Why do we trust automated tests?

I’m fascinated by this question. Really, it’s more of an academic problem than a practical one - as an engineering practice, testing just works, for lots of simple and well-understood reasons. Tests encourage modularity; the process of describing a problem with tests makes you understand it better; testing forces you to go beyond the “happy case” and consider edge cases; they provide a kind of functional documentation of the code, making it easier for other developers to get up to speed on what the program is supposed to do; and they inject a sort of refactoring spidey-sense into the codebase, a guard against regressions when features are added.

At the same time, though, there’s a kind of software-philosophical paradox at work. Test are just code - they’re made of the same stuff as the programs they evaluate. They’re highly specialized, meta-programs that operate on other programs, but programs nonetheless, and vulnerable to the same ailments that plague regular code. And yet we trust tests in a way that we don’t trust application code. When a test fails, we tend to believe that the application is broken, not the tests. Why, though? If the tests are fallible, then why don’t they need their own tests, which in turn would need their own, and so on and so forth? Isn’t it just like fighting fire with fire? If code is unreliable by definition, then there’s something strange about trying to conquer unreliability with more unreliability.

At first, I sort of papered over this question by imagining that there was some kind of deep, categorical difference between resting code and “regular” code. The tests/ directory was a magical realm, an alternative plane of engineering subject to a different rules. Tests were a boolean thing, present or absent, on or off - the only question I knew to ask was “Does it have tests?”, and, a correlate of that, “What’s the coverage level?” (ie, “How many tests does it have?”) The assumption being, of course, that the tests were automatically trustworthy just because they existed. This is false, of course [1]. The process of describing code with tests is just another programming problem, a game at which you constantly make mistakes - everything from simple errors in syntax and logic up to really subtle, hellish-to-track-down problems that grow out of design flaws in the testing harness. Just as it’s impossible to write any kind of non-trivial program that doesn’t have bugs, I’ve never written a test suite that didn’t (doesn’t) have false positives, false negatives, or “air guitar” assertions (which don’t fail, but somehow misunderstand the code, and fail to hook onto meaningful functionality).

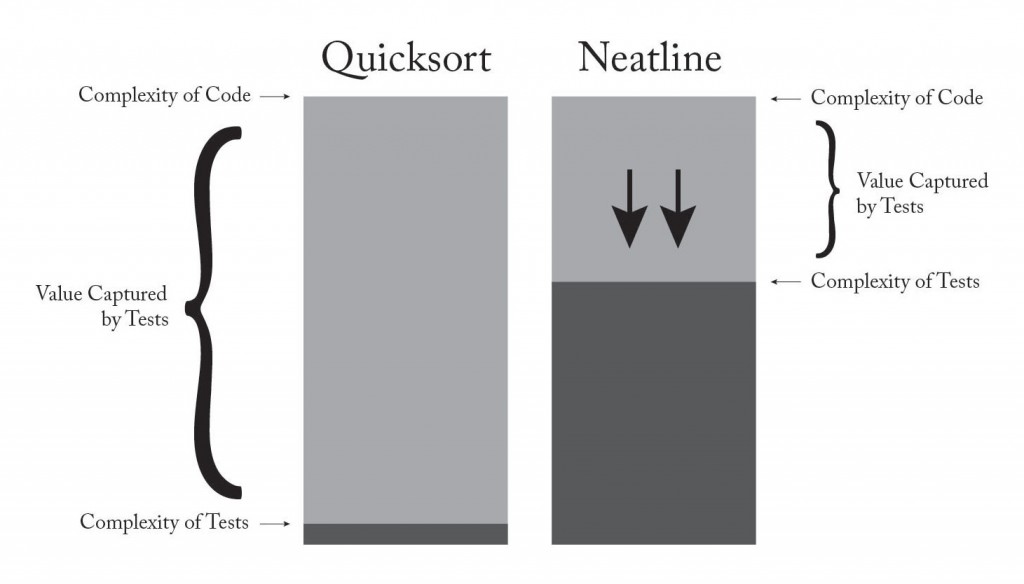

So, back to the drawing board - if there’s no secret sauce that makes tests more reliable in principle, where does their authority come from? In place of the category difference, I’ve started to think about it just in terms of a relative falloff in complexity between the application and the tests. Testing works, I think, simply because it’s generally easier to formalize what code should do than how it should do it. All else equal, tests are less likely to contain errors, so it makes more sense to assume that the tests are right and the application is wrong, and not the other way around. By this logic, the value added is proportional to the height of this “complexity cliff” between the application and the tests, the extent to which it’s easier to write the tests than to make them pass. I’ve starting using this as a heuristic for evaluating the practical value of a test: The most valuable tests are the ones that are trivially easy to write, and yet assert the functionality of code that is extremely complex; the least valuable are the ones that approach (or even surpass) the complexity of their subjects.

For example, take something like a sorting algorithm. The actual implementation could be rather dense (ignore that a custom quicksort in JavaScript is never useful):

The tests, though, can be fantastically simple:

These are ideal tests. They completely describe the functionality of the code, and yet they fall out of your fingers effortlessly. A mistake here would be glaringly obvious, and thus extremely unlikely - a failure in the suite almost certainly means that the code is actually defective, not that it’s being exercised incorrectly by the tests.

Of course, this is a cherry-picked example. Sorting algorithms are inherently easy to test - the complexity gap opens up almost automatically, with little effort on the part of the programmer. Usually, of course, this isn’t the case - testing can be fiendishly difficult, especially when you’re working with stateful programs that don’t have the nice, data-in-data-out symmetry of a single function. For example, think about thick JavaScript applications in the browser. A huge amount of busywork has to happen before you can start writing actual tests - HTML fixtures have to be generated and plugged into the testing environment; AJAX calls have to be intercepted by a mock server; and since the entire test suite runs inside a single, shared global environment (PhantomJS, a browser), the application has to be manually burned down and reset to a default state before each test.

In the real world, tests are never this easy - the “complexity cliff” will almost always be smaller, the tests less authoritative. But I’ve found that this way of thinking about tests - as code that has an imperative to be simpler than the application - provides a kind of second axis along which to apply effort when writing tests. Instead of just writing more tests, I’ve started spending a lot more time working on low-level, infrastructural improvements to the testing harness, the set of abstract building blocks out of which the tests are constructed. So far, this has taken the form of building up semantic abstractions around the test suite, collections of helpers and high-level assertions that can be composed together to tell stories about the code. After a while, you end up with a kind of codebase-specific DSL that lets you assert functionality at a really high, almost conversational level. The chaotic stage-setting work fades away, leaving just the rationale, the narrative, the meaning of the tests.

It becomes an optimization problem - instead of just trying to make the tests wider (higher coverage), I’ve also started trying to make the tests lower, to drive down complexity as far towards the quicksort-like tests as possible. It’s sort of like trying to boost the “profit margin” of the tests - more value is captured as the difficulty of the tests dips further and further below the difficulty of the application:

[1] Dangerously false, perhaps, since it basically gives you free license to to write careless, kludgy tests - if a good test is a test that exists, then why bother putting in the extra effort to make it concise, semantic, readable?