If you are a fan of D&D, you know that there are countless different shapes, colors, and sizes of dice out there. Honestly, it can be a bit overwhelming for a beginner looking to buy their first set. This was my experience when I first learned to play D&D (virtually) with a group of friends during the Pandemic, and I became interested in learning the history of these little objects. Perhaps surprisingly, I discovered that cultures across the globe and across time have developed their own versions of dice. The ancient Greeks and Romans were no exception. So-called knucklebones (or astragaloi in ancient Greek and tali in Latin) refer to dice that were used by the ancient Greeks and Romans to play a variety of different games. Originally the anklebones of sheep and goats, knucklebones could also be made from metal, stone, glass, and terracotta, like the eight glass knucklebones from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Group of eight knucklebones, 3rd-2nd century BCE, glass, Greece, Metropolitan Museum of Art 1992.266.3-.10.

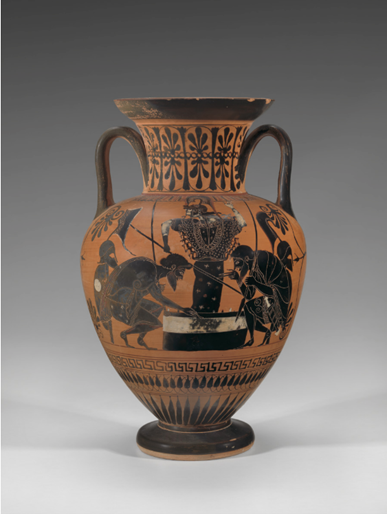

There are numerous games that could be played by both children and adults. For children, a simple game akin to jacks was common. The most popular game for adults was much more complex, similar to Yahtzee today. For this game, each of side of a knucklebone (there are four long sides and three short sides) was assigned a different numerical value and then thrown in sets of four or five 35 times on a table. The person who rolled the highest score would win. The game is frequently depicted in art on ancient Greek vases, the most famous of which shows the Greek hero Achilles and warrior Ajax playing while taking a break during the Trojan War (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Achilles and Ajax playing a dice game, black-figure neck amphora, attributed to the Leagros Group, ca. 510 BCE, terracotta, Athens, Greece. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts 60.10.

Interestingly, this game could also have an oracular function, especially for unmarried young women. When throwing a set of four or five dice, the combination of the top-facing sides of each knucklebone would have different names and meanings associated with them. For example, “Aphrodite’s throw” was a perfect throw, in which the knucklebones all land on different sides and was interpreted to mean success for a young bride in marriage and motherhood. Archaeologists find knucklebones all over the Mediterranean, but especially at sanctuaries. Over 22,000 knucklebones were found at the Corycian Cave, which is primarily a Sanctuary of the Nymphs, and is located on the slopes of Mt. Parnassos near the famous Sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi, where the Delphic Oracle gave prophecies to religious pilgrims. The Nymphs, who are female nature divinities, were also the guardians of young women, particularly during the undoubtedly anxious time as they transition into married life. These young women would bring gifts, such as vases, relief carvings, and knucklebones, as dedications to the Nymphs at their sanctuaries, which were usually at caves (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Dedicatory relief carving of a cave, depicting (from L-R) Acheloos (part bull/human father of the Nymphs), Pan playing his panpipes (part goat/human god of shepherding and acquaintance of the Nymphs), and three Nymphs, ca. 300 BCE, marble, from the Sanctuary of the Nymphs and Pan at Vari Cave near Athens, Greece. National Archaeological Museum in Athens.

As a Ph.D. Candidate in the Program for Mediterranean Art and Archaeology in the Art Department here at UVa (supervised by Dr. Tyler Jo Smith), I am currently working on my dissertation that focuses on caves used as places of worship in and around Athens ca. 750-300 BCE, the height of ancient Greece as we know it. So, when Dr. Andrej Petrovic (Professor of Classics) told me that the Department of Classics had long-ago inherited an incomplete set of three knucklebones used for teaching, I knew that I had to take the opportunity as a Praxis Fellow in the Digital Humanities to 3D print the missing di.

First, with one-on-one guidance of Victoria Valdez (Assistant Director of the Visual Resources Collection), I made a digital model of one knucklebone using photogrammetry, which is the process of using photographs to recreate an object or space as a digital 3D model. Surprisingly, the model only took about an hour to complete. It is very easy to render digital models in 3D these days, using various computer software (e.g., Agisoft Metashape) or apps for phones or tablets (e.g., Polycam). Photogrammetry requires a lot of photographs to create a detailed model, so we took about 70 photographs of one of the knucklebones outside in diffuse natural sunlight. This process included taking 35 or so photographs of the top-side of the bone from different angles and then flipping it over with the bottom-side up to take the rest of the pictures. Next, we uploaded the photographs to a Agisoft Metashape to create separate 3D models of the top and bottom views. We were able to stitch together the top and bottom views and perfect the shape of the complete model using Autodesk Mesh Mixer. Finally, we were ready to print. We added some structural supports that are needed for the printing process, saved the model as an STL file, and digitally sent it to the printer. The Visual Resources Collection has a Form2 resin printer that took 4 hours and 30 minutes to create the product (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. The 3D printed knucklebone with structural supports next to the original.

Once finished, we removed the structural supports and did a light sanding to smooth any rough edges. Then, walah! The new bone was finished (see Figure 5). I was surprised how smooth the final product was and how the weight felt similar to the actual bone.

Figure 5. The finished 3D printed knucklebone and the original.

My project is not complete though. Next, with the guidance of Ammon Shepherd (Makerspace Manager and Lead Research Technologist), I want to play around using different printers and plastics in the Scholar’s Lab Makerspaces, create customized, embossed decorations, and experiment with sanding tools and paints to create lifelike textures and colors. So, stay tuned!