As promised in my previous post, here is an idea for this year’s Praxis Program. It is uncertain at this early stage of brainstorming whether it will be retained as the one uniting everybody’s creative forces and ingenuity, but I believe it has a lot of potential of unfolding into a project where everybody’s common interests meet: library’s holdings, global culture and world languages, power and inequality, literature and sound. At its core, it is as humanistic as it can be, and its execution requires the use of common digital humanities and critical making techniques, that we are here to train for. But before I get to the idea, let me take you to a journey where books are no longer written, nor pressed into rectangular objets made out of ink and paper and they are by no means meant to be read.

The end of books

More than a hundred years ago, at the turn of the 19th century, Octave Uzanne, a French bibliophile and journalist, conceived The End of Books1 (audio file) in one of his most cited short nonfictional works. His prediction, mid way between pure speculation and prophecy was that the new media of his time, the rise of electricity and phonography, would soon replace the old Gutenberg’s invention.

“I do not believe (and the progress of electricity and modern mechanism forbids me to believe) that Gutenberg’s invention can do otherwise than sooner or later fall into desuetude as a means of current interpretation of our mental products.”

“our grand-children will no longer trust their works to this somewhat antiquated process, now become very easy to replace by phonography”.

The leap was enormous. Uzanne’s reverie, not only depicted books as a dying medium with no future, but shifted their inherent mutism to the vivacity of the audio recording. It is important to notice, and Uzanne himself insists on the matter, that books don’t have to put a strain on our eyes and bodies anymore, keeping us immobile, squint and hunched over the small print of the page.

“You will surely agree with me that reading, as we practice it today, soon brings on great weariness; for not only does it require of the brain a sustained attention which consumes a large proportion of the cerebral phosphates, but it also forces our bodies into various fatiguing attitudes.”

“Our eyes (…) have been too long abused, and I like to fancy that some one will soon discover the need there is that they should be relieved by laying a greater burden upon our ears.”

What is in the book that can not live in another recorded medium? Ideas, scientific knowledge and scholarship, literary work, can all exist in an audible format. For Uzanne, phonography not only can afford the contents of the book, but this change of reception through another sensory organ, the ear instead of the eye, has clear benefits for the overall mental and physical health of the listener.

“Hearers will not regret the time when they were readers; with eyes unwearied, with countenances refreshed, their air of careless freedom will witness to the benefits of the contemplative life.”

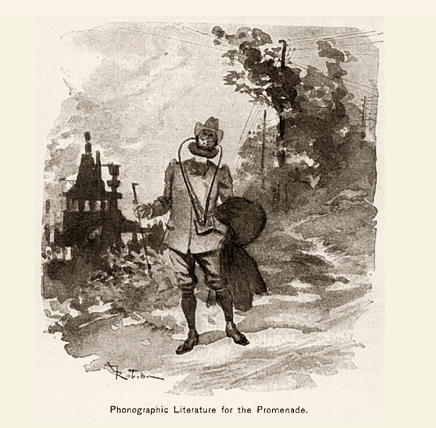

“At home, walking, sightseeing, these fortunate hearers will experience the ineffable delight of reconciling hygiene with instruction; of nourishing their minds while exercising their muscles for there will be pocket phono-operagraphs, for use during excursions among Alpine mountains or in the canyons of the Colorado.”

It is obvious that Uzanne not only imagined the audiobook but also a prototype portable device that would play it back.

It is worth noticing then, that before Sony’s Walkman, or Apple’s iPod “a pocket apparatus (…) suspended by a strap from the shoulder” was not designed to accommodate “a thousand songs in your pocket” (Steve Jobs) but a portable device to liberate the bibliophile’s body from the immobility of the study room.

Uzanne’s intuitions, albeit prophetic for the most part, failed to envision a future where both printed and audiobooks exist without posing a threat to each other. New technologies first thought as replacement to the old ones end up coexist offering alternative options of engagement. Audiobooks didn’t replace print books and certainly listening didn’t replace reading.

The impossible task of reading

However, reading, despite being an unhealthy activity as we just saw, heavily taxing one’s eyes and body, forcing its muscles to atrophy, is an overall impossible task. Too much to read, too little time.

“When Brandon was entering graduate school, an older student once summed up one of life’s problems as a sort of equation:

There is an infinite of material that one could read.

There is a finite amount of time that you can spend reading.

The lesson was that there are limits to the amount of material that even the most voracious reader can take in. One’s eyes can only move so quickly, one’s mind only process so much. This might sound depressing, as if you’re playing a losing game. But it can also be freeing: if you cannot read everything, why feel the need to try to do so? Instead, read what you can with care.”2

The sentiment is not new. Today’s readers may feel completely crushed under the weight and the abundance of reading material, but so did the erudite from the early modern era. Compiling methods (common place books, anthologies, florilegia) were thus put in place to compress books within books and save the reader from the folly of having to read everything in extenso.

Pierre Bayard in his first chapter of his now classic How to Talk About Books You Haven’t Read 3 addresses the issue by suggesting a few methods of non-reading.

“Reading is first and foremost non-reading. Even in the case of the most passionate lifelong readers, the act of picking up and opening a book masks the countergesture that occurs at the same time: the involuntary act of not picking up and not opening all the other books in the universe.” 4

The paradoxical nature of reading as non-reading, leads Bayard to an important insight: the contents of the book don’t really matter. They can be interchangeable even.5 After all, one’s memory of the books read, will inevitably boil its intricate details to a mush.

“ The interior of the book is less important than its exterior, or, if you prefer, the interior of the book is its exterior, since what counts in a book is the books alongside it.” 6

Don’t lose the forest for the trees is what Bayard basically saying. A library is a whole ecosystem that invites the “truly cultured to tend toward exhaustiveness rather than the accumulation of isolated bits of knowledge.”7 There is a whole network of connections between one book and the totality of books which is undermined when the attention is only given to each book’s singularities.

“It is, then, hardly important if a cultivated person hasn’t read a given book, for though he has no exact knowledge of its content, he may still know its location, or in other words how it is situated in relation to other books.”8

This “topographical approach” that values location over content, or content as location, and the nature of connections that one book enjoys with others is what Bayard calls collective library. Books are in dialogue with each other and the way to get even a faint echo of their conversations is movement. Moving around the library is preferable to the stasis over one particular location-book. The invention of hypertext as “an ongoing system of interconnecting documents” (Ted Nelson) was an attempt to establish the dynamic of movement to what had long seen as a static material. Only, one, still has to read…

The problem with languages.

Books are not only innumerable, there are also written in different languages, which is another reason inhibiting from reading them (all).

Before I move on, I would like to share with you a 1m07” clip from a recent episode of Twin Peaks The Return. In this scene special FBI Agent Gordon Cole, (played by David Lynch himself) after sending off his date (a French woman) to the bar, turns to his colleague Albert with a joke…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BemdreTqBA0

Lynch leaves the question linger in silence. It is a way to acknowledge the alarm that just went off: over six thousands languages!9 Despite their exact number, languages exist, people who speak them exist, and their world views and perspectives are as worthwhile as any. Languages are not a property of any particular population living on a specific location, they spill over borders, they travel like wild fire. But they are also used as means of oppression, when powerful cultural systems impose their monolingualism and consequently their world view to others. What does that make of the idea of the collective library? Who’s part of the collective and who’s not? How far can this collective be stretched to be a really inclusive collective and not just a club for the happy few?

It seems to me that World Languages are the blind spot in the discussions about global culture and diversity, about inequalities and web accessibility. Who gets the joke when it’s a word play intended to the speakers of the same language? Indeed, nobody laughs.

Listen, with all your ears, listen!

After this rather long detour, I am finally arriving to my proposal. I think it is time to consider Uzanne’s sensorial shift from the eye to the ear and pair it with Bayard’s dialogical relations of books in the collective library. Technically speaking this coupling would take the form of an exploratory device (or app). Its user would then be able to explore the stacks, through a bibliophilic auditory flânerie. Following a fortuitous trajectory inside the library10, the user will not only experience the books coming to life, but also the vast range of world languages in which these books are written11. As the user moves from one section of world literature to another, preinstalled sensors would capture her movement and send new content to her device, interfering with, or completely altering her soundscape. But, it is preferable not to discuss such technical details extensively, without a working prototype at hand.

Finally, the purpose of such a device, as mentioned before, is to offer a new experience of exploring the library other than having to look for a specific book, related to a specific topic often suggested by some course syllabus. I want to believe that a university library has much more to offer than a business-like exchange model. Despite not having an immediate benefit for the user, such a serendipitous bibliophilic auditory flânerie through a vast range of world languages may function as catalyst for awakening the desire to learn a new language.12 And when the user decides to stop her flânerie she will receive a prompt asking her if she wants to borrow a book, most likely one of which she has never heard before.

-

Octave Uzanne, The End of Books, consulté le 21 septembre 2017, https://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/u/uzanne/octave/end/. ↩

-

« Distant Reading », Introduction to Text Analysis, consulté le 15 septembre 2017, https://walshbr.com/textanalysiscoursebook/book/reading-at-scale/distant-reading/. ↩

-

Pierre Bayard, How to talk about books you haven’t read (New York, NY: Bloomsbury USA, 2007). ↩

-

Ibid. 17 ↩

-

Pierre Bayard, Et si les oeuvres changeaient d’auteur ? (Paris: Les Editions de Minuit, 2010). ↩

-

Bayard, How to talk about books you haven’t read., 30 ↩

-

Ibid., 27 ↩

-

Ibid., 30 ↩

-

A more comprehensive view on the languages spoken today in the world is offered by Ethnologue: « How many languages are there in the world? », Ethnologue, 3 mai 2016, https://www.ethnologue.com/guides/how-many-languages. ↩

-

The extent of fortuity can also be configured with a set of questions, allowing the user to add her parameters to the game. ↩

-

For prototyping purposes public domain librivox recordings will be used. ↩

-

I happen to fall in love with French from something I heard on the radio. ↩