Here Kelli describes her work with Professor Holly Pickett’s English 380 course at Washington & Lee. This work is supported by ASC grant expanding collaboration between Washington & Lee and the Scholars’ Lab.

“Playwrights write plays for the stage, not the study,” or so Roland Broude reminds us. Yet in my field of English literature, it’s quite common to study a play primarily as a textual object rather than a performance whose final form, tone, and affect all rely on extra-textual features. We don’t typically account for changes in play’s text during its first rehearsals (often these changes are implemented after the play text has been sent to print!), refinements in timing and intonation that occur during a show’s run, or even accidental line drops, forgotten words, or ad libs contrived by actors in reaction to something that happened during a particular performance. The reality of theater is that plays are constantly rewritten in a multitude of ways and we don’t have a lot of good ways to talk about that beyond acknowledgement.

In our world of the single-author study and the copyright, one of the consequences of seeing dramatic texts primarily as “literature” is the following assumption that the play is entirely the property of its author, who, as Broude argues, “exercises over it a droît moral: his is the sole right to establish the text, and, once it has been established, to alter it.” Teaching from this paradigm limits engagement with the performer or designer’s role in creating the play’s affect or meaning.

My work as a teacher, researcher, and theater director is to employ the digital humanities to help create ways that empower students to see a play as a complex nexus of decisions rather than a static textual object (for even the text itself is not stable). The problem that quickly surfaces is that performance (in many of its forms) is actually rather tricky to write about, because while we may have access to many versions and editions of the textual object (script), each enactment of that script is essentially ephemeral—a portion of it remains unrecoupable.

Peggy Phelan has claimed that the ontology of performance is essentially its irreproducibility and she acknowledges the difficulty this presents in analyzing performance art. We can try to fix parts of performance in a variety of non-performative forms such as narrative, photograph, or video recording, but those other media can only offer ekphrasis, not full reproduction. The ephemerality of performance gives it much of its affective weight and political potential. While we may not be able to entirely recapture performance outside of ekphrasis, my hope is that we can develop tools and methods for examining dramatic texts and performances that can help us to translate some of the harder-to-capture elements of performance into forms on which we can engage in various kinds of analysis or reflection. One of the questions I am currently thinking through is how can we “read” movement?

There’s some interesting work from the dance world that begins to think through these issues. Choreographer William Forsythe’s work with the Ohio State University (called Synchronous Objects) is particularly fascinating. Earlier work by choreographers such Rudolf Laban developed notational systems for dancers based on certain ideas about the body in space (Labanotation, for example). But I’ve been struggling to try to find a way that connects movement and text (like a script) in a meaningful way. How do certain textual features invite us to think about certain movements? What in the text tells us to move to a particular place or in a particular way? Asking students these questions is also a way of approaching the critical practices like the close reading and formal analysis which still remains important to much (but not all!) of our work in literary studies.

As a way to experiment with the relationship between movement and language, I worked with Holly Pickett’s English 380 class on two activities to help us discuss the relationship between the text and blocking of a scene. (Blocking is both a noun and a verb: it describes both the pattern of movement in a given scene and the act of directing/designing those movement patterns in rehearsal). First, I gave them the “to be or not to be” monologue from Hamlet Act 3, scene 1. I selected this text because I thought it was one they may be marginally familiar with and one that doesn’t contain many stage directions within the language (for example, when a character says “come here,” cuing another actor’s movement).

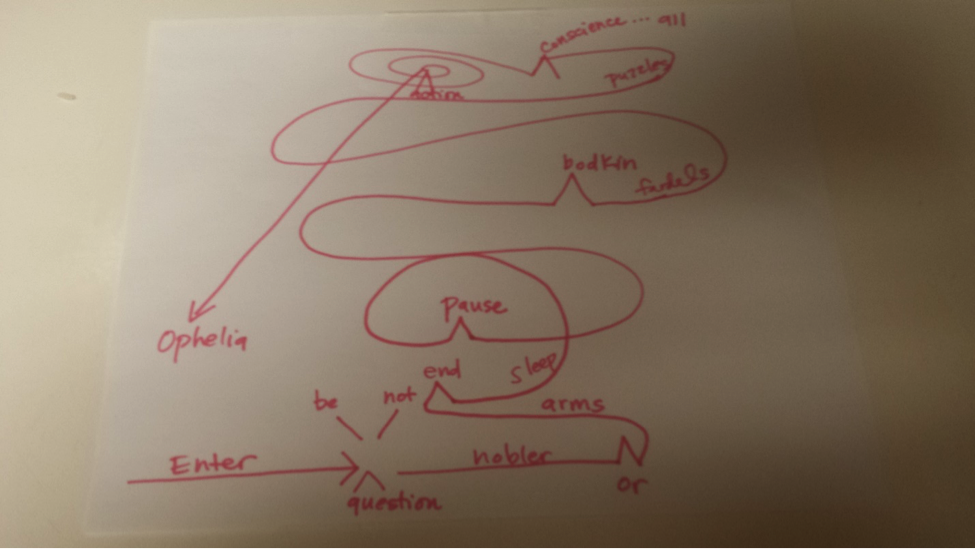

I instructed them to draw Hamlet’s path throughout the monologue—where does he start, end, and where does he move throughout the speech? I did not give them any instructions on how to notate pauses, changing positions or how long Hamlet took to walk somewhere as I was interested in seeing how they would choose to notate this.

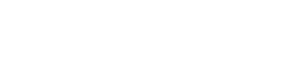

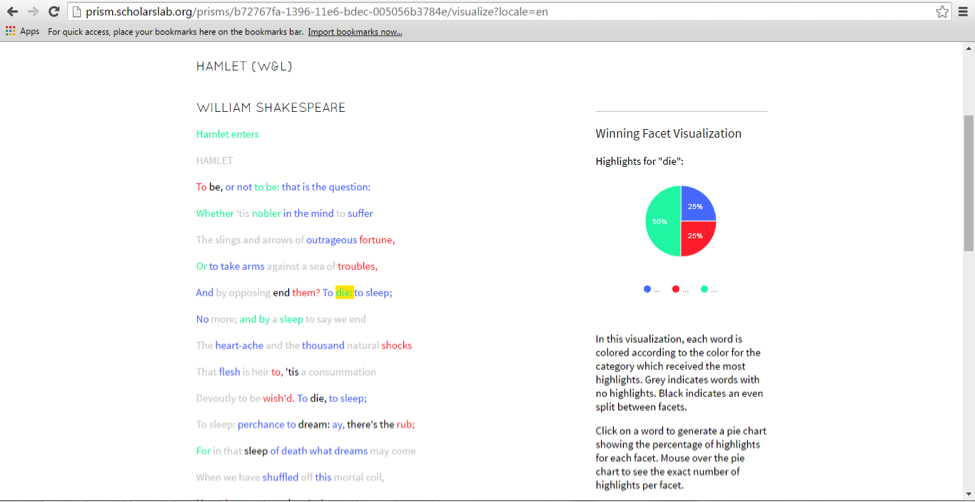

I also asked them to use Prism to mark up the monologue, indicating where Hamlet started moving, stopped moving, or changed position in their blocking. I did not tell them in which order to do these tasks just that they had to do both of them. At the end of the allotted 20 minutes, I taped all of the drawings on the board and pressed the visualization button on Prism to see what we found. The Prism results revealed that there was a great variety in blocking styles, yet there were definable loci of energy around certain parts of the text. (Here’s the full visualization)

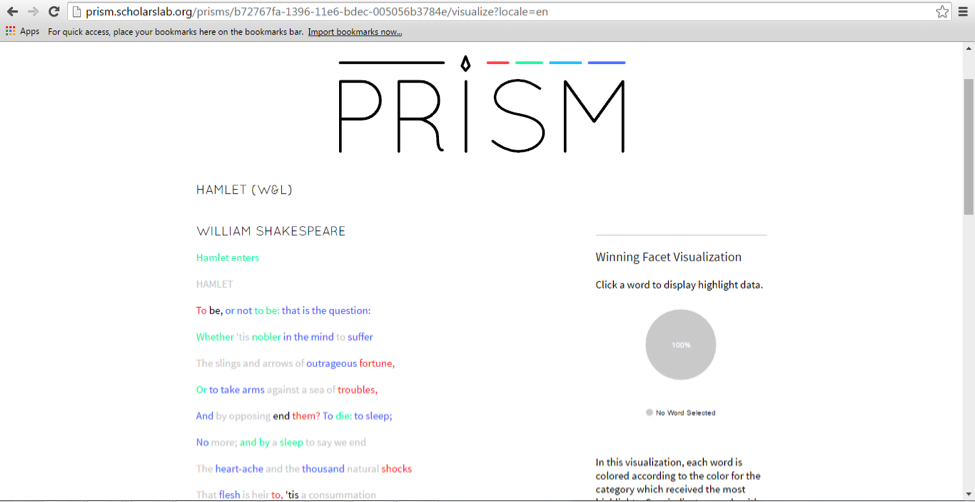

In this first image, you can see that a lot of students notated something around “end them? To die; to sleep,” but there disagreement as to what Hamlet was doing at those moments.

We zeroed in on the word “end” as Prism showed there was some debate as to what movement happened on that word. The Prism showed that students either had Hamlet change position without changing location (indicated by the blue) or stop moving all together (indicated by the red). No one had Hamlet begin moving on this word (which would have been indicated by green).

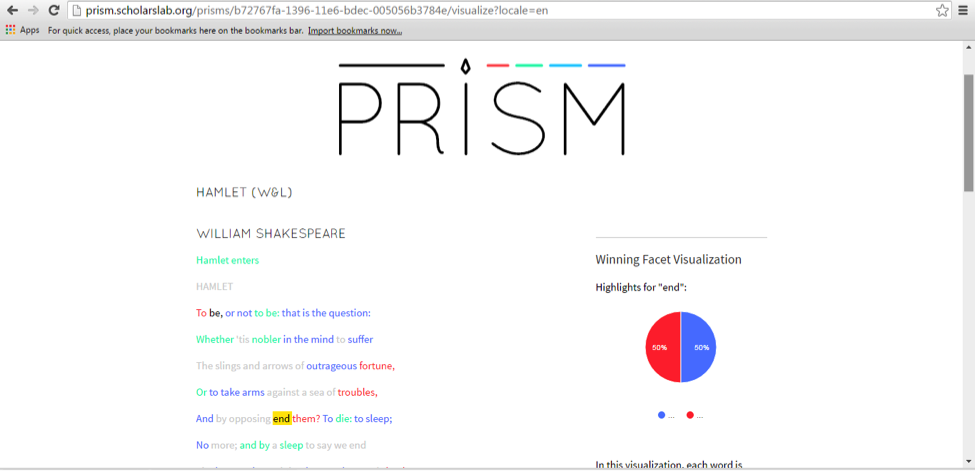

Throughout the whole monologue, “die” and “death” continued to appear as words where students thought some kind of movement or position change should occur, but we couldn’t agree as to what that movement should be:

I have no definitive way to explain this: only a director’s hunch that there’s some sort of affective energy around the word and concept of death that we associate with anxiety that incites us to movement—we (or at least most of us) do not want to be still when facing death. Part of my future work is figuring out how to interpret these results.

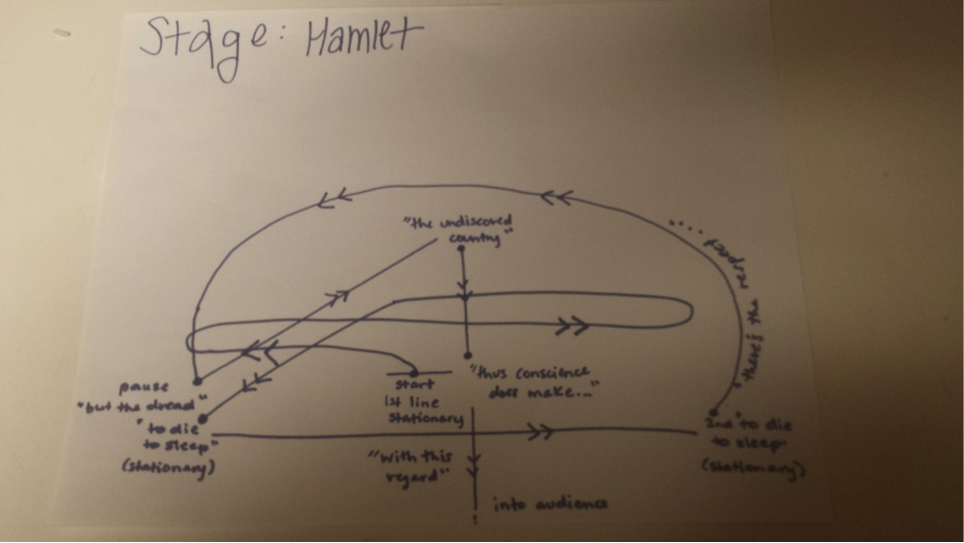

The other part of the activity—the drawings of Hamlet’s path—are much harder to read. Most drawings started Hamlet out on the center of the stage, not accounting for the first bit of text printed in the monologue directing that “Hamlet enters.” To me, this suggests some kind of connection between what we know about Hamlet, the role of this speech in the play, and center stage—we know Hamlet is the central figure and associate this important monologue with the center stage. But aside from that, the patterns varied. Most were well-balanced with Hamlet spending time on both sides of the stage (my mentors would be proud that both sides of the audience would get an equally good view of the actor). Some incorporated gestures or moments of intentional stillness. Many contained loops. Professor Pickett explained that she chose to do this in her drawing because of how she views the speech as rhetorically winding and wanted to create a movement pattern that reflected her reading.

Several of the students actually marked words on their drawings as well connecting the text directly to their movement patterns:

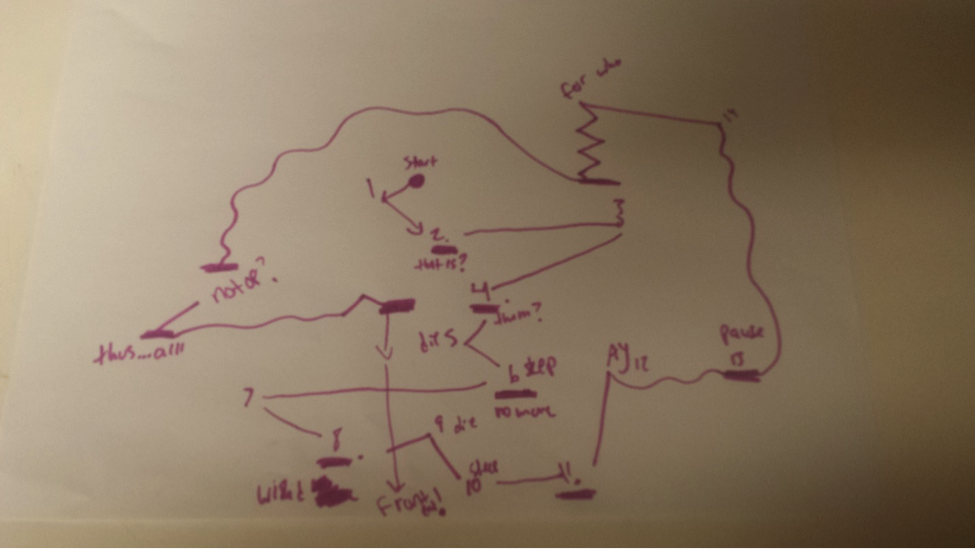

Some used no text at all and focused on the shape of Hamlet’s movements:

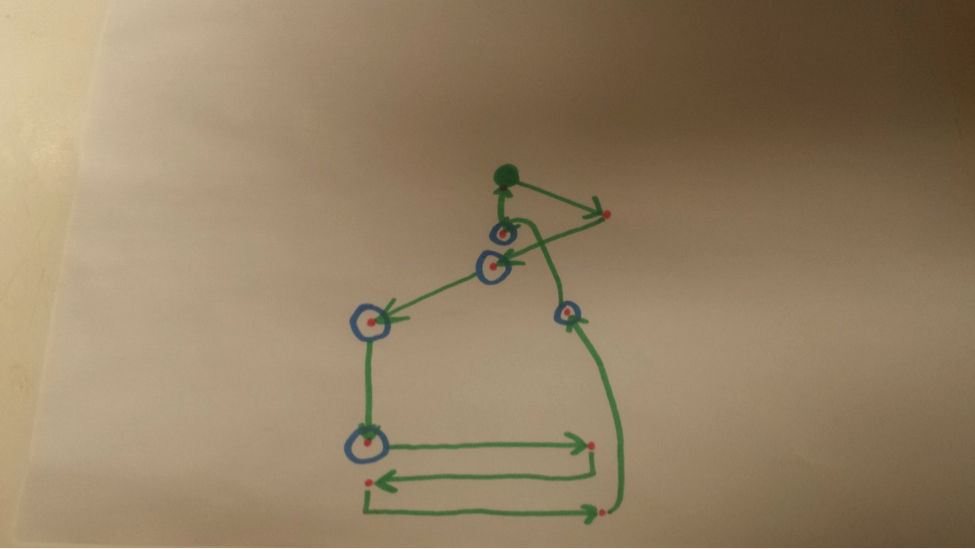

And here’s one that was purposely playing with Hamlet’s winding rhetoric:

So how do we make meaning out of all of this data?

I’m in the process (the slow, painful process) of developing a tool (or likely, a set of tools) to help students visualize the connection between play text and movement patterns. By considering the way language suggests movement will, I hope, allow for a richer consideration of the formal stylistics of particular plays, but also in the long run create corpus of data on the way people see theatre texts. I’m interested in what new areas of inquiry open up if I can use a digital tool to process many blocking patterns of the same scene (i.e. perform a kind of distant reading on the movement patterns that I had the students create). At the least, we can get students to think more deeply about the way that the dramatic text is a living document brought to life, challenged, and enriched by a consideration of the ways its interacts with the body, and embodiment.

This is important work for me both as a literary scholar and a theater director because of the reciprocal relationship between movement and interpretation. The director interprets the text to find places to block movement, and then the audience uses those movements to interpret certain moments on stage. Thinking about the relationship between movement and interpretation helps us to counter the belief that the playwright alone fixes the meaning of his or her “original text” and to recognize the larger networks of people, practices, traditions, and texts that make theater mean something.

-

Broude, Roland. Performance and the Socialized Text. Textual Cultures: Texts, Contexts, Interpretation, Volume 6, Number 2, 2011, 24.

-

Ibid. 25.

-

Phelan, Peggy. Unmarked : The Politics of Performance. London ; Routledge, 1993.

-

It’s entirely worth noting that there should be a lively debate about if there are elements of performance that should not be recorded or analyzed as well. Is the kind of work we’re doing creating a richer context for talking about performances, or are we violently decontextualizing aspects of performance that can’t be understood without the full (but sadly unrecoverable) picture? (Many thanks to Purdom Lindblad for first asking me a version of this question!)

-

I was made aware of this interesting work in dance through sitting in on “The Art of Dance” taught by Kim Brooks Mata in the summer of 2015.