I was recently invited to give a guest lecture in Caleb Dance’s Classics Course (“Blasts from the Classical Past: In Consideration of the Ancient Canon”) at Washington and Lee University as part of their Mellon Foundation Grant for Digital Humanities, which provides support for research, workshops, guest lectures, and the general development of Digital Humanities initiatives. As a contemporary Latin American scholar, who works on Jorge Luis Borges and publishing history, I was, at first, quite daunted by the task of teaching about classical canons and antiquity. Lucky for me (and the students), I was asked to work through possible avenues of investigation for their final project, “Book Biographies,” that required students to add their own text to the class’s “canon” and justify their selection with quantitative and visual data. More specifically, Caleb asked me to present students with a series of approaches for the project, including any necessary platforms and databases, and also touch on some potential problems that might arise in the process.

Before diving into a discussion of the digital tools for the day, I wanted to pause and parse out what exactly a “bibliographical biography” might be. Or rather, what students understood as “bibliographical” or a “bibliography” more generally. The entire class immediately defined the term to mean a list of works cited and used for research (i.e. enumerative bibliography). I then added to their definition by introducing the concepts of descriptive, analytical, and textual bibliography. We spent the most time walking through descriptive bibliography, or the physical descriptive of books as objects, because I felt that an understanding of this branch of bibliography would best serve students in thinking about the physical data necessary for their projects.

I devoted the remainder of the class to presenting students with two avenues of investigation for their digital humanities projects. For fear of selecting a classical work that another student might have already chosen for his/her own project, I used Jorge Luis Borges’s Ficciones (1944) as my example text to add to their class “canon.”

First, drawing on my own current digital project, I introduced students to different modes of visualizing data with digital tools. For starters, I asked students what types of questions they might ask their chosen books to gather the necessary data to populate a map or visualizing tool. Together, we formed a list that included the work’s printing history, cost, copies produced, places of publication, languages of publication, and circulation, which would all help students to answer the central question of why their book should be added to the class’s “canon.” Moreover, I continually emphasized the need to accumulate as much physical data as possible about their work, and keep this information in an easily readable format (such as an excel spreadsheet).

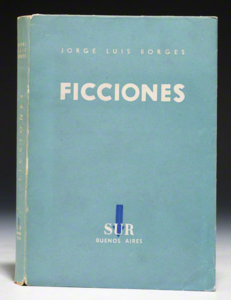

Next, I showed them a demo project I created with an annotated Google map, which plotted the locations of archival materials, such as manuscripts and correspondence, in green and translations of Ficciones in different languages in yellow. As a class, we added new plot points to track the circulation of Ficciones in libraries in the United States with data we quickly acquired from WorldCat in purple:

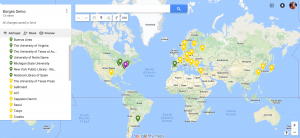

After we mapped out several locations and entered detailed metadata for each point, I wanted to show students several examples of more advanced data visualization projects. My hope was that as these students explored and experimented with their first digital humanities projects, they would be inspired to work with more complex platforms and programs for future projects. Given my own training in the UVA Scholars’ Lab, their unique program Neatline was the most logical place to turn. In particular, I walked the students through a demo of the project, “Mapping the Catalogue of Ships,” which relies on data gathered from the second book of the Iliad to map the physical route discussed based on the locations named, which seemed most appropriate for a Classics course:

While platforms and programs for data visualization allowed the students to see the immediate impact of their selected text in terms of its production and circulation, I wanted to also push them to think about ways to represent the links, connections, and relations between certain authors and works across time and space. For starters, I asked students to think about how many works have been written about their selected texts (in terms of literary references, allusions, critical studies, or even parodies). I then showed them DBPEDIA, which extracts data and datasets from Wikipedia pages for further analysis. Looking to the page dedicated to Jorge Luis Borges, I scrolled to the section of writers that are influenced by him:

Thinking about the various names on this list, and the potential writers that might populate the lists for their own selected writers, allowed students to see the possible outcomes of analyzing social networks of impact. I told students that this type of data was not limited to people and could be expanded to think about various historical, social, or even political movements. After discussing several possible ways to gather data about the social networks related to their own texts, I showed the students a few examples of how their data might visually manifest itself, drawing on sample screenshots from Cytoscape, a platform which helps create complex network visualizations:

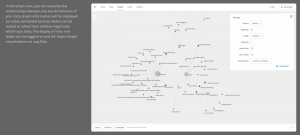

Walking through a few visual examples of network analysis with digital platforms got students really excited for their own projects and their potential outcomes. I then introduced students to Palladio, which is one specific tool engineered by Stanford Digital Humanities for their “Mapping the Republic of Letters” that they might consider using for their own projects. One of the most intriguing aspects of this tool is the ways in which you can manipulate your data. More specifically, as we saw with the sample dataset, you are able to visualize your information in the form of a map, a graph, a table, or through a photo gallery of the players involved:

This variety in format was particularly promising for students that hoped to present their projects in diverse ways and draw on both visualization and social network tools.

Even though we experienced some connectivity issues due to a campus-wide network outage, students were able to see the benefits of using digital humanities approaches for their own projects while also getting a feel for a few of these tools with hands-on tutorials. Moreover, instead of panicking about sites and videos that wouldn’t load for the students, I stepped back and saw these connection problems as a teaching moment. In particular, I embraced the slow internet speeds as a catalyst for reflecting on minimal computing and questions of access in certain parts of the world, such as Latin America. In turn, I encouraged the students to think critically about their projected audiences and how they hoped to not only present their ideas digitally, but also how they hoped to preserve them and make them accessible to a wide range of people.

As a whole I am eternally grateful to Washington and Lee and Caleb Dance for this opportunity to share some of my favorite digital humanities tools, tips, and tricks with undergraduate students and introduce them to software and platforms that can make many of their imagined projects a reality. With each new tool we discussed, I was overjoyed to see students feverishly writing notes and having “Aha!” moments about their unique projects. Much of my DH fellowship year in the Scholars’ Lab has been about exploration and experimentation that tends to end in failure and a return to the drawing board, but, in the process, I’ve learned an incredible amount and had my own personal “Aha!” moments. Successfully being able to teach these students about data visualization and social network analysis was, quite possibly, the biggest “Aha!” moment of my DH fellowship thus far and a real turning point in my career as a digital humanities teacher-scholar.