provide workshops that get students making usable products.

Figure 10: Tote bags from the totebag workshop.

Figure 10: Tote bags from the totebag workshop.

Figure 11: Custom made stamps.

Figure 11: Custom made stamps.

Figure 11: Students make their own stuffed buddy.

Figure 11: Students make their own stuffed buddy.

Partnerships:

Arguably one of the most important aspects of a makerspace is creating connections, building networks, fostering collaboration. The Scholars’ Lab makerspace is a space where architects and engineers, medical students and gamers, musicians and historians have come to collaborate and build solutions and experiments. As shown in each of the previous four Ps, projects in the Makerspace usually involve collaboration with other groups from differing departments. Not all collaborations involve 3D printing, or even happen in the Makerspace. For several years, we collaborated with an Architecture professor to provide Arduinos and training on Arduinos for the course ARCH 5424 Direct Cinema Media Fabrics [5]. A co-worker and I recently worked with an Archeology professor to provide her class with the option to either create a VR representation or a 3D printed model of ancient Roman buildings [6]. Before the pandemic, a Library co-worker’s mother would knit hats for newborns at the UVA Hospital. She found that the looms she could purchase in the store created hats with holes too large to be effective for tiny newborn heads. A student employee worked with her to design and 3D print an appropriately sized loom for knitting the perfect baby hats [7]!

Figure 12: Custom designed baby hat knitting looms.

Figure 12: Custom designed baby hat knitting looms.

As a final example of collaboration, student employees hold at least two workshops each semester. Workshops are open to everyone at the University. Each workshop brings a mix of students from a variety of disciplines, from the hard sciences to social sciences to the humanities. This mixing of disciplines provides a great opportunity for scholars to share ideas across otherwise siloed school experiences. This unique mixing of disciplines led to collaboration between an English PhD student [8] and a Computer Science PhD student [9]. While both worked as Makerspace Technologists for the Scholars’ Lab, they combined interests in Humanities and technology to do research in robotics and humanities [10]. After discovering their combined interest in research, they also discovered interest in each other and eventually married! While not all makerspace collaborations lead to such unions, this example does show the inherent desire for all collaborations is the development and growth of mutually meaningful person-to-person relationships.

References

[1] “About,” Scholars’ Lab. https://scholarslab.lib.virginia.edu/about/ (accessed Sep. 30, 2023).

[2] “Prototyping - Usability.gov.” https://www.usability.gov/how-to-and-tools/methods/prototyping.html (accessed Aug. 30, 2023).

[3] “3D STL Model for CNC Router Engraver Carving Machine Relief - Etsy.” https://www.etsy.com/listing/906859077/3d-stl-model-for-cnc-router-engraver?utm_source=OpenGraph&utm_medium=PageTools&utm_campaign=Share (accessed Sep. 29, 2023).

[4] “All Things Must Pass (song),” Wikipedia. Mar. 14, 2023. Accessed: Aug. 30, 2023. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=All_Things_Must_Pass_(song)&oldid=1144612198

[5] “Arch 5424 Direct Cinema Media Fabrics.” https://web.arch.virginia.edu/arch5424/ (accessed Sep. 29, 2023).

[6] “You Will Never Think of Houses the Same Way,” Jul. 06, 2017. http://magazine.arts.virginia.edu/stories/you-will-never-think-of-houses-the-same-way (accessed Sep. 29, 2023).

[7] “Perfect – just what I wanted!,” Live & Learn!, Nov. 13, 2019. https://ruthk.net/2019/11/13/perfect-just-what-i-wanted/ (accessed Sep. 29, 2023).

[8] “Christian Howard-Sukhil.” https://choward345.github.io/ (accessed Sep. 30, 2023).

[9] V. Sukhil, “Varundev Sukhil.” https://varundevsukhil.github.io/ (accessed Sep. 30, 2023).

[10] Human Machines & Mechanical Humans - Christian Howard - TEDxCharlottesville, (Feb. 14, 2018). Accessed: Sep. 30, 2023. [Online Video]. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mbyURiWF0mw