Toward the beginning of the semester, I was contacted by Brandon Walsh, a UVA alumnus and the current Mellon Digital Humanities Fellow at Washington and Lee. As part of his fellowship, Brandon has been pairing UVA DH folks with professors at Washington and Lee; the initiative is aimed at integrating new developments in technology with more traditional pedagogical methods practiced at a liberal arts university (read more about it here: http://augustafreepress.com/mellon-foundation-grants-washington-and-lee-funds-for-digital-humanities-study-of-histor/). Brandon paired me with Professor Taylor Walle, who is teaching Washington and Lee’s English 232: “Frantic and Sickly, Idle and Extravagant: The Gothic Novel, 1764-2002.”

Now I’m no expert in the gothic novel, but after talking with Taylor, it became clear that our interests overlapped in unexpected yet productive ways. That is, one of Taylor’s aims in her course is to trouble the distinction between “highbrow” and “lowbrow” literature. A few of the questions that Taylor set to her students include: “Do you think the gothic deserves its long history of being associated with ‘popular’ (read: trash) fiction? Do you think the distinction between ‘highbrow’ and ‘lowbrow’ is legitimate or useful? How do we determine what counts as ‘high’ and what counts as ‘low’? Are these categories meaningful or arbitrary?” These questions resonated with my own research into what Nick Levey has termed “post-press” literature (http://post45.research.yale.edu/2016/02/post-press-literature-self-published-authors-in-the-literary-field-3/) and other technologically experimental publication platforms, including Twitter and digital comics. Because such self-published literature is not approved by the “gatekeepers” of the publishing market, many people – especially authors who have successfully navigated the publishing market – have denigrated self-published literature. Award-winning author Laurie Gough, for instance, states: “I’d rather share a cabin on a Disney cruise with Donald Trump than self-publish. To get a book published in the traditional way, and for people to actually respect it and want to read it — you have to go through the gatekeepers of agents, publishers, editors, national and international reviewers. These gatekeepers are assessing whether or not your work is any good. …The problem with self-publishing is that it requires zero gatekeepers.” So we can see a current-day example of the tension between so-called “highbrow” and “lowbrow” literature in the form of traditionally-published vs. independent and experimental publication methods.

I started looking for post-press and technologically-experimental literature that echoes gothic themes and characteristics. One work that Taylor and her class were discussing particularly caught my interest, namely, Oscar Wilde’s Picture of Dorian Gray. So I began my search for the “digital gothic” using this work as my focal point, and the results were intriguing. Not only has Dorian Gray been a favorite subject of Hollywood, but there have also been multiple graphic novels starring Dorian. Bluewater Comics even published an interactive, digital comic titled Dorian Gray that incorporates sound and movement.

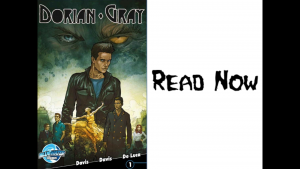

Screen shot of Dorian Gray the digital comic, created by Darren G. Davis, Scott Davis, and Federico De Luca.

I continued brainstorming and gathering materials, until it was finally time to visit Taylor’s class on Wednesday, March 1, 2017. Despite the relatively early hour (8:30 am), Taylor’s class was enthusiastic and eager to participate. We reviewed the categories of highbrow and lowbrow literature before jumping into a discussion about Wilde’s Dorian Gray, which the students had just finished reading. Wilde’s descriptions and imagery gave us a pivoting point to examine other interpretations of Wilde’s work, particularly these graphic versions. But before we looked at these versions, I had the students watch part of Scott McCloud’s TED Talk, “The Visual Magic of Comics” (https://www.ted.com/talks/scott_mccloud_on_comics). McCloud clearly and persuasively lays out the visual resources available to comics, and he further discusses the future of comics in a digital age. Armed with the vocabulary outlined by McCloud, we examined first a (printed) graphic novel and then the digital comic version of Wilde’s novel.

Our examination of the visual affordances of graphic novels and digital comics

We looked at several other instances of contemporary gothic digital literature, including webcomics (particularly “Bongcheon-Dong Ghost”) and hypertext fiction (Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl, a retelling of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein featuring the creation of a female monster).

Students examine Shelley Jackson’s hypertext fiction, Patchwork Girl

The students were particularly interested in the interactivity and changing role of the reader/user demanded by digital literature. One student observed that the physical reactions to print literature and interactive digital literature are different in that interactivity heightens the physical response, especially during moments of shock or horror (if you want to experience this yourself, check out the webcomic “Bongcheon-Dong Ghost” - http://comic.naver.com/webtoon/detail.nhn?titleId=350217&no=31&weekday=tue). Another student speculated that it might be precisely because of these visceral reactions that such digital literature is relegated to “horror” or “popular” genres rather than being considered “serious” literature.

After the class was over, Taylor expressed her enthusiasm for the material and medial considerations that this foray into the digital had on her class. I know I certainly enjoyed the lively and insightful conversation that emerged from this unlikely pairing of the gothic and the digital, and I am excited to think more about the developing and emerging genres inspired by these new literary forms!